UnBias Facilitator Booklet

July 3, 2019 by Giles Lane · Comments Off on UnBias Facilitator Booklet

Our colleagues, Helen Creswick and Liz Dowthwaite, at Horizon Digital Economy Institute (University of Nottingham) have recently produced a new booklet for facilitators to accompany the UnBias Fairness Toolkit.

The booklet is the result of an Impact Study grant to run a series of workshops with people of different ages and to co-devise games and activities using the Awareness Cards. It also contains further advice and feedback for facilitators and other running workshops using the Toolkit, to guide them to what works best with different groups.

Download PDF versions to print out and make up

City of Refuge Toolkit

May 10, 2019 by Giles Lane · Comments Off on City of Refuge Toolkit

This is a co-creative and participatory toolkit of relevance to researchers, civil society and institutions working with newcomers, migrants, refugees and those supporting them (citizen actors and organisations).

The City of Refuge Toolkit aims to explore the needs these actors have: such as the resources they need, and the obstacles they face when they try to build inclusive, safe and equitable local and national communities and spaces. The toolkit brings people together to discuss and share their experiences, to build connections and find common ground. It asks participants to identify what an ideal City of Refuge would need to be a reality (the ‘ideal’ city of refuge could be adopted from neighbourhood-level to national level).

The toolkit contains:

- Individual Task Sheets

- Group/collaborative Work Sheets

- A Workshop Facilitation guide for working with refugees/newcomers

- A Workshop Facilitation guide for working with citizen actors

- A Materials Guide suggesting icons and images for stickers

It is available in four languages – Arabic, English, German and Greek.

The toolkit has been devised and created by Giles Lane, with Myria Georgiou, Deena S Dajani, Kristina Kolbe & Vivi Theodoropoulou.

Download the Toolkit Here (Zenodo) | Alternative Download

About

The toolkit has been developed for the study of the city of refuge and to understand how cities are shaped through migration as spaces of hospitality, collaboration but also of exclusions and restricted rights. The tool can be used in different contexts and spaces – from neighbourhoods to cities and to countries, depending on users’ particular focus. The principle remains the same: to co-create knowledge with those directly involved in identifying what makes (and/or hinders) inclusive and diverse spaces of belonging in the context of migration.

The methodological approach integrates and promotes the principle of co-creative knowledge production with the people involved in processes of migration, either as those moving or as those receiving them. More particularly, the toolkit invites participants in cities (also neighbourhoods and countries) at the aftermath of (forced) migration to record their own understanding of needs, resources and obstacles that make hospitable and inclusive spaces of belonging. It comprises nonlinear tools for producing collective knowledge and capacity among those affected by migration to identify needs, resources and obstacles, especially in their attempt to build collective projects and resist exclusions from rights and resources on the basis of nationality and origin.

The toolkit particularly challenges the linearity of narratives that have been privileged in representations of migrant and refugee voices, which are often narrowly defined through either “the refugee as a victim” or “migrants as assets for the economy”. Furthermore, the integration of visual tools in the toolkit aims to integrate participants’ diversity in terms of gender, linguistic and literacy skills. The different tropes used in the toolkit invite participants to work collectively and nonlinearly by writing, drawing and using stickers; in this way, the toolkit aims to tackle hierarchies among research participants, which lineal and fully narrational methods can reproduce.

Translations

Arabic – Dr Deena S Dajani

German – Kristina Kolbe

Greek – Dr Vivi Theodoropoulou

The City of Refuge Toolkit is published by Proboscis, and is an output of the “Resilient Communities, ResilientCities: digital makings of the city of refuge” project – funded through the LSE’s Institute of Global Affairs (IGA) as part of the Rockefeller Resilience Programme.

It is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International.

UnBias Fairness Toolkit

September 7, 2018 by Giles Lane · Comments Off on UnBias Fairness Toolkit

The UnBias Fairness Toolkit is now available to download and use. It aims to promote awareness and to stimulate a public civic dialogue about algorithms, trust, bias and fairness. In particular, on how algorithms shape online experiences, influencing our everyday lives, and to reflect on how we want our future internet to be fair and free for all.

The tools not only encourage critical thinking, but civic thinking – supporting a more collective approach to imagining the future as a contrast to the individual atomising effect that such technologies often cause. The toolkit has been developed by Giles Lane, with illustrations by Alice Angus and Exercises devised by Alex Murdoch; alongside contributions from the UnBias team members and the input of young people and stakeholders.

The toolkit contains the following elements:

- Handbook

- Awareness Cards

- TrustScape

- MetaMap

- Value Perception Worksheets

All components of Toolkit are freely available to download and print under Creative Commons license (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0).

Download the complete UnBias Fairness Toolkit (zip archive 18Mb)

TREsPASS Exploring Risk

December 2, 2016 by Giles Lane · Comments Off on TREsPASS Exploring Risk

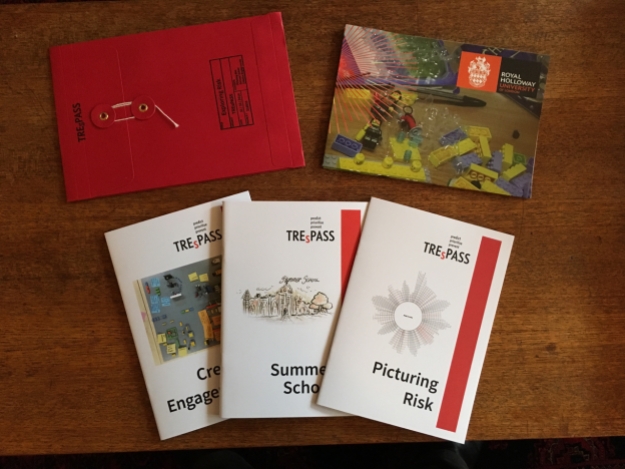

This Autumn Giles has been working with Professor Lizzie Coles-Kemp and her team in the Information Security Group at Royal Holloway University of London to produce a publication as a deliverable for their part of the TREsPASS project.

TREsPASS : Technology-supported Risk Estimation by Predictive Assessment of Socio-technical Security was a 4 year European Commission funded project spanning many countries and partners. Lizzie’s team were engaged in developing a “creative security engagement” process, using paper prototyping and tools such as Lego to articulate a user-centred approach to understanding risk scenarios from multiple perspectives. The three books and the poster which comprise TREsPASS: Exploring Risk, describe this process in context with the visualisation techniques developed by other partners, as well as a visual record of the presentations given by colleagues and partners at a Summer School held at Royal Holloway during summer 2016.

The publication has been produced in an edition of 400, but all 3 books included in the package are also available to read online via bookleteer, or to download, print out and hand-make:

Exploring Risk collection on bookleteer:

We are now starting a follow on project to develop a creative security engagement toolkit – with case studies, practical activities and templates – which will be released in early 2017.

Reite Village Online Library

September 21, 2015 by Giles Lane · 4 Comments

This website has been created as an online library of TKRN notebooks made by the villagers of Reite and its neighbours in Papua New Guinea’s Madang Province. These books were created during a field trip in March 2015 and we hope to add many more in the future. We aim to transfer management of the site to the villagers themselves in due course, so that they can continue growing the library for future generations. As 4G mobile internet service penetrates into the jungle where they live and more local people own smartphones and connected devices, this is an increasingly likely possibility.

Mixing the physical and digital in this way means that traditional knowledge and customs may be preserved and transmitted forwards by embracing some of the changes that industrialisation and urbanisation bring to traditional rural communities. By working alongside the existing relationships of knowledge exchange it offers new opportunities for inter-generational collaboration on self-documentation of stories, experiences, history and practical knowledge of working with and sustaining the local ecology and environment.

The site itself is extremely simple and uses only free services: a free WordPress.com blog as the primary interface for organising and sharing the books; and a free Dropbox account as the primary repository of the PDF files of the scanned books. It is a key component in our TKRN Toolkit, and closes the loop in our use of hybrid digital and physical tools and techniques.

The villagers themselves developed their own categories and taxonomies for cataloguing the books, which have all been tagged accordingly. The books are thus searcheable by title, author and subject(s). Many of the books include an author photo on the cover page; a thumbnail image of the scanned book was included in each post, and a blog theme chosen that presents the main page as a mosaic of images from the posts. For communities with highly varied literacies, it also enables visual recognition both of the author’s faces, and in many cases their handwriting or drawing style.

Magna Carta 800 Set

May 26, 2015 by Giles Lane · 6 Comments

June 2015 is the 800th anniversary of the signing of the Magna Carta – considered by many to be the keystone to Britain’s constitutional and democracy. Over the past six months I have been publishing a series of books – 6 in all – to celebrate the Magna Carta. Each book contains several texts from across the centuries that have been inspired by the Magna Carta: from the English Civil War era, to the French and American Bills of Rights in the late 1700s, the Chartists of the 1830s though to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, Charter88 and the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union of 2000. The final book in series contains Henry I’s Charter of Liberties (1100) on which the Magna Carta itself is based, the original 1215 Magna Carta and the Charter of the Forests of 1217.

What the series shows is a lineage stretching back to Saxon times of the struggle to assert and protect the inherent rights and dignities of ordinary people against the attempts by the wealthy and powerful to control and corral resources, assets and power for themselves, at the expense of everyone else.

These books have all been distributed as part of bookleteer‘s monthly subscription service, the Periodical, with the final book being distributed in June 2015. I have saved 40 copies of each which have been bound together with red satin ribbon in a special edition, which are now available to pre-order from our online store.

Each set costs £20 plus postage and packing: buy your’s here.

View the whole collection here – free to read online or download, print out and make up yourself.

Soho Memoirs Set

May 21, 2015 by Giles Lane · 13 Comments

Last year we collaborated with The Museum of Soho to publish three memoirs by Soho residents from their archives. Each is a poignant recollection of Soho’s yesteryear, of lives lived and worked there. The books were originally distributed as part of bookleteer‘s monthly subscription service, the Periodical, and at a special MoSoho event host by the House of St Barnabas. We’ve put a small number aside and created a special edition of 32, each set wrapped in traditional brown paper reminiscent of a naughtier age, when Soho was a byword for difference and danger.

The sets cost £20 each plus postage & packing. Visit our online store and buy your’s here.

Visualise: Making Art in Context

January 20, 2014 by Giles Lane · 3 Comments

Anglia Ruskin University has published a book, edited by Bronac Ferran, reflecting on the Visualise public art programme. We have contributed a short piece describing our Lifestreams collaboration with Philips Research.

Visualise: Making Art in Context

Published by Anglia Ruskin University

Edited by Bronac Ferran

Designed by Giulia Garbin

ISBN: 978-0-9565608-6-5

Published 28th November 2013

Copies can be ordered from : Pam Duncan, Bibliographic Services Manager, University Library, Anglia Ruskin University

The book brings together essays by artists featured in the Visualise public art programme, which took place from Autumn 2011-Summer 2012 across Cambridge, managed by Futurecity with guest curator Bronac Ferran. It includes reflections on the development of the programme by Professor Chris Owen Head of Cambridge School of Art and from Andy Robinson of Futurecity on the role artists can play in our cities ecology and contested public realm. Among the essays are newly commissioned pieces relating to poetry, composition, music, code, language and place by Liliane Lijn, Eduardo Kac, Tom Hall, Alan Sutcliffe and Ernest Edmonds as well as interviews with Duncan Speakman and William Latham, reflections on two art and industry collaborations by Bettina Furnee and Dylan Banarse, and Giles Lane of Proboscis and David Walker of Philips Research and a previously unpublished holograph by Gustav Metzger.

About Visualise: Making Art in Context

From tales of a transgenic green bunny to a singing painting, from computer-generated lifecharms to a soundwalk at dusk through Cambridge’s streets, parks and arcades, this publication conveys some of the myriad happenings which characterised Visualise; a programme of public art, curated for Anglia Ruskin University in 2012. Funded by the University from Percent for Art sources, Visualise brought new life to hard streets, providing opportunities for public engagement through challenging visual art and sound installations, temporary events and exhibitions. It connected in direct and indirect ways to perceptions of Cambridge as context and site of scientific discovery and technological inventiveness. The book weaves the history of Cambridge School of Art and the Ruskin Gallery (the place where Syd Barrett of Pink Floyd played his first gig and Gustav Metzger, renowned founder of auto-destructive art, had his first arts education before the end of the Second World War) with today’s digital developments. A series of newly commissioned essays provide intriguingly personal insight into how world-leading international and local artists create lasting ‘mark and meaning’ (Eduardo Kac) working in contexts of historical time as well as in physical space.

StoryMaker PlayCubes

November 16, 2013 by Giles Lane · 4 Comments

StoryMaker is a set of 9 playcubes (1 of 3 sets from Outside The Box) that incite the telling of fantastical tales. Roll the three control cubes to decide how to tell your story, what kind of story it should be and where to set it. Then use the six word cubes as your cue to invent a story on the spot. Each set comes flatpacked with a PlayGuide booklet. You can browse all the cubes and the play guide on bookleteer.

Make up stories on your own or with friends. Challenge your storymaking skills with the Genre, Context and Method cubes to suggest what type of story you can tell, what time or place it is set in and how you’re going to tell it. Use the Word cubes to make the game even more fun: choose one set of words to tell you story with, or combine different sets to make up longer stories or more complex games.

Earlier this year we printed up a small edition of the StoryMaker PlayCubes which are now available to purchase. If you’d like a set then please order below or visit our web store for other options.

|

StoryMaker PlayCubes Set

9 PlayCubes + PlayGuide Booklet |

||

|

United Kingdom

|

European Union

|

USA/Rest of the World

|

|

£25

(inc VAT & p+p) |

£30

(inc VAT &p+p) |

£35

(inc p+p) |

|

use PayPal below

|

use PayPal below

|

|

|

Pay with Paypal

|

||

PlayCubes : kickstarting the next stage

October 29, 2013 by Giles Lane · 1 Comment

Three years ago, not long after Mandy Tang started at Proboscis, we came up with an idea to use the StoryCubes and bookleteer to inspire people to play and invent their own games. We were inspired ourselves by the Love Outdoor Play campaign, which aims to encourage children, and their parents, to play outside more. Over about six months Mandy developed Outside The Box as a side-project within the studio, devising the three games with help from the team and illustrating all the resulting cubes. We frequently got together to test out the game ideas, as well as with friends and eventually with a group of children on a YMCA play scheme. But as the studio got stuck into several large projects, we didn’t get round to completing the whole package until recently.

The result is Outside The Box – a “game engine for your imagination” – designed to inspire you to improvise and play your own games on your own or with others, indoors or outside. It’s made up of 27 cubes, 3 layers of 9 cubes, each layer being a distinct game : Animal Match, Mission Improbable and StoryMaker. Outside The Box has no rules, nothing to win or lose, the cubes simply provide a framework for you to imagine and make up your own games. You can browse through the whole OTB collection of cubes and books on bookleteer, to download and make up at home.

However, 27 large PlayCubes and 7 books is a lot to make yourself, so we’re now planning to manufacture a “first edition” to get them into people’s hands to find out what they do with them. To achieve this we’re running a kickstarter campaign to raise funds – support the project to get your own set in time for Christmas or choose other rewards.

- Mission Improbable

- StoryMaker

- Animal Match

Animal Match starts out as a puzzle – match up the animal halves to complete the pattern. From there you can make it much more fun : mix the cubes up to invent strange creatures; what would you call them? What would they sound like? How might they move?

Mission Improbable is for role-playing. There are 6 characters: Adventurer, Detective, Scientist, Spy, Storyteller and Superhero, each with 9 tasks. Use them to invent your own games, record your successes in the mission log books or take it to another level by designing your own costumes and props.

StoryMaker incites the telling of fantastical tales : Roll the 3 control cubes to decide how to tell your story, what kind it should be and where to set it. Then use the word cubes as your cue to invent a story on the spot.

Hidden Families publication

February 27, 2013 by aliceangus · 2 Comments

We have just finished putting together a new publication for the report on Families Disconnected by Prison, of which the Hidden Families project was one part. The project is led by Lizzie Coles-Kemp from the Information Security Group at Royal Holloway University of London and is going to be on show at the AHRC Connected Communities Showcase on the 12 March.

Field Work and the Periodical

September 26, 2012 by Giles Lane · 1 Comment

Publishing remains at the heart of Proboscis. We began 18 years ago with COIL journal of the moving image and followed this with many series of Diffusion eBooks. Since 1994, we have commissioned and published works by hundreds of different people in many formats.

Our latest publishing venture, the Periodical, aims to re-imagine publishing as public authoring – a phrase we’ve been using for over 10 years to describe the process by which people actively make and share what they value – knowledge, skills, experiences, observations – those things we characterise as Public Goods. Based on bookleteer, the Periodical is a way for people to participate in publishing as well as reading – in addition to receiving a printed eBook (sometimes more than just one) by post each month subscribers are encouraged to use bookleteer to make and share their own publications, which may then be chosen to be printed and posted out for a future issue.

Our first project being developed as part of this venture is Field Work : subscribers will be sent a custom eNotebook to use as a sketch and note book for a project of their own. Once they’ve filled it in they can return it to us to be digitised and shared on bookleteer. Several times a year we will select and print someone’s Field Work eNotebook to be sent out as part of a monthly issue of the Periodical.

Why are we doing this? We’ve long used the Diffusion eBook format to make custom notebooks for our projects and digitised them as part of our shareables concept. We think that such new possibilities of sharing our creative and research processes with others is a key strength of what these hybrid digital/physical technologies offer. Creating a vehicle, via the Periodical, for others to take part in an emergent and evolving conversation about how and why we do what we do seems like a natural step forward. If you’d like to take part, subscribe here.

We Are All Food Critics – The Reviews

July 6, 2012 by Giles Lane · 1 Comment

One of the most fun things we’ve done this year has to be the little project we ran as part of the Soho Food Feast : helping some of the children of Soho Parish Primary School produce their own reviews of the amazing foods on offer in specially designed eNotebooks. The children would choose something from one of the many stalls, bring it to be photographed and a Polaroid PoGo photo sticker printed out an stuck into one of the eNotebooks, then they’d write about what the dish looked, smelt, felt, sounded and tasted like. This idea of doing the reviews through the 5 senses, along with the great introduction, was contributed by Fay Maschler, the restaurant critic of the London Evening Standard and one of the Food Feast committee members.

We’ve now published a compilation of the best reviews which is available via the Diffusion Library as downloadable eBooks and in the bookreader format. We’re also printing a short run edition which will go the children themselves (and a few for the school to sell to raise funds – get one while you can!). Thanks to everyone who took part in this project – the children of Soho Parish and Soho Youth, members of the Food Feast Committee (Anita Coppins, Wendy Cope, Clare Lynch), Rachel Earnshaw (Head Teacher) and the team here : Mandy Tang, Haz Tagiuri & Stefan Kueppers.

ATLAS: Geography, Architecture and Change in an Interdependent World

June 20, 2012 by aliceangus · Comments Off on ATLAS: Geography, Architecture and Change in an Interdependent World

Earlier in the spring I received a copy of ATLAS: Geography Architecture and Change in an Interdependent World (edited by Renata Tyszczuk, Joe Smith, Nigel Clark and Melissa Butcher) a new book published by black dog publishing that brings together architects, artists and geographers to look at global and economic change. It is linked to and grew out of the web project ATLAS: making new maps for an island planet. Many of the contributors to these projects, like me, were part or participated in events or publications arising out of the Interdependence Day (ID) project back in 2006 and the organisers have gone to great lengths to keep those people and ideas together over the years through events, discussions and publications that keep progressing ideas and conversations.

For Atlas I revisited the project In Good Heart; What Is A Farm? (2009) which grew out of the partnership between Dodolab and Proboscis exploring communities, environment and resilience. I has been invited to visit the former Charlottetown Experimental Farm on Prince Edward Island, Canada, by arts organisation Dodolab. The visit, coupled with conversations with people and farmers, historical research into representations of farming, the lore of agriculture, weather, the seasons and the labours of the months, triggered many questions about land, farming and the factors that impact on this most ancient and technologically advanced of trades. The map created for ATLAS was inspired by these questions and the mediaeval illustrations of the Labours of the Months which were some of the first representations of farming and food production. It maps the interconnected stories people told me about what the word farm meant to them; their hopes and fears about food production and the harsh realities for farmers themselves. One of the things that struck me was how many people, who now live in urban places, recalled growing up on farms of visiting their grandparents farms. It impressed on me how swift the move from rural to urban has been for some people. Knowledge about environment has shifted with that move, some knowledge must have been lost and other knowledge is perhaps being created.

Professor Starling’s Thetford-London-Oxford Expedition

June 1, 2012 by hazemtagiuri · 2 Comments

We’ve just published our latest entry in the City As Material series: ‘Professor Starling’s Thetford-London-Oxford Expedition’ – three books documenting the investigative excursions of Professor William Starling and his research team (Lisa Hirmer and Andrew Hunter of DodoLab, Josephine Mills of the University of Lethbridge Art Gallery, Lethbridge artist Leila Armstrong, and Giles Lane and Hazem Tagiuri of Proboscis) during his trip to the United Kingdom in Feburary, where he sought to examine the rapid disappearance of the European Starling in contrast to the continued expansion of its North American cousin.

The first volume, Perquisitions, contains descriptions of the various participants’ thoughts on the expedition and its rationale. Congeries showcases selected items and ideas collected during their travels, and the final volume, Speculations, offers reflections and fantastical musings on the material gathered and testimonies heard.

Purchase a limited edition copy complete with specially printed ribbon here.

(Read the accounts of Thetford, London and Oxford on the blog)

Mapping Perception Redux

March 20, 2012 by Giles Lane · Comments Off on Mapping Perception Redux

Ten years ago, in 2002, we completed a major 5 year collaboration between myself, filmmaker and artist Andrew Kötting and the neurologist Dr Mark Lythgoe. The project, Mapping Perception, had been an extraordinary journey for us exploring the membrane between our perceptions of ability and disability, through the prism of impaired brain function. Andrew’s daughter, Eden, who was born with a congenital syndrome called Joubert’s (which causes the cerebellum to remain underdeveloped) was both the inspiration for this project and its heart. For the project we produced a major site-specific installation, a 35mm 37 minute film and a publication and CD-Rom.

On Monday 19th March the BFI is to release a new DVD (which includes the Mapping Perception film as a special feature) of Andrew’s latest film, This Our Still Life – a portrait of Eden now grown into a young woman. We’re really excited that MP is present on the DVD as it will mean a whole new audience for the work and are teaming up with the BFI to provide 50 free copies of the Mapping Perception Book & CD-Rom for people ordering the DVD (more details / link to come).

COIL journal – last few sets special offer

February 8, 2012 by Giles Lane · Comments Off on COIL journal – last few sets special offer

Over the past few weeks we’ve been re-arranging the studio to create new work spaces (such as the fabbing corner for the Public Goods Lab) and have been sifting through our archive to make space. We’ve been culling the number of archive copies we keep of various publications, especially of our older works which means we can release them for sale. As such, we are now making the last 15 complete sets of COIL journal of the moving image available for sale at the super low price of £25 plus shipping.

COIL journal was a 10 issue part-work commissioning new writing, critique as well as artists projects about experimental film, video and the emerging electronic/digital art field between 1995 and 2000. Over 130 filmmakers, artists, writers, critics and others were commissioned for the series – each one invited to make their own intervention in the journal about moving image culture (rather than respond to editorial themes). The journal deliberately eschewed featuring the then-current ‘YBA’ group of artists, focusing on a mix of younger emerging talent with older mid-career artists – many of whom we’re less visible at the time. COIL is thus a snapshot of a fecund period during which the shift from analogue to digital technologies gathered pace and the changes in creative practices associated with these became more pronounced.

Material Conditions Limited Edition Set

December 15, 2011 by hazemtagiuri · 4 Comments

Material Conditions is a new series of eBooks created with bookleteer, asking professional creative practitioners to reflect on what the material conditions for their own practice are, especially now in relation to the climate of change and uncertainty brought about by the recession and public sector cuts.

It aims to explore what it means and takes to be a professional creative practitioner – from the personal to the social and political. How and why do people persist in pursuing such careers? How do they organise their everyday lives to support their practice? What kind of social, political, economic and cultural conditions are necessary to keep being creative? What are the bedrocks of inspiration that enable people to continue piloting their meandering courses through contemporary society and culture?

The first set of 8 commissioned eBooks, in a limited edition run of 50 copies printed via our Short Run Printing Service and bound with handmade wrappers, are as follows:

A Conversation Between Trees by Active Ingredient

The Show by Desperate Optimists

Making Do by Jane Prophet

Something More Than Just Survival by Janet Owen Driggs & Jules Rochielle

Remix Reconvex Reconvexo by Karla Brunet

He Who Sleeps Dines by London Fieldworks

Reflections on the city from a post-flaneur by Ruth Maclennan

Knowing Where You Are by Sarah Butler

Copies are available to order below.

The books are also available online as bookreader versions, as well as downloadable PDFs for readers to assemble into handmade booklets themselves, hosted on our archive of publications Diffusion – view and download the series here.

Material Conditions is part of Proboscis’ Public Goods programme – seeking to create a library of responses to these urgent questions that can inspire others in the process of developing their own everyday practices of creativity; that can guide those seeking meaning for their choices; that can set out positions for action around which people can rally.

Material Conditions 1

November 29, 2011 by Giles Lane · 2 Comments

On December 15th 2011 we will be launching a new series of Diffusion commissions called Material Conditions. This series asks professional creative practitioners to reflect on what the material conditions for their own practice are, especially now in relation to the climate of change and uncertainty brought about by the recession and public sector cuts.

The contributors are : Active Ingredient (Rachel Jacobs et al); Karla Brunet; Sarah Butler, Desperate Optimists (Jo Lawlor & Christine Molloy); London Fieldworks (Bruce Gilchrist & Jo Joelson); Ruth Maclennan; Jules Rochielle & Janet Owen Driggs; and Jane Prophet.

The first set of 8 contributions will be published as Diffusion eBooks (made with bookleteer) and available as downloadable PDFs for handmade books, online via bookreader versions and in a limited edition (50) of professionally printed and bound copies which will be available for sale (at £20 per set plus P&P).

Material Conditions is part of Proboscis’ Public Goods programme – seeking to create a library of responses to these urgent questions that can inspire others in the process of developing their own everyday practices of creativity; that can guide those seeking meaning for their choices; that can set out positions for action around which people can rally.

Drawing for Agencies of Engagement

November 21, 2011 by mandytang · Comments Off on Drawing for Agencies of Engagement

Recently the Proboscis team have been working with the Centre for Applied Research in Educational Technologies (CARET) and Crucible at the University of Cambridge on a collaborative research project. As the artist for this project, my responsibility ranged from creating visual notations during discussion and brainstorming sessions to illustrating the outcomes of the teams’ reflections in the form of insights and observations. My work was incorporated into a set of books known as Agencies of Engagement.

Each book required a different approach to create a series of illustrations, to accompany the written narrative.

The very first being, visual notation. I used this in the early stages of the project to capture the different ideas discussed during brainstorming sessions. The challenge here was that the discussion was live, it was vital to listen carefully; picking out words to sketch as fast as possible and trying not to fall behind. The idea to this approach was to allow others to see the dialogue visually, the illustrations represented words, topics and how it connected with each other.

The next series of illustrations was aimed to capture the moment of an activity, it was placed in the book describing the project’s progress (Project Account). The sketches consisted of members taking part in a workshop, it was illustrated by using the photographs taken during the session as the foundation and creating a detailed line drawing on top to accompany the detailed nature of the Project Account book.

The most challenging of them all was for the book, Drawing Insight, this book consisted of the teams’ insights and observations. The illustrations were quite conceptual, and although accompanied with captions the representations of these illustrations needed to be obvious to the reader. Thus being a very iterative process and required a lot of patience, I would often talk to the team to define the meaning behind captions to develop sketches to reflect it and then after a thorough review sketches would be tweaked, polished and re-polished until we felt that they had captured the right feeling.

The illustrations used in the Method Stack book, took on the same principle as the Project Account but with less detail. The aim to this approach was to simply suggest and spark ideas in relation to the thorough explanation to each engagement method, by keeping it as simple line drawings it becomes easier for the reader to fill in the blanks with their own creativity.

Finally, Catalysing Agency had a combination of both visual notations from an audio recording from the Catalyst Reflection Meeting and conceptual illustrations like those used in Drawing Insight.

This was my first research project with Proboscis, it was a very intricate one and no doubt the experience I gained from this will be invaluable. Learning about the different methods of engaging with participants of this project and putting them into practice, and deciphering complex findings into a visual to give an insight to others were the main lessons learnt throughout this project, it emphasised the importance of dialogue and communication.

Agencies of Engagement has enabled me to explore and refine my skills in terms of the different approaches to creative thinking. It wasn’t as simple as sketch what you see; there were multiple layers of things to consider – meanings, perception and how the illustrations were to be perceived. Not only was I able to hone my artistic skills in my comfort zone of conceptual illustrations, I was able to explore new techniques such as visual notations in a live situation and both styles of line art for Project Account and Method Stack.

I’ve received my own copy of the finished publication and am overwhelmed with pride, the team did an amazing job and I look forward to participating in more projects like this.

Agencies of Engagement

November 17, 2011 by Giles Lane · 2 Comments

Agencies of Engagement is a new 4 volume publication created by Proboscis as part of a research collaboration with the Centre for Applied Research in Educational Technology and the Crucible Network at the University of Cambridge. The project explored the nature of groups and group behaviours within the context of the university’s communities and the design of software platforms for collaboration.

The books are designed to act as a creative thinking and doing tool – documenting and sharing the processes, tools, methods, insights, observations and recommendations from the project. They are offered as a ‘public good’ for others to learn from, adopt and adapt.

Download, print out and make up the set for yourself on Diffusion or read the online versions.

Back and Beyond

July 15, 2011 by aliceangus · Comments Off on Back and Beyond

The new Lancashire based publication Back&Beyond, out this week, have published a feature on As It Comes. The team behind this arts, culture and heritage publication have a long-term goal of creating a regular, high quality arts publication for the area. It combines fiction and non-fiction writing together with profiles of local artists, projects and organisations. The publication is created by a group of artists, designers and writers and this first issue is free, if you would like a copy they can be found around Lancaster or contact Back&Beyond directly.

You can also download the entire publication from the Back&Beyond website or the As It Comes spread here.

Looking back on Bookleteer

June 23, 2011 by aliceangus · Comments Off on Looking back on Bookleteer

It is now a year since we launched the short run printing service for Bookleteer our online self publish and print platform. So now seemed like a good time to start a series of posts reflecting on the diverse uses people have found for it. Fredrick Leasge has been doing a series of case studies and interviews over on the Bookleteer Blog with people who have used it. Ive been interested to read how some historical and ethnographic projects that have used this method of publishing for documentation and communication.

Julie Anderson, the Assistant Keeper of Egyptian and Sudanese Antiquities at the British Museum used Bookleteer to create 1000 books in Arabic and English about a 10 year archaeological excavation in Dangeil, Sudan to share the findings with the local community in Sudan.

Following the distribution of the book, teenagers began coming to our door in the village to ask questions about the site / archaeology / their own Sudanese history… connecting with their history as made possible through the booklet. It was astonishing. More surprising was the reaction people had upon receiving a copy. In virtually every single case, they engaged with the Book immediately and began to read it or look through it….The Book has served not only as an educational tool, but has empowered the local community and created a sense of pride and proprietary ownership of the ruins and their history.

Bookleteer was used in the Melanesia Project to record, Porer and Pinbin, indigenous people from Papua New Guinea discussing objects in the British Museum’s ethnographic collection. Bookleteer was used first to create simple notebooks that were printed out on an office printer and handmade. Anthrolologist James Leach used them to note the discussion in both English and Tok Pisin, next to glued in polaroid images, to produce a record that involved “capturing the moment of what we were doing and what we were seeing”.

Once filled in the notebooks were scanned and professionally printed to share with the local community in Papua New Guinea. (who have a subsistence lifestyle without electricity).

“[…] As something to give people, they’re an extremely nice thing. People are very keen. I also took some to an anthropology conference before I went [to Papua New Guinea] and would show them to people and they’d immediately say “Oh, is that for me?” People kind of like them. They’re nice little objects.”

Researcher and community education worker Gillian Cowell has used the books as part of a community project with Greenhill Historical Society:

“I think, for community work, it’s really important that you engage in much more unique and creative and interesting ways as a way of trying to spur some kind of interest and excitement in community work […] The books are such a lovely way for that to actually fit with that kind of notion.”

If you are interested in finding out about how you could use Bookleteer, come along to one of our day long Pitch Up & Publish Workshops or Get Bookleteering short sessions this summer.

In Through A Dark Lens – The Proboscis Effect by Bronac Ferran

April 21, 2011 by admin · Comments Off on In Through A Dark Lens – The Proboscis Effect by Bronac Ferran

IN THROUGH A DARK LENS – THE PROBOSCIS EFFECT

A Critical Text about Proboscis By Bronac Ferran

Creativity and innovation proceed in cycles rather than in some remorselessly forward trajectory. It is only over time that we can see the significance and importance of some projects and initiatives and particularly within the arts and cultural world, there are many different lenses and perspectives which we might take on work which we may wish to call contemporary.

In this text I respond to an invitation by the Proboscis Co-Directors, Alice Angus and Giles Lane to consider their work through the lens of collaboration and partnership. I approached this task aware that often the most critical developments happen below surface, in cyclical and indirect fashion. I was intrigued to explore how far one might consider this conceptually as a counterpoint to the increasingly predominant use of short-term quantitative analysis to assess value within the arts and concerned that such an approach is highly inappropriate for research-led practice (and indeed sometimes also for practice-led research) both of which activities may primarily be focussed on exploring new spaces, opening up dialogues and experimentation in form and media whose value can only become visible over time.

I have long been concerned to argue for value (and in particular symbolic value) of not for profit research-led or research-active creative organisations. John Howkins, a guru of ‘Creative Economy’ thinking, who had indirect influence on the new Labour Government‘s policies in this area from 1997, has recently shifted his focus to the term ‘Creative Ecology’ in which he outlines a more holistic approach to this area. In his book Creative Ecologies – Where Thinking is a Proper Job he argues that “attempts to use ecology to illuminate creativity has hardly begun, beyond using it as a fancy word for context”. In this essay I hope to build some layers onto this observation drawing on the work of Proboscis whose engagement with place, space and locality working with variable types of media provides the context for this text.

Proboscis describes itself as a non-profit artist-led studio “focused on creative innovation and research, socially engaged art practices and transdisciplinary, cross-sector collaboration”. Since its formation in 1994 it has made many ‘journeys through layers’ as is more fully described below. One consistent aspect has been that the work has engaged with numerous different agencies and communities, spanning and bridging private and public domain; always integral to their practice has been the development of publishing and storytelling initiatives using print and networked media processes with a primary concern for combination of image, word and text.

Proboscis was first formed by Giles Lane and Damian Jacques as a partnership to develop COIL journal of the moving image which ran through to issues 9 and 10 launched as a joint issue in December 2000. Alice Angus joined the partnership in 1999 and began leading some significant projects including the seminal Topologies initiative which was formative in terms of what was then known as collaborative arts practice and funded through the Collaborative Arts Unit at Arts Council England where I then worked, interfacing successfully and in a ground-breaking way between contemporary art practice and the Museums, Libraries and Archives services in the UK. The breadth of this project which ran between 1999 and 2000 added many layers to Proboscis and as is noted below, was shaped by an ideology and set of aspirations which were fully admirable and still unfolding now, in a considerably harsher climate in terms of arts and other public funding.

Why Proboscis?

Irish poet Patrick Kavanagh rightly wrote that “naming the thing is the love-act and the pledge”. With the choice of their name the organisation certainly pledged itself to a high degree of engagement with environment and context.

As Wikipedia tells us the word Proboscis was:

First attested in English in 1609 from Latin proboscis, the latinisation of the Greek προβοσκίς (proboskis), [2] which comes from πρό (pro) “forth, forward, before” [3] + βόσκω (bosko), “to feed, to nourish”. [4] [5] The correct Greek plural is proboscides, but in English it is more common to simply add -es, forming proboscises.

& ‘In general it is an elongated appendage from the head of an animal’ and ‘the most common usage is to refer to the tubular feeding and sucking organ of certain invertebrates such as insects (e.g., moths and butterflies) worms (including proboscis worms) and gastropod molluscs.

Seeing Proboscis and its life cycle as a kind of organism is curiously appealing. I am not sure if it is predominantly elephant or butterfly – or even mosquito… perhaps all these things. Or maybe it’s the Proboscis monkey, swinging from tree to tree in the wind.

On initial encounter with their work I had felt immediately the extensive and expansive qualities of the imaginative terrain over which Proboscis sought to roam not least because of the multi-partner/multi-agency nature of the Topologies proposal. Giles himself was making a fascinating bridge between research in academia with strong commercial connections (working as he was part-time developing a publishing imprint in Computer Related Design at the Royal College of Art at time when there was an ongoing research partnership with Paul Allen’s Interval Research) as well as growing Proboscis as an independent arts agency. In terms of how and where and why they proceed in certain directions extending their range of enquiry, engagement and investigation, their presence in various contexts seeming partly intentional, partly collaborative and always based on an underlying agenda that has critical intervention at its core.

It is at perhaps at edges of collision and collusion between public and private spheres, policies and desire, that what I wish to name the Proboscis effect has been most active.

Probing Proboscis

In probing Proboscis over the past twelve months looking closely at their core ethos and expression in various permeations I have sought to do more than simply referencing the collaborations and partnerships with which they have been involved as this narrative is already substantially documented on their very useful website.

What I have sought to do is to try to decipher the underlying systems and motivations that drive the process of development behind the course of Proboscis’s work. In setting out to do this I thought I should also confront and re-evaluate my own set of perceptions and assumptions about their work in order to gain some new understanding from the process of dialogue and interaction that this project has deserved. I have therefore been developing a set of informal ‘dialogues or infusions’ with Giles and with Alice to absorb their current preoccupations and conscious that they work (as I tend to do where possible) in collaborative and reflexive ways. So it has become a critical aspect of doing the text to destabilise my own existing conception of what Proboscis is and, in so doing, I have hopefully begun to understand what they might do next.

It has of course been interesting writing this against a backdrop of Arts Council England’s major review of their regularly funded portfolio. In 2004-05 along with then colleague Tony White we had made a strong and in the end successful pitch for regular funding for the Proboscis team as part of a larger series of arguments relating to the shifting nature of cultural practice, the growth and emergence of interdiscipinarity as an innovation layer and the fact that there were arts development and production agencies (in this case, the Arts Catalyst, onedotzero, Forma Ltd) and some artist-research organisations (like Mongrel… and Proboscis) which were as significant to the emerging arts infrastructure as orchestras and ballet companies were to the established performing arts canon or galleries to local authorities and the defined visual arts. I had felt that it was the right time to make this case to help these often small-scale organisations to get funding for their core costs so that they could avoid having to make countless small project applications which drew on time and energy and also we argued successfully for the benefits of providing a core allocation that would enable these essentially innovation focussed organisations to prepare the ground for their next phase of development through periods of research and development, travel and experimentation that would inevitably result in valuable new work over the course of the following few years. Making this argument in terms of policy criteria of excellence and innovation and in the context of building multiple partnerships with arts investment (as often these agencies were being highly entrepreneurial leveraging many new kinds of partnerships with other sectors nationally and internationally, batting well above their weight) was effective and allowed for growth and adaptation over time.

It was then important we felt to consolidate an emerging sector that was in many ways ahead of the curve in terms of arts policy. One can argue for strategic (and perhaps then) symbolic value by citing the significance of arts organisation x as the key agency for xxx (e.g. disability arts or public art) but at the same time when it comes to interdisciplinary research-based practice it can limit an organisation greatly when it becomes too specifically defined by a primary funder as there to deliver something in particular – ie to be the instrumental infrastructural agency to do something that mirrors a policy… this particularly applies for organisations like Proboscis which exist on opening up challenging and redefining the spaces between categories, fields and form and indeed establishing and activating critical and significant tensions or gaps between arts funded agency and the arts funding agency itself. These significant gaps are often where the best interdisciplinary practice lies – not representing anything but heralding stuff to come, shifts that will eventually mainstream over time.

On the Act of Interpretation and Analysis

My overall sense since being invited in early 2010 to write an essay about their work particularly from the viewpoint of the range and complexity of partnerships they have made and held during the past decade and a half of their existence as an arts organisation, has felt like I have been staring at tracks in the snow, looking at something which is already formed and fully crystallised and not that much needing of further explanation. And in addition to this, in seeking to assemble some kind of overview or extract a narrative that condenses and crystallises anything definitive from their ongoing processes of enquiry I have held a burden of doubt about the ‘realness’ of what I have set out to do – a belief perhaps that ultimately the work that has lain within the Proboscis shadow speaks for itself, that the documentation of their processes has been carried out in an exemplary way that can benefit little from tacked on interpretation, exegesis or explanation.

At the same time, and with a sense of an organisation engaged in an ongoing process of ‘adaptive becoming’, I felt it could be useful to move towards a perspective on Proboscis which allows us to see their work as a whole, holistically I suppose – as opposed to a series of distinct projects, which is how often their work is discussed or perceived. I was hoping to define a pathway or journey through their layers – perhaps move further along the path in the snow. In a text they produced for the Paralelo, Unfolding Narratives in Art, Technology and Environment publication in 2009, they cite Katarina Soukip, writing in the Canadian Journal of Communication:

‘the new Inuktitut term for internet, Ikiaqqivij or ‘travelling through layers’ refers to the concept of the shamen travelling across time and space to find answers’.

For the past decade and a half they have had a central place along with other organisations that may be broadly described as working within the media art or trans-disciplinary circuit in the UK and Europe with a primary role in respect of ‘the ecology of learning’ to use Graham Harwood’s term. In another essay which I wrote in 2010 for LCACE I spoke of their unique and pivotal position in terms of art/technology/academic/commercial networks – one of the reasons they were invited by the Engineering and Physical Science Research Council to become an Independent Research Organisation in 2004 which has been written about in detail – see Sarah Thelwall’s Cultivating Research – where she accounts for how “Proboscis has built its artistic practice around a research approach and in so doing has collaborated with a number of HEIs over the years including the Royal College of Art, London School of Economics, Birkbeck College, Queen Mary University of London and the Institute of Child Health“. Thelwall’s text summarises the range and nature of the Proboscis partnerships inside and outside Higher Education and the economic and other factors influencing their success in gaining Independent Research Organisation status from the EPSRC. She also reflects on the processes of layering I have mentioned above:

‘Proboscis have always developed and maintained a very wide and diverse collection of organisations and individuals they collaborate with. They purposefully bring together organisations as diverse as the Ministry of Justice, Science Museum & Ordnance Survey. This network is built around the delivery of projects but is by no means limited to the parameters and timescales of the projects themselves. It is common to see connections made in one project resurface some years later as what might appear to be a tangential connection to a new piece of work’.

This positioning within an ecosystem of connected and interdependent elements which may combine and recombine over time seems an integral aspect of ‘the Proboscis effect’. This is very much a distinguishing element of their work – a specific way of working, in porous and co-operative ways, engaging with locality and often with habitat.

The advent of Arts Council England funding changes now announced, which have swept through the ecosystem of digital media organisations in this country with desperate disregard for preserving and sustaining knowledge within a still developing sector – reminds us to suggest the importance of finding ways to recycle and re-embed these elements into a broader cultural ecology. In this sense Vilem Flusser’s words about waste come very appropriately to mind:

‘Until quite recently, one was of the opinion that the history of humankind is the process whereby the hand gradually transforms nature into culture. This opinion, this ‘belief in progress’ now has to be abandoned. …the human being is not surrounded by two worlds then, but by three: of nature, of culture and of waste. This waste is becoming ever more interesting…’

Somehow this seems appropriate in many ways to Proboscis preoccupations. They have separated themselves from dependency on ACE life rafts for floating media practices and now have set themselves new agendas, new partnerships and new horizons engaging even more closely with critical social challenges from global technological waste to employment of young people from disadvantaged contexts in London.

The Partnership Domain

As noted above many of the projects which Proboscis have generated and fostered have been formative in terms of exploring and building transformative connections between variable and separate fields, particularly between artistic research, academic research, commercial R&D and the public domain. The projects which they have worked on and generated over the seventeen years of the organisation’s existence have had an exciting range reflecting broader shifts within cultural practice. In addition to conceiving and shaping various projects Proboscis as an arts organisation has defined itself during this time as a vital critical space for understanding the emergent nature of collaborative practices, from research through to the public domain and as an agency through which documentation and discourses around these processes has been facilitated and enabled. What it has also most critically done is to provide a space for documentation and critical reflection on these processes – their significance has partly been to find a way to make the temporal or temporary processes of collaboration stable in terms of existing in accessible documentation over time. As their website now rumbles with tag-clouds and twitter-feeds it continues to grow in an organic fashion, as a responsive and collaborative space enabling expression of differences within an open and common domain.

Why does this matter?

In considering patterns of collaborative arts practices in the past fifteen years, often emergent work has been primarily time-based with documentation of the practices secondary to the event of the work itself. Simultaneously when we speak of interdisciplinarity what is commonly implied is the construction of spaces for dialogue and exchange, for things to be ‘in formation’, contingent, open and process-based.

In viewing the work of Proboscis through the lens of interdisciplinarity and collaboration across different arts and other disciplines over many years and recognising the high level of intention with respect to formation of high profile partnerships which have in a sense redefined ‘the public domain’, one recognises a consistent line of enquiry: the probing of interstices, the construction of new interfaces, the drawing of connecting lines, tracing points of relation through dialogue and through process. The process is never mechanical but somehow organic and collaborative – as traces are made, they may also be erased. Or they may be retained held in the act of publishing, drawing or commissioning critical texts. These traces gain longevity and new emphasis also by means of citation (for example the high degree to which Proboscis’s work has formed part of PhD theses and other types of reports) a fact which may carry little weight in relation to arts funding assessments but may in other important ways (particularly if viewed longitudinally) reveal value, especially intellectual or symbolic value as noted above.

In referencing a latency I am also signalling how in the nature of research based arts practice only by looking at developments over time might one truly realise the value. At times something may be in germination stages lying low in order to succeed but hard if not impossible to measure. These stages are in my mind at least the most important stages and ones most deserving of subsidy.

As noted above and looking now in hindsight at how the life cycle of the organisation we know as Proboscis has evolved we see many layers embedded over time. The projects have moved through moving image, film, locative and other mobile media, software, performance, carnival, workshops in making, storytelling and narrative, diy and open access publishing, photography and psychogeography, art and science, art and health, artists books and libraries, archives and community memory, folk-tales and archaeologies of place, open public data, art-industry, art-ecology and design/co-design and many other things. Within all the projects has been a set of disparate connections – sometimes with other artists, sometimes with scientists,sometimes with companies, sometimes with academia – and often with groups working in similar fields, as part of a set of network connections – producing an identity which is both fixed and process-led.

Somehow in these spaces between specificity and hybridity and tracing and erasing the Proboscis effect adheres.

It is vital to also consider the development of the Proboscis effect or practice within the context of recent intensive shifts with respect to how artists and arts organisations work within the spectrum of a broader creativity often, though not exclusively, technologically related. The most compelling work in this terrain has brought about a fusion of different disciplinary approaches and a combination of themes, fields and metiers into common and uncommon forms. This period of development has brought about also a shift within the nature of culture itself not just towards hybridity but towards open and collaborative works that engage directly with audiences or users transforming their position from user to co-producer, collaborator and joint agent within a process or design.

Proboscis’s work in the early 21st Century radically anticipated this layer which is now fully mainstream – of encouraging social innovation based on participatory processes.

Identity

In terms of how they approach collaborations and partnerships it is perhaps interesting to also consider the internal relationships which inevitably drive and define this kind of organisation. When one considers the identity of Proboscis, we recognise a pattern similar to the other organisations of similar scale and size. Often these organisations are indelibly connected to the personalities of their original founders. At the same time, when it comes to small-scale organisations the intensity of the human relations (the personality and behaviours within the group) often transfers to become the image of the organisation as a whole. Organisations form around and mirror the values and ideas of the people who form them. When people change the organisations inevitably change. But organisations evolve even when they have the same people involved who helped to develop the initial projects. In the case of Proboscis, its work has shifted and developed radically showing the various inputs and influences of the various people who have become involved over the years at project, administrative and consultancy level – yet it has also retained and maintained a consistency that is highly recognisable though perhaps difficult to define. Over many years they have brought in various skilled people to work on diverse projects which has provided an abundant network within which the organisation is situated and which they have in turn helped to generate and facilitate at various points and in various places. The workplace trainees who have been present in the office over the past year have been carrying and bringing a different, more youthful energy into the studio and as their voices grow louder as they are encouraged to express their views online and this has in turn shifted the pattern of perception of how and what Proboscis does. At the very heart though is the deeply creative core relationship of the two Co-Directors whose differing and complementary sensibilities suffuse all aspects of their work.

Garnering the Spaces Between

When it comes to unique organisations that are built on activating and ‘the space between differences’, in exploring commonalities and uncommonalities, in the energies that combine and force apart processes and practices – in other words, interdisciplinarity – it may well be said that change is the only constant and that inherent within the suggested Proboscis effect is the opening up of new relations from investigation of these tensions. I am suggesting this as it seems to me that implicit within any discussion about collaborations and partnerships is a belief system or set of values that informs and entwines with the nature of these connections and that what has partly distinguishes how Proboscis has been working in these interdisciplinary fields has been a set of principles or operating framework which has insisted on autonomy and independence of status within a broader assemblage or set of networks.

‘… But also, the value of dissent needs to be high enough so that dissent is not dismissed. How do you facilitate dissent so that it’s a strong value? Part of the concern in science collaborations is that there is a huge push towards consensus. So the dissent issue becomes very important’.

– Roger Malina

Achieving Effective Process within Asymmetrical Relations

The strength of the process was demonstrated most visibly in the pioneering Urban Tapestries project which Proboscis initiated and ran between 2002 and 2004 and which probably for the first time ever demonstrated the capacity of a small not for profit organisation to draw together a set of large institutional and commercial partners leveraging plural funding routes and most spectacularly to define the terms of engagement. This project not only prefigured the convergence of ubiquitous mobile computing and social media but also resulted in a series of community based activities between 2004 and 2007 – called Social Tapestries – which took R&D aspects from corporate and academic labs fully into the public domain and in turn revealed the significance of public participation in terms of any effective R&D with respect to social media – a kind of liberation strategy which displays eloquently the value sense underlying the Proboscis operation. Here is an extract about the project:

‘Urban Tapestries investigated how, by combining mobile and internet technologies with geographic information systems, people could ‘author’ the environment around them; a kind of Mass Observation for the 21st Century. Like the founders of Mass Observation in the 1930s, we were interested creating opportunities for an “anthropology of ourselves” – adopting and adapting new and emerging technologies for creating and sharing everyday knowledge and experience; building up organic, collective memories that trace and embellish different kinds of relationships across places, time and communities.The Urban Tapestries software platform enabled people to build relationships between places and to associate stories, information, pictures, sounds and videos with them. It provided the basis for a series of engagements with actual communities (in social housing, schools and with users of public spaces) to play with the emerging possibilities of public authoring in real world settings’.

On the Daniel Langlois Foundation website (who provided funding towards the project) the language outlining what happened is different again:

‘What would freedom of expression be without the means to express it ? As fundamental as this concept is, it appears empty and abstract if you don’t complement it with the freedom to choose the means of expression. Today’s wireless communication networks offer novel ways to express ourselves. For the time being, these networks escape government or corporate control, which is why they are being used by many artists and activists to give this concept more concrete meaning’.

No doubt there were different spins to the narrative again on the websites of the different project partners – as clear an illustration as one might wish for of the pluralistic capacity of Proboscis during this 2002-2007 period acting as a broker, connector, and transdisciplinary catalyst. It is interesting that on the current Proboscis website, the ‘history’ section ends at September 2007 and before this that year Alice and Giles had visited Australia, Canada and Japan as well as taking part in numerous UK based events, conferences and discussions – being greatly in demand to un-layer and share tales of the Urban Tapestries and Social Tapestries adventures and outcomes. This work was intensive and significant with respect also to the broader history of collaborative media practices in the early years of this century.

The history of the period between September 2007 and now is also now still waiting to be written – and the turn which is now happening in relation to the direction of their work more explicitly revealed

Between Tactical Extremes

Taking further forward some of the ideological strands initially outlined in the goals for Topologies as well as running through the Urban Tapestries above, Giles writes currently on the Proboscis website about their forward programme for 2011 which will focus around the over-arching theme of Public Goods,

‘In the teeth of a radical onslaught against the tangible public assets we are familiar with (libraries, forests, education etc), Public Goods seeks to celebrate and champion a re-valuation of those public assets which don’t readily fit within the budget lines of an accountant’s spreadsheet’.

Showing this long-term commitment to core ideals, when I first met him in 1998, when commencing their Topologies project, Giles had written:

‘Public libraries are seen by Proboscis to be one of the UK’s most important cultural jewels, long-underfunded and lacking in support from central government. As sites for learning and culture they are unparalleled, offering a unique user-centred experience that is different from the viewer experience of a museum or a gallery’.

It is also ironic now writing this just after one of the biggest public demonstrations that London has known in the context of planned government cuts to the public sector and recalling that whilst the aim Proboscis had thirteen years ago was to add to the experience of visiting libraries by adding artists books into their holdings, the demise of the library system itself is now the battle along with devaluation and depreciation of many aspects of the public domain. Here one has a sense again of the uncannily fore-shadowing nature of many of Proboscis’s themes. Their antennae as sensitive collaborative creatures twitching often too soon?

Sustaining Partnerships

In exploring the way in which Proboscis set out to work in collaborative ways over many years one notes a serious attuning to context, making events and initiatives which often involve deep localised engagement with those with whom they have chosen to partner whether in public or private sector contexts. Often these partnerships are sustained over many years as for example with DodoLab in Canada with whom they have a long-term relationship that manifests in different ways in different places addressing social, urban and environmental challenges through artworks, performances, interventions, events, educational projects and publishing using social media, the Proboscis bookleteer and StoryCube initiatives and others ways of involving and communicating with people.

Other relationships have been related to specific projects; almost all take place over at least two or three years following a series of research questions or over-arching line of enquiry which requires focussed time and many different manifestations. The techniques which Proboscis bring to the table in terms of collaborations have been well-honed in various scenarios – as are well outlined and documented on their capacious website. Connecting these techniques for group interaction and group authorship with technological and industrial change and a corresponding shift in the cultural and social imaginary has been a prevalent element and thread which has emerged throughout a series of interrelated activities.

Re-drawing the Map

I developed a deeper understanding at first hand of the Proboscis effect when 2009 Alice Angus, Giles Lane and Orlagh Woods from the company were among a group of UK based arts technology and design researchers and practitioners who came to an event held in Sao Paulo called Paralelo with which I was closely involved. The event brought together individuals and groups working in three countries – the Netherlands as well as UK and Brazil – on topics and themes relating to Art, Technology and the Environment. Proboscis brought a beautifully honed process of group Social Mapping to the opening session of the event. This created a way of introducing individuals and everyone to everyone else with the plus factor that it gave form to the latent network connections that lay underneath, beside and across the topology composed on paper laid out on the ground. It was in many ways a characteristic Proboscis intervention inflecting the overall event with a collaborative and open-ended fluidity of approach with participants then returning to the map at the close of the event and in a ritual of consolidated iterative expression redrawing earlier lines, shifting to new points of intensity. This effect relies on an appreciation of ritual, of the act of drawing with the hand on paper, of making marks and leaving something that over time becomes a document of something that has now passed…

‘The development of new forms of expression is not something that is bound to happen, but is a matter of the choice and preference of artists. What is possible is the programmed creation of works. The artist is then creating a process, not individual works. In the pure arts this may seem anathema, but art thrives on contradictions, and it can be yet another way of asking what is art?…’

From first page of EVENT ONE, first edition of PAGE journal of Computer Art Society, 1969.

In their contribution to the book Paralelo: Unfolding Narratives in Art, Technology and Environment which emerged after the workshop in 2009, the Proboscis team also brought a singular simplicity (that held much deeper meaning than what was visible on the surface) to the project. Their text, Travelling through Layers, available also as a Diffusion eBook – holds in a small space a series of interleaving observations, images, quotes and commentary – all of which combine to build a narrative that stands alone or as part of the larger whole in this case the wider texts that make up the publication, a small microcosm of the broader Proboscis effect.

In Conclusion – The Latency of Glass?

As we enter into 2011 and shifts in political and arts funding scenarios, it seems to me that Proboscis are once again on the turn. Adapting to constraints that have emerged from socio-environmental contexts, they are taking a slower course. expressed in the lavishly vulnerable depiction of the disappearing markets in Lancaster which Alice has recently produced and the oft expressed commitment to providing tools and resources at low cost for others to access whilst wishing to do this by way of exchange and experiment – allowing social concerns to dominate technologies and allowing the reinstatement of hand and handi-craft into the Proboscis process.

It seems to me that with the usual fore-shadowing the organisation is now pointing towards a need for deep contemplation and reflection on what is currently in danger of being lost and following the ecological theme, seeking to ensure that we devise ways to recycle material back into the system. In some extent they are going out further to those margins and extremes, wanting to fuse together some new points of tension or heightened concerns. No doubt this will slowly and surely emerge.

And most importantly how does one articulate and measure value within these processes? What kinds of measurement can apply when one is talking about ‘effect’? What distinguishes their work from others who have moved into these spaces between the arts and other sectors? What has made them so effective in these spaces? And having moved in, developed systems of exchange and parallel processes with many other agencies, what has Proboscis gained and lost – what (apart from documentation on their website) might remain? Why do they move on? What do we learn from the textures and edges that their processes effect?

Their capacity to retain an integrity and critical edge whilst being involved in processes of exchange with many different types of partner organisation has been admirable; if as outlined in the 2010 Prix Ars Electronica Hybrid Arts text we might see hybrid arts practices as being fundamentally about an ontological instability or insecurity then in many ways the work of Proboscis throughout sixteen-seventeen years may be situated in this terrain.

Throughout the late 1990s and 2000s so far the best projects (and those which become most memorable) at least in relation to the broad field of collaborative and interdisciplinary arts practice seem to me to be those which tend to fuse together layers of different processes, systems and materials to form a new, highly charged synthesis that carries within it the tensions implicit in making something disparate whole. If broken or contracted, new edges will then emerge that redefine the boundaries of the whole.

Over time what is engendered and revealed are certain qualities manifest at both surface and depth – I describe these forms as having something like the latency of glass.

The Proboscis narrative has many of the properties of glass (fused to a point of stillness, yet with inner motion and capable of breaking to form new edges). If I have managed to identify at least one angle on their work using the perspective of the dark lens it is related to something Giles said in conversation in February 2011 about his interest in “exploring extremes and the points of tension between”. The photographic negative awaiting advent of light in the darkroom is another way of seeing this. Perhaps the phantasm of ‘true collaboration’ lurks in the latency of glass.

Bronac Ferran, April 2011

Telling Worlds by Frederik Lesage

April 20, 2011 by admin · Comments Off on Telling Worlds by Frederik Lesage

Telling Worlds

A Critical Text by Frederik Lesage