TKRN: reaching another milestone

June 30, 2018 by Giles Lane · Comments Off on TKRN: reaching another milestone

Recently a very exciting development has taken place which confirms our confidence in the usefulness of the TKRN project, and its potential to persist beyond the lifetime of the project itself. This milestone is the scanning and uploading of over 40 new TKRN notebooks created by people on the Rai Coast to the Reite village online library by Urufaf Anip, one of the Reite villagers, using the TKRN publishing kit we left in Madang for this purpose.

At the end of our last visit to Papua New Guinea, I spent two days in intensive media training with Urufaf and his sister, Pasen Anip. Neither has used a computer before, although both very familiar with smartphones. We started from basic introduction to the computer and how to switch it on, to exploring the file system and then to setting up email accounts. From there we progressed to using the web, and creating accounts for them both in WordPress so they could post material on the Reite online library site, and how to scan in completed notebooks as multi-page PDFs, name the files and generate images of the front covers.

As we were about to leave PNG, James and I put together a document (in both English & Tok Pisin versions) to remind them of the various steps involved in each process that they could refer to next time – knowing that a one-off intensive training session would never be enough to embed the learning required. Fortunately, the project has been supported by Banak Gamui of the Karawari Cave Arts Project based in Madang, who are hosting the TKRN publishing kit, providing internet access and help with using the technology. Banak’s assistance has been invaluable both in hosting the kit and supporting Reite people such as Urufaf to come into town and help with familiarising them with how to use the computer and the internet to scan in and store online versions of the books they make.

It has been a long journey since our first notebook experiment in 2012, but we have now arrived at a point where Reite people are able not only to complete the physical paper notebooks, but have the capability and competency to digitise them and upload them to the internet for long term preservation. Our trip to the village last month also bore witness to a resurgence in people’s desire to teach and learn their traditional local language, Negkini, as a crucial factor in cultural and social cohesion. There was lots of interest in using the TKRN books to begin writing in Negkini (something only first attempted a few years ago) – both by individuals in the community as well as from teachers at the local school. This suggests so much possibility for cultural renewal and enrichment, especially when combined with the digital skills and capabilities being demonstrated by Urufaf – indigenous public authoring is becoming a practical reality, much more than a vision for what might be possible, or a dream.

TKRN: Groundwork for Legacy

May 21, 2018 by Giles Lane · Comments Off on TKRN: Groundwork for Legacy

It is now more than five years since my first visit to Papua New Guinea and Reite village, on Madang Province’s Rai Coast. I’ve just completed my fourth field trip there with anthropologist, James Leach, where we have been conducting the first stage of a 2 year legacy and handover phase for TK Reite Notebooks, supported again by The Christensen Fund. Our aim is to establish a firm base for Reite people to have control over the tools and techniques we have co-developed with them, and for them to have both the confidence, capability and capacity to share not only their own Traditional Knowledge with others, but to train other communities, who wish to adopt it, in the TKRN Toolkit‘s use too.

Over the years we have been exploring potential partnerships with local organisations both in PNG and in Vanuatu, hoping to build a network of support for TKRN and those using it. Last year James met with Banak Gamui of the Karawari Cave Arts Fund – an NGO based in Madang – who is active in supporting traditional cultural preservation and regeneration initiatives in Madang Province, including the Madang-Maror Network. Banak agreed to help support Reite people continue to use the Toolkit beyond the project’s end, by hosting the basic publishing kit (laptop, printer & scanner) at KCAF’s office and strengthening Reite’s connections with other communities in the area also active in practising, documenting and preserving Kastom culture. In addition, Yat Paol, of Gildipasi/Madang-Maror, was also able to broker a connection with Bismarck Ramu Group, another local NGO which supports communities retain their land and water rights against extractive development. BRG agreed to host a 3 day workshop and 18 participants from Reite and its neighbouring villages, Marpungae, Asang, Soriang and Sarangama, travelled up to Madang to take part, along with Banak Gamui, Yat Paol and Catherine Sparks – formerly Melanesia Program Officer of The Christensen Fund.

Over these days, we increased the core group we had been working with from the village and undertook refresher training in making and using the notebooks co-developed previously. Much time was also spent in discussions about what exactly TK (Traditional Knowledge) means to people for whom it is still an everyday practice – rather than a ‘heritage’ practice as many Western traditions are often relegated to. One of our key Reite collaborators, Urufaf Anip of Marpungae, came up with a popular transliteration – Timbuna Kastom – which seems to capture much of what is both special and at risk about their way of life. Timbuna could be understood as the ancestor spirits which animate the bush, as well as descendants and those to come. Kastom is the traditional way of life that communities in PNG followed for countless generations before the arrival of missionaries and colonialism. As both Christianity, the money economy and industrial development (mining, logging, monocultural farming, factory fishing and other extractive processes) have supplanted traditional beliefs and ways of living, so more and more Papuans have found their connection to land, bush and water have been severed, and their lives made more precarious.

This connection is at the heart of what makes this project such a timely opportunity to revitalize social cohesion and knowledge transmission around the importance of those communities which have retained a strong traditional culture. The workshops also underlined the crucial importance of Tok Ples – local language – which is the blood of Timbuna Kastom/Traditional Knowledge’s beating heart. PNG has over 800 individual languages (not dialects) – with some ranging from just a few tens to thousands of speakers. Until very recently, communities across PNG were almost exclusively oral in culture, writing and literacy being a product of interaction with traders, missionaries and then colonial administration. But there is an intensely rich visual culture – each community creating unique designs reflected in their crafting of objects and decorations as well as styles of house building. Designs are often deeply symbolic, communicating specific stories and meanings, or relating to particular locations. Language and visual design are thus deeply intertwined with the particular geographies and environments which PNG’s many and diverse communities inhabit and steward. Maintaining and strengthening this diversity is as crucial as maintaining the diversity of plants and seed banks for genetic variety. PNG’s school system still teaches predominantly in English, and over the years Pidgin, Tok Pisin, has become the main national language, to the point now where children in many communities are not being brought up to speak their local Tok Ples first, but Pisin instead. As the unique relationships to place are loosened in this way, the connection to land slackens and people are persuaded to register and sell their land to outsiders. For a country where around 80% of people are still reliant on subsistence food production (through their gardens) this is clearly catastrophic.

On the wall of the BRG Community Room where we held the workshop, there is an inspiring quotation from PNG’s 1975 Constitutional Planning Committee:

This is placed next to a copy of the PNG National Goals and Directive Principles:

The workshop provided us with a space and place to collectively retread the ideas and experiments of the past 5 years, and to reiterate the aspirations and ambitions for what the tools and the continued practice of kastom means to traditional communities. Being held in a less isolated and rural setting it also gave us the opportunity to demonstrate the digital aspects that are harder to achieve in the bush: scanning in notebooks and uploading to the online library which we created for Reite. Although almost all the villagers have never used a computer before, are completely unused to keyboards and have only a slim grasp of the workings of file systems and structures, windows and desktop metaphors – they acknowledge the potential benefits that this form of recording and sharing can offer them and are quick to learn it use. Two people (Urufaf and his sister Pasen) were chosen to be the leaders of this activity and to receive additional training later in our visit.

The workshop had been programmed to precede and important ceremony in the village, and on its conclusion the villagers, James, myself, Banak, Catherine and Yat’s wife and son made the day-long journey in two small dinghies across Astrolabe Bay and down the Rai Coast, then up 400m above sea level and 10km inland to Reite village, where we would be staying. Over the next days a series of ceremonies and events took place that demonstrated Reite’s strong hold on kastom, the richness of their culture, and just how keenly people wish to continue this way of life into the future and for the benefits of future generations. We took part in a night-time Tamburan event (a performance of secret, sacred instruments) that began in the bush before moving into a Haus Tamburan itself. This was followed the following day by a large kastom food distribution between one village and families of another, followed the next day by a reconciliation payment ceremony and the all-night Singsing to conclude the festivities. In amongst these ceremonies, James, Banak, Catherine and I were invited to address the local school (which James and I worked with back in 2015) about our respective projects and the importance of traditional culture, tok ples and caring for the environment.

The ceremonies over, we rested for a day then returned to Madang for a final couple of days intensive media training with Urufaf and Pasen. This involved introducing them both to the computer from first principles, getting them used to using it for scanning documents, file management, email and using the internet. With the assistance of Banak & KCAF in Madang, and from me remotely from the UK, we will be supporting them gradually take over the maintenance of the Reite Online Library – scanning and uploading completed TKRN notebooks and expanding the resource. As their confidence and fluency with digital technologies grow, there is the potential to increase their skills to include designing their own notebooks and using bookleteer to generate their own publications.

The success of the workshop at BRG and the excitement generated in the village during the ceremonies, has had a significant effect in making the longer term aspirations of the project begin to see light. Reite people are growing in confidence and desire to share this method of practicing and documenting culture and kastom to other interested communities in the region and, in so doing, to establish a name and reputation for themselves. Plans are already underway for a Reite to host a group of representatives from other Madang Province communities next year to demonstrate this and share the TKRN Toolkit and training.

More TKRN work in Papua New Guinea

May 27, 2016 by Giles Lane · 3 Comments

I’ve recently returned from Papua New Guinea where, with James Leach, I have been doing field work for our TK Reite Notebooks (TKRN) project. This follows on from our work last year in Reite village on Madang’s Rai Coast, and also from our trip to Vanuatu in February, where we worked with a group of women fieldworkers and the Vanuatu Cultural Centre.

Having established the model of working with the notebooks with Reite villagers last year, the focus of our trip in this second year of the project was not to produce more books, but to explore how and if the model would work with other communities and, to find other local partners for whom the tools and techniques we have developed could be useful additions to their own methods and practices of documenting traditional knowledge.

Through our close discussions with Catherine Sparks and Yat Paol of The Christensen Fund (our project’s main sponsor), we identified some possibilities – the Research + Conservation Foundation (RCF) of Papua New Guinea (in Goroka, Eastern Highland Province); and Tokain village, Bogia District (Madang Province). Having arrived in Madang and met up with two of our key collaborators from Reite – Porer Nombo and Pinbin Sisau – we made plans to travel up the coast to the village of Tokain and stay a few days to introduce our model to local people. James and I then travelled to Goroka to spend a day at RCF meeting with their director, Sangion Tiu, education programme manager, Emmie Betabete, and resource officer, Milan Korarome. We learnt about RCF’s work in communities and in teacher training, and presented our TKRN approach. This resonated strongly with RCF whose staff spoke of the problem of documenting traditional knowledge in both school and village settings. It was a lovely moment when their enthusiasm for the books spilled over and we decided on the spot to co-design a new template with them. We then spent a while devising questions about climate change for elementary schoolchildren, which RCF will pilot this summer.

We returned to Madang after this highly successful meeting and the next day set out for Tokain with Porer, Pinbin and another young man from Reite, Urufaf, who has become a key proponent of using the TKRN books in his own community. Piling aboard a PMV (an open back truck with benches and a tarpaulin for sun/rain cover) we bumped along the highway following the coast north for about 4 hours before arriving. Many people from the village turned out to meet us and hear Porer, Pinbin and James introduce what the Reite villagers had done with the TKRN books and why it was important to them to preserve and transmit their culture and knowledge to future generations this way. The following morning we walked around different parts of the village meeting people going to market and in the community office, where they have a laptop and printer/scanner of their own, giving us an opportunity to demonstrate the whole cycle of printing off a PDF booklet, filling it in, scanning and storing it as a PDF on the computer and printing out another copy of the scanned book.

Then we addressed all the students from the elementary and primary schools, their teachers and some of the village elders – again, the focus being on the Reite villagers explaining their use of the books and how the school in Reite had adopted the books as part of their own curriculum activities on environmental science and cultural heritage. This indigenous or local exchange of documentation practices (with James and myself taking a secondary role as facilitators rather than teachers) is very much the beginning of where we see the TKRN model developing in the future. The afternoon was spent workshopping ideas for the booklets and getting people used to the cutting and folding process for making up the books, as well as taking their photos to stick onto their books – always a popular aspect of the process. This continued well into the night with the convivial atmosphere of a house party surrounding the guesthouse where we stayed.

We left Tokain having agreed to meet up in a week or so’s time with a representative from the village who would bring us the first batch of completed books to scan and for me to build a simple website for – as I did last year for Reite (Reite Online Library).

From Madang we set off across Astrolabe Bay and down the Rai Coast to return to Reite for a few days and discuss with the community what had happened since our last field trip and what we proposed to do next. A meeting was organised and many people also came from neighbouring villages and hamlets: Sarangama, Asang, Marpungae and Serieng. Porer, Pinbin and Urufaf all spoke about the project, what was achieved last year, what we had just done at Tokain and how important it is for knowledge to continue to thrive and be passed on to future generations despite all the changes happening to the world around them. James also spoke of our visit to Vanuatu, how we had shared some of the Reite books with the indigenous fieldworkers there and we showed them some of the books made by the ni-Vanuatu people we met.

The response was dramatically positive, with people calling for a revival of teaching and learning in their traditional local language, Nekgini, alongside using Tok Pisin to document stories and practices. A core group of people interested in taking the lead to build up a library of traditional knowledge also emerged, a group who were also prepared to go ‘on patrol’ to other local villages to share with them the TKRN methods. We left over 250 blank books in the village, as well as a simple to operate Polaroid Snap camera (and several hundred sheets of Zink photo paper) to take and print out photos of people to stick on the front covers. By shifting the focus from the familiar and everyday towards the more esoteric, and perhaps endangered, types of knowledge of their environment that Reite people have, we are hoping they will be able to develop a truly unique and exemplary library that could inspire others across PNG, Melanesia and perhaps even farther afield to document their traditional knowledge before it is lost. We also took the opportunity to improve the design of the books, redesigning the front covers to allow for more contextual information about the author and the books contents, and rewriting the engaged consent statement on the front for better clarity.

Returning again to Madang we met with Ernest Kaket from Tokain and scanned in the books he’d brought with him from the village. These now form the foundation of their own online library which we hope to expand in due course.

Our next steps are to make a return visit to Vanuatu with a couple of Reite villagers to introduce their use of the TKRN model themselves; and to continue to develop the basis of a partnership with RCF as a means of extending the reach across PNG of the tools and methods we’ve co-created with Reite people.

Reite Village Online Library

September 21, 2015 by Giles Lane · 4 Comments

This website has been created as an online library of TKRN notebooks made by the villagers of Reite and its neighbours in Papua New Guinea’s Madang Province. These books were created during a field trip in March 2015 and we hope to add many more in the future. We aim to transfer management of the site to the villagers themselves in due course, so that they can continue growing the library for future generations. As 4G mobile internet service penetrates into the jungle where they live and more local people own smartphones and connected devices, this is an increasingly likely possibility.

Mixing the physical and digital in this way means that traditional knowledge and customs may be preserved and transmitted forwards by embracing some of the changes that industrialisation and urbanisation bring to traditional rural communities. By working alongside the existing relationships of knowledge exchange it offers new opportunities for inter-generational collaboration on self-documentation of stories, experiences, history and practical knowledge of working with and sustaining the local ecology and environment.

The site itself is extremely simple and uses only free services: a free WordPress.com blog as the primary interface for organising and sharing the books; and a free Dropbox account as the primary repository of the PDF files of the scanned books. It is a key component in our TKRN Toolkit, and closes the loop in our use of hybrid digital and physical tools and techniques.

The villagers themselves developed their own categories and taxonomies for cataloguing the books, which have all been tagged accordingly. The books are thus searcheable by title, author and subject(s). Many of the books include an author photo on the cover page; a thumbnail image of the scanned book was included in each post, and a blog theme chosen that presents the main page as a mosaic of images from the posts. For communities with highly varied literacies, it also enables visual recognition both of the author’s faces, and in many cases their handwriting or drawing style.

TKRN Blank Notebooks

September 17, 2015 by Giles Lane · 4 Comments

These notebooks have been co-designed with villagers of Reite in Madang Province, Papua New Guinea by Giles Lane and James Leach as part of the TK Reite Notebooks project and Toolkit. They can be downloaded, printed out and made up into physical notebooks for recording traditional knowledge. Then they can be scanned and shared online or as physical objects.

The books have been created using bookleteer – Proboscis’ free self-publishing platform. Each link is to an A4 PDF file. The “view options” links open each notebook’s page in bookleteer with US Letter PDF and a web readable version.

16 page Standard Notebook with Questions – Tok Pisin • view options

16 page Standard Notebook with Questions – English • view options

16 page Teaching & Learning Notebook with Questions – Tok Pisin • view options

20 page Multi-stage Processes Notebook with Questions – Tok Pisin • view options

16 page Story Notebook with Questions – Tok Pisin • view options

12 page Initiation Notebook with Questions – Tok Pisin • view options

16 page General Purpose Notebook (No Questions) – Tok Pisin • view options

16 page Structured Notebook with Question – Bilingual Tok Pisin/English • view options

View the TKRN Notebooks collection on bookleteer.

We also have created this guide to folding and making up the notebooks (in English/Tok Pisin) :

TKRN Toolkit

September 17, 2015 by Giles Lane · Leave a Comment

TK Reite Notebooks is a toolkit for documenting and transmitting traditional knowledge to future generations. The essence is indigenous self-determination over knowledge.

The toolkit combines digital technologies and paper.

It is low cost, simple to use and can be easily adapted for different communities and languages.

The toolkit was co-designed with Reite villagers from madang Province in Papua New Guinea, with support from The Christensen Fund.

Versions : English | Tok Pisin | Bislama

Access all PDF Notebook templates here

Download a short version of the toolkit here (PDF)

Download Full Toolkit Instructions here (PDF)

The Toolkit below is divided into 3 Sections: Making; Sharing & Technical.

MAKING |

|

What you need:

|

|

| What to do: | Why? |

| 1. Identify the people who you will work with, and discuss the possibility of documenting Traditional Knowledge through this toolkit. Discuss what they might like to document, and what the value of recording it will be for them. | The toolkit support people who want to document, preserve, and/or transmit aspects of their traditions or knowledge. It is for them to decide how they will use it. If you are collaborating with a community of group, it is vital to agree on fundamental aspects such as who will be involved, who will benefit, and who will have control over, and ownership of, the results |

| 2. Make it clear that participation is voluntary, and that there are ways of restricting content built into the process. (You may use the engaged consent model developed with Reite Villagers) | It is crucial that everyone involved in the process understands certain things about it, and has a chance to consider others:

a. it is voluntary. |

| 3. Choose from notebook templates available here, or design you own. | Notebook templates have been designed in Tok Pisin, in Bislama, and in English. They are of various lengths, and with different prompts and guidance. You can choose one or more of these as suitable to your requirements. Alternatively, using bookleteer, anyone can design and create their own blank notebooks in different languages, for different contexts, or with different communities. |

| 4. Print the number of notebooks that you think you will use. Depending on conditions and resources, you might choose to use a waterproof paper instead of standard office paper. Keep the pages together in the same order they come out of the printer. Make sure people have enough scissors to make up the notebooks. |

The toolkit is based around the use of these notebooks. People use them to document anything they choose. Waterproof paper (e.g. Aquascribe) is more durable in humid environments.The PDF files print out the pages of the notebooks in the correct order. Shuffling the pages around will mean they might not be folded into notebooks successfully.Scissors are necessary to make up the notebooks from the printed sheets of paper. (You may have to supply these.) |

| 5. Organise public meetings or private discussions with the participants to demonstrate how to make and fold the notebooks

Discuss how people could use them, and the different kinds of content they might like to enter into them. This is to enable people to understand the notebooks and how they can use the notebooks and how they could write, draw, or add other kinds of content to them. (You may like to show some examples of completed notebooks that have been made by other communities as examples.) |

It is very important that participants fold, cut and make their own notebooks. Learning to fold notebooks engages people and offers ownership of a key part of the process. There is also a sense of achievement in making one’s own notebooks. People who have learned to fold the notebooks can teach others, or assist in folding workshops. In a large-scale documentation process, this also means one or two people are freed from making up multiple notebooks.

People should choose their own content. Meetings are an opportunity for people to co-operatively decide what is appropriate to record and how the process should be organised. They help people take control over their own documentation project. It is also doing things together: a common activity which motivates people to engage with each other and think about different types of Traditional Knowledge. Meetings make it possible to discuss concerns, and head off disputes over what should or should not be recorded before the notebooks are filled in. Things to keep in mind are:

|

| 6. Personalise the notebooks. Take a photograph of each person or group of people who will fill out a notebook. Print the photograph out and stick it on the front cover. Ask them to write their name(s) after the engaged consent statement. |

The photograph serves to identify the authors, to personalise the notebooks, and gives people an extra impetus to complete them. It also makes whatever is recorded there associated with this person and therefore keeps knowledge attached to people. |

| 7. Ask if they wish to delete any of the lines on the engaged consent statement. Double check that they understand and agree to the statements. | The engaged consent statement is a simple way to get people to think about what they record. Its asks them to think how willing they are for it to be seen by other people. This is important for several reasons, including taking ownership of the documentation process, controlling the circulation of the notebooks, and considering the nature of, and restrictions on, knowledge before making it public. In order to feel confident that they will retain control over the content it is vital to remind people that they are making these notebooks for themselves and for those they wish to pass things on to. Make it clear that they can restrict the circulation of the notebooks completely if they wish. This reminds them they are not being asked to record things for outsiders but that, if they are willing, other people can be given access to their notebooks they make. |

| 8. Make sure participants have writing and drawing materials. Distribute pens and pencils if necessary. | |

| 9. Remind people to be as full and complete in their documentation as possible. Encourage people to use all the space available, and to use drawing, images, photographs etc. as well as words. Its is possible to make longer documents by using more than one notebook with numbers indicating the order in which they should be read. |

People often assume a lot of background knowledge, or take for granted that the reader already knows the content. Ask them to consider what they would like their grandchildren’s grandchildren to know if they had never been in the village/area etc.. Suggest people give enough information so that someone with no knowledge of a plant or process or story could identify it, or follow it properly. |

| 10. Agree on a day and time when the completed notebooks will be returned for scanning (if required). | This encourages completion. Some participants will be enthusiastic and wish to complete multiple notebooks. Others may be shy of their ability and need a deadline to complete the work. |

| 11. Be available and encourage questions and concerns to be shared while people are in filling out the notebooks. Respond positively to new ideas for content, or to suggestions about what people would like to document. |

This means people who become confused, or lose confidence in what they are doing, will not just drop out of the process. People are often shy or feel ashamed to document obvious material. Participation can be more important that what is actually recorded. |

| 12. Digitise the completed notebooks. First confirm consent to scan and/or share online by giving people another chance to modify the consent statements on the front of the notebooks. Unfold the booklets, scan the individual pages as either jpeg images or PDF pages. Collate all the scanned pages for each individual notebooks into a single PDF file, and give it an appropriate file name. |

Digitising the notebooks will allow them to be archived and shared, or printed out again if the original is lost or damaged. Scanned notebooks are permanent records and can be the basis for a library of local knowledge and practices. |

| 13. Put each notebook back together and return it to its author. | Immediately returning the notebooks is an important way to keep the documentation with participants, and can be reassuring for them. |

SHARING |

|

| 14. Share files via removable media. Copy files to USB flash drives, or microSD cards of people involved in the project. Alternatively, each scanned notebook should be small enough to email.

15. For those with sustained access to the internet, we recommend building a simple website which can act as archive of uploaded PDFs of the notebooks. Visit the online library website created for Reite village for inspiration and ideas. Websites can either be open or private. 16. Print out copies of the notebooks, fold and make them up for the establishment of a library of physical copies of the notebooks. This might be hosted by a local school, community centre or institution. |

|

TECHNICAL |

|

The project only uses freely available digital and paper technologies. The most basic tools required are pens, paper and scissors, with various digital technologies adding increased capabilities at different levels :

Creating New Notebooks Making Up Notebooks Paper Stock Adding Images Scanning & Printing Sharing & Distribution Another simple sharing method is to copy PDF files of scanned notebooks onto cheap USB flash drives or MicroSD cards which can typically store thousands of files. Power & Light We tested a range of solar lights in the village and recommend these : Sun King Pro All Night (via SolarAid in the UK) and the Nokero N182 Solar Light Bulb. |

|

The toolkit is licensed under Creative Commons.

TK Reite Notebooks

September 17, 2015 by Giles Lane · 10 Comments

Documenting and practicing Traditional Knowledge

for future generations

TK Reite Notebooks is a toolkit for documenting and practicing traditional knowledge for future generations. At its heart is a respect for indigenous self-determination. The toolkit combines digital technologies and paper. It is low cost, simple to use and can be easily adapted for different communities and languages.

TKRN Toolkit | Project History | Activities | Outputs | Outcomes

Project History

TK Reite Notebooks (TKRN) is a process and tools with which people can self-document Traditional Knowledge (TK). It results from a meeting of ideas and practices of social anthropologist James Leach, artist Giles Lane and the people of Reite Village on the Rai Coast (Madang Province) of Papua New Guinea. It extends, in a new way, a long tradition of collaborative documentation of TK pioneered in Papua New Guinea by Saem Majnep and Ralph Bulmer.

During James’s long association with people in Reite village (since 1993), their desire to document, preserve, and find ways to ensure the inter-generational transmission of knowledge has been at the forefront of the relationship. This desire, realised to date through anthropological and ethno-botanical publications, finds a different engagement through TK Reite Notebooks. The project grew from James’ anthropological work with Reite people, and in particular, the collaborative documentation of plants undertaken with Porer Nombo, published as Reite Plants. TK Reite Notebooks now involves many Reite people in the co-design of a ‘toolkit’ offering people an accessible, cheap, locally appropriate and adaptable process for TK documentation.

The TKRN concept has also grown extensively from Giles’ long term artistic practice of developing and facilitating “public authoring” – drawing upon his Diffusion eBook format and the self-publishing platform, bookleteer, which he has led and maintained. Public Authoring emphasises ways and means for people to document, for themselves, what they find valuable, and to share it with others, making use of the wide panoply of media – digital and physical – that are available to them.

The project is supported by US foundation The Christensen Fund whose work in Melanesia aims to support the holders of traditional bio-cultural knowledge as they work to maintain their rich ecologies, often in the face of huge pressure from resource extraction and social change. Further support comes from the Australian Research Council through a ‘Future Fellowship’ award to James Leach to investigate appropriate modes to present socially embedded knowledge forms, and from the Centre for Research and Documentation in Oceania at Aix-Marseille University.

The TKRN Toolkit is based on the use of bookleteer.com, an innovative self-publishing system that moves fluidly between paper and digital. Using this process, we have co-designed a series of notebooks with prompts that guide people to determine for themselves how to document and record Traditional Knowledge and practices. These notebooks can be easily digitised and shared online for archiving and for ‘practicing’ with and for future generations.

Explore Reite village’s online library of TK Reite Notebooks. View a sample notebook below:

Activities

A pilot study in 2012 established initial notebook templates that were co-designed with Porer Nombo and other Reite people. This provided the foundation for a more extensive and in-depth project, which was awarded funding in 2014, with fieldwork beginning in February 2015.

The first year of TK Reite Notebooks has involved a more extensive engagement in Reite to co-design more booklet templates, experiment with their use, and investigate how they well they fit with peoples’ interests and priorities. Engagement with the local school demonstrated the value of the toolkit in educational contexts, and an elaboration of the basics for a handbook addressing the process, ethics, technology, and potential of the toolkit was achieved.

Liaison with colleagues with extensive experience in TK documentation, including Dr Robin Hide of Australian National University (ANU), situated TK Reite Notebooks within a wider view of past and present initiatives.

In 2016 we tested the toolkit with another community in PNG : Tokain Village, Bogia District (Madang Province) as well as developing a collaborative relationship with the Research + Conservation Foundation (RCF) of PNG (Goroka, Easter Highlands Province) to use the TKRN toolkit with the communities they work with across PNG. We have also extended the project to Vanuatu: working with the women fieldworkers group of the Vanuatu Cultural Centre (VKS), the Vanuatu Land Defence Desk, the Heritage Section of the VKS, the Tanna Ecologies Youth & Gardens Project and with youth groups and their communities in partnership with Wan Smolbag Theatre in Port Vila, Efate. To facilitate an indigenous knowledge exchange between PNG and Vanuatu, we participated with 3 Reite villagers in the Tupunis Slow Food Festival held on Tanna island, Vanuatu in August 2016.

In 2018 we began a legacy phase aiming to leave Reite villagers with the capability to continue to use the toolkit and grow their online library of books without external help, and to provide them with the means to train other interested communities in how to use the toolkit and create the books.

The Toolkit is free and adaptable under a Creative Commons license – having been co-designed by an indigenous community living a traditional subsistence based lifestyle we believe that it can be simply and easily adapted by and for other communities across the world who also live traditional lifestyles and are concerned to document, preserve and co-practice their knowledge for future generations.

Posts :

- 2009 UK: visit to the UK by two Reite villagers

- 2012 UK: Preparation for PNG trip

- 2012 PNG: Saem Majnep Symposium & Reite village pilot study

- 2015 PNG: Reite co-design collaboration

- 2016 Vanuatu: Vanuatu Cultural Centre

- 2016 PNG: Further iterative design (RCF, Tokain & Reite)

- 2016 Vanuatu: Wan Smolbag & Tupunis Festival Cultural Exchange

- 2018 PNG: Legacy Workshop & Training with BRG/KCAF

Outputs & Resources

Toolkit

We have created a simple toolkit that can be adopted and adapted by others. We have co-designed a series of notebooks that Reite and Sarangama villagers, and Reite Community School are using. This design is an ongoing and iterative process – we have created additional custom notebooks for RCF, VKS, Wan Smolbag Theatre and for the Tanna Ecologies Youth & Gardens project.

Reite Online Library

We have created a TKRN website (using free web services and software) for the village of Reite and its neighbours, where the booklets they produce can be saved, viewed, and accessed. This website is intended to provide a model for other users to develop their own sites to archive their own TKRN notebooks – a similar site has now been created for Tokain Village.

Outcomes

Engagement

Key outcomes have been the high level of engagement of people from the villages of Reite, Sarangama and their neighbours.

- About 150 people took part in a series of initial public meetings in 2015 explaining the project and what we hoped to achieve.

- Around 12 people assisted in co-designing new and alternative booklet templates, and in testing these templates through utilising them.

- Collaboration between the generations in making booklets was extensive in the village. Those with limited literacy tended to seek out younger people to write for them. Many, both literate and illiterate engaged in careful and beautiful illustration.

- 63 Notebooks were completed by 42 people during a two week period.

In 2016 we continued to engage with diverse groups in both PNG and Vanuatu:

- Introduced 16 ni-Vanuatu women fieldworkers of the VKS in using the notebooks, plus several other VKS staff in the heritage section and members of the Vanuatu Land Defence Desk;

- Trained around 50 people in Tokain village to use notebooks and toolkit

- Workshop with around 200 schoolchildren teachers and elders at Tokain School

- C0-designed or updated at least 17 new notebook templates in Tok Pisin & Bislama

- About 100 people from Reite and local villages attended a public meeting to discuss outcomes from the project and plans for the future

- Participated in the pan-Melanesia Tupunis Slow Food Festival on Tanna island with 3 Reite villagers

- Ran toolkit workshops with Tanna youth group

- Ran toolkit workshop with youth group & staff at Wan Smolbag Theatre, Vanuatu

Involvement of Local School

In addition, the headmaster and senior teachers of Reite’s Community School asked for a demonstration of the process at the school.

- Practical demonstrations of booklet making were undertaken with all 8 year groups. In response to requests from the school, James gave a series of talks to the whole upper school on the importance of ecology, traditional knowledge and how it relates to environmental science, a key component of the PNG national curriculum. The use of TK Reite Notebooks in this way demonstrated a model for how the toolkit could bridge traditional knowledge and formal education, and additionally, how the toolkit created a new opportunity for inter-generational co-performance of knowledge, again bridging the concerns of educators and the concerns of village people.

- An additional 290 booklets were printed and made with the assistance and resourcing of the school.

- 55 notebooks were completed in less than a week as a result of the students creating their own notebooks with elders and family.

- The school developed appropriate assessment criteria for each achievement level that related to the use of the notebooks. The notebooks were seen to be valuable because the activity had application in at least four educational priority areas: environmental science, social science, language and communication, and art.

- In 2016 we introduced the toolkit to staff and students at Tokain village school as part of our visit as well as co-designing a special climate change notebook with RCF for use with primary school students

The Papua New Guinea Department for Education supports a focus on TK under the National Curriculum areas of science, and culture and community. The National Curriculum Statement states that:

The knowledge and intellectual resources of Papua New Guinea, developed here over thousands of years, are in danger of being lost as young people lose contact with their traditions and heritage. Science education has a role in encouraging students to learn about this rich source of knowledge.

National Curriculum Statement for PNG, Dept of Education (p. 28 2003).

External Interest

Papua New Guinea villagers typically have extensive and elaborate mobility, or multiple connections to people outside their own place. Word spread very quickly about the toolkit process and a number of requests for the toolkit to be made available in other places emerged. An outcome of the use of the booklets in both the village and the school contexts was an increased awareness, external to Reite, of the possibility of, and desirability for, documenting and valuing traditional knowledge. In year 2 we were able to extend the project both to another community in Madang Province (Tokain) and to support a core group of Reite villagers who have been introducing other local Rai Coast villages to the toolkit. In addition, the project’s scope extended to neighbouring Melanesian country, Vanuatu, where we have collaborated with the Vanuatu Cultural Centre and its fieldworker and heritage programmes, as well as Wan Smolbag Theatre, the Vanuatu Land Defence Desk and Tafea Cultural Centre on Tanna. We are currently developing collaborations with the Research + Conservation Foundation of PNG in Eastern Highlands Provice, Maror indigenous organisation in Madang, and the Indigenous Research Centre in Bougainville to help them both adopt and adapt the toolkit for their own community documentation projects.

Relevance to Local Culture & Community

The booklets are not necessarily coherent or intelligible to audiences outside the local context. Noting this is important. It makes clear a distinction between TK Reite Notebooks and traditional ethnographic techniques which seek to explain traditional knowledge practices to outsiders. The beauty of much of the documentation already completed by Reite people suggests that they are already finding modes of expression for TK that are tailored to their intentions around it. (These include, for example, relationship building, the demonstration, or performance, of knowing and ownership rather than an encyclopaedic approach to making a catalogue.)

Technical Development

We hope in the future to effect a major technical upgrade of bookleteer.com to make it more accessible to people living in non-industrialised settings without immediate access to the internet, computers and printers. We have so far done some simple feasibility studies into porting a version of the platform to run on an Android-based smartphone, for use in off-grid contexts where internet access is patchy or unavailable. This will be designed to synchronise with the main bookleteer server as and when internet access becomes available (e.g. by taking the phone to a local town), and will also incorporate as simple method for scanning and sharing handwritten notebooks using the phone’s camera.

Legacy Phase

In 2018 we returned to Madang to lead a ‘handover’ workshop for Reite people and local partners including Yat Paol of Tokain community, and Banak Gamui of the Karawari Cave Arts Fund. The workshop was generously hosted by local NGO, Bismarck Ramu Group, which “informs, trains, advises and helps empower people so they can make informed decisions, confidently speak out, organise and take action to protect and maintain control over their land, resources and livelihoods.”

A further trip in 2020 is anticipated to result in an event in Reite itself to bring people from around the region to the village and to learn about their culture and practices in situ, and the role which the TKRN project and books have played.

Credits

Villagers of Reite & Sarangama, Madang Province, Papua New Guinea, Pinbin Sisau, Giles Lane, James Leach & Porer Nombo

Supported by The Christensen Fund

Pilot Phase : 2012

Main programme : Begun 2015 | Completed 2016

Legacy Phase : Begun 2018

To Papua New Guinea

October 23, 2012 by Giles Lane · 2 Comments

Tomorrow I start my journey to Papua New Guinea where I’m taking part in the Saem Majnep Memorial Symposium on Traditional Environmental Knowledge (TEK), hosted by the University of Goroka (Eastern Highlands Province) and supported by the Christensen Fund. The title and abstract of my talk at the symposium is:

Digital and Physical : simple solutions for documenting and sharing community knowledge

My work is about engaging with people to identify things which they value – for instance knowledge, experiences, skills – and how they can share them with others in ways that are safe, appropriate and inspiring. As an artist and designer I have helped devise simple tools and techniques that can be adopted and adapted by people on their own terms – such as uses of everyday paper, cameras and printers alongside digital technologies such as the internet, archives and databases. I will demonstrate some examples of how these simple physical and digital tools can be used to share community knowledge in freely and easily accessible ways, so that they can also be re-worked and circulated in both paper and digital formats. I hope to offer some examples of how TEK in PNG might be widely documented and circulated as part of commonly available resources.

I wrote a piece about my initial thoughts on what I’ll be presenting and doing whilst I’m there on the bookleteer blog last month. My invitation to this event has been through James Leach, Professor of Anthropology at the University of Aberdeen who will be there presenting his collaborative publication, Reite Plants, with Porer Nombo in whose village James has been doing fieldwork for 20 years. I first met Porer three years ago when he visited the UK to assist the British Museum’s Melanesia Project in identifying artefacts from the region where he lives in the Ethnographic Collection. At the time James had asked me to help him devise some new ways to document this kind of Traditional Knowledge Exchange that would capture something of the experience of all sharing knowledge that more institutional methods might miss. Consequently we used some Diffusion eNotebooks to capture and record our interactions as much as the stories and information that Porer and Pinbin shared about the artefacts. Alice and I also had the privilege of spending time with Porer and his fellow villager, Pinbin Sisau, inviting them to our home for an evening with James and his family and sharing with them some of the simple delights of central London life that people who don’t live here wouldn’t experience.

After the symposium James, Porer and myself will travel back to Porer’s village of Reite on the Rai Coast in Madang Province where we’ll stay for a week or so. There we’ll attempt to put some of our ideas into practice – I’ve designed some simple notebooks for us to use out in the bush, some printed on waterproof paper, others printed on standard papers. I’m very excited to have this unique opportunity to test out ideas I’ve had for using the Diffusion eBook format and bookleteer in the field for over 10 years now – harking back to conversations I had with anthropologist Genevieve Bell of Intel in 2003. I’m also very excited to have the privilege of visiting Porer and Pinbin in their home and meeting their families and community – joining the loop of one smaller circle of friendship and exchange and hopefully spiralling out into some larger ones that will continue into the future.

Ending an era, beginning a new chapter

October 20, 2012 by Giles Lane · Comments Off on Ending an era, beginning a new chapter

Its been 12 years since we published Performance Notations, the first series of Diffusion eBooks, and launched our unique publishing format on an unsuspecting world. In that time, we have commissioned and facilitated hundreds of original eBooks and StoryCubes by an incredibly diverse range of people from all kinds of disciplines and backgrounds. In that time we also began to evolve our own free and online software platform for people without professional design skills to be able to create their own eBooks and StoryCubes. Our first proof of concept prototype was made in the summer of 2003. We then spent a few years building a fully working version – the Diffusion Generator – which was online between 2006 and 2009. In September 2009 we launched bookleteer, a whole new set of ways for making and sharing eBooks and StoryCubes.

A New Place for Future eBooks & StoryCubes

This summer we made a series of technical changes to bookleteer that allow users to share their own publications directly with others via a Public Library. Each user has their own personal profile page listing all their shared publications (for instance, here’s mine) and each publication has its page listing both the downloadable PDFs and the bookreader online version (for example, see Material Conditions: Epilogue). We have further exciting developments in the pipeline too.

To continue our long tradition of commissioning and publishing new work, we have created a new Curated by Proboscis library which will, from now on, be where all new commissions and featured eBooks and StoryCubes will be listed. Our long-serving Diffusion Library website will remain online indefinitely as an archive of more than 12 years of pushing the boundaries of what we think of as publishing and creative practice.

As part of these changes we are also launching a new monthly publication – the Periodical – which will select, print and send out to subscribers some of the most exciting, experimental, imaginative and insipring eBooks created and shared on bookleteer. Anyone can take part – just sign up, make and share something on bookleteer. Each month we’ll pick one eBook to print and send out. We are also devising special projects, like Field Work, that will enable people to participate in other ways. And we are developing partnerships and collaborations to commission new series that will also be distributed as part of the Periodical’s monthly issues.

Subscribe to the Periodical and get bookleteering!

Field Work and the Periodical

September 26, 2012 by Giles Lane · 1 Comment

Publishing remains at the heart of Proboscis. We began 18 years ago with COIL journal of the moving image and followed this with many series of Diffusion eBooks. Since 1994, we have commissioned and published works by hundreds of different people in many formats.

Our latest publishing venture, the Periodical, aims to re-imagine publishing as public authoring – a phrase we’ve been using for over 10 years to describe the process by which people actively make and share what they value – knowledge, skills, experiences, observations – those things we characterise as Public Goods. Based on bookleteer, the Periodical is a way for people to participate in publishing as well as reading – in addition to receiving a printed eBook (sometimes more than just one) by post each month subscribers are encouraged to use bookleteer to make and share their own publications, which may then be chosen to be printed and posted out for a future issue.

Our first project being developed as part of this venture is Field Work : subscribers will be sent a custom eNotebook to use as a sketch and note book for a project of their own. Once they’ve filled it in they can return it to us to be digitised and shared on bookleteer. Several times a year we will select and print someone’s Field Work eNotebook to be sent out as part of a monthly issue of the Periodical.

Why are we doing this? We’ve long used the Diffusion eBook format to make custom notebooks for our projects and digitised them as part of our shareables concept. We think that such new possibilities of sharing our creative and research processes with others is a key strength of what these hybrid digital/physical technologies offer. Creating a vehicle, via the Periodical, for others to take part in an emergent and evolving conversation about how and why we do what we do seems like a natural step forward. If you’d like to take part, subscribe here.

We Are All Food Critics – The Reviews

July 6, 2012 by Giles Lane · 1 Comment

One of the most fun things we’ve done this year has to be the little project we ran as part of the Soho Food Feast : helping some of the children of Soho Parish Primary School produce their own reviews of the amazing foods on offer in specially designed eNotebooks. The children would choose something from one of the many stalls, bring it to be photographed and a Polaroid PoGo photo sticker printed out an stuck into one of the eNotebooks, then they’d write about what the dish looked, smelt, felt, sounded and tasted like. This idea of doing the reviews through the 5 senses, along with the great introduction, was contributed by Fay Maschler, the restaurant critic of the London Evening Standard and one of the Food Feast committee members.

We’ve now published a compilation of the best reviews which is available via the Diffusion Library as downloadable eBooks and in the bookreader format. We’re also printing a short run edition which will go the children themselves (and a few for the school to sell to raise funds – get one while you can!). Thanks to everyone who took part in this project – the children of Soho Parish and Soho Youth, members of the Food Feast Committee (Anita Coppins, Wendy Cope, Clare Lynch), Rachel Earnshaw (Head Teacher) and the team here : Mandy Tang, Haz Tagiuri & Stefan Kueppers.

Neighbourhood knowledge in Pallion

July 2, 2012 by Giles Lane · Comments Off on Neighbourhood knowledge in Pallion

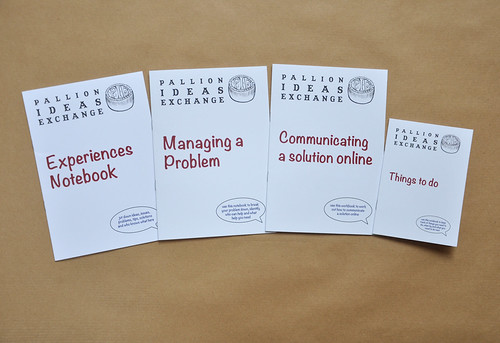

Last Thursday I visited members of the Pallion Ideas Exchange (PAGPIE) at Pallion Action Group to bring them the latest elements of the toolkit we’ve been co-designing with them. Since our last trip and series of workshops with them we’ve refined some of the thinking tools and adapted others to better suit the needs and capabilities of local people.

Pallion Ideas Exchange Notebooks & Workbooks by proboscis, on Flickr

Using bookleteer‘s Short Run printing service we printed up a batch of specially designed notebooks for people to use to help them collect notes in meetings and at events; manage their way through a problem with the help of other PAGPIE members; work out how to share ideas and solutions online in a safe and open way; and a simple notebook for keeping a list of important things to do, when they need done by, and what to do next once they’ve been completed.

We designed a series of large wall posters, or thinksheets, for the community to use in different ways : one as a simple and open way to collect notes and ideas during public meetings and events; another to enable people to anonymously post problems for others to suggests potential solutions and other comments; another for collaborative problem solving and one for flagging up opportunities, who they’re for, what they offer and how to publicise them.

These posters emerged from our last workshop – we had designed several others as part of process of engaging with the people who came along to the earlier meetings and workshops, and they liked the open and collaborative way that the poster format engaged people in working through issues. We all agreed that a special set for use by the members of PAGPIE would be a highly useful addition to their ways of capturing and sharing knowledge and ideas, as well as really simple to photograph and blog about or share online in different ways.

Last time I was up we had helped a couple of the members set up a group email address, a twitter account and a generic blog site – they’ve not yet been used as people have been away and the full core group haven’t quite got to grips with how they’ve going to use the online tools and spaces. My next trip up in a few weeks will be to help them map out who will take on what roles, what tools they’re actually going to start using and how. I’ll also be hoping I won’t get caught out by flash floods and storms again!

We are also finishing up the designs of the last few thinksheets – a beautiful visualisation of the journey from starting the PAGPIE network and how its various activities feed into the broader aspirations of the community (which Mandy will be blogging about soon); a visual matrix indicating where different online service lie on the read/write:public/private axes; as well as a couple of earlier posters designed to help people map out their home economies and budgets (income and expenditure).

Our next task will be to create a set of StoryCubes which can be used playfully to explore how a community or a neighbourhood group could set up their own Ideas Exchange. It’ll be a set of 27 StoryCubes, with three different sets of 9 cubes each – mirroring to some degree Mandy’s Outside the Box set for children. We’re planning to release a full Neighbourhood Ideas Exchange package later this summer/autumn which will contain generic versions of all the tools we’ve designed for PAGPIE as well as the complete set of StoryCubes.

3 days in Pallion

May 19, 2012 by Giles Lane · Comments Off on 3 days in Pallion

This week just passed Alice, Haz and myself have been running some co-design workshops with local community members in Pallion, a neighbourhood in the city of Sunderland, and with Lizzie Coles-Kemp and Elahe Kani-Zabihi of Royal Holloway’s Information Security Group, hosted at Pallion Action Group. The workshops, our second round following some others in early April, were focused around visualising the shape, needs and resources available to local people in building their own sustainable knowledge and support network – the Pallion Ideas Exchange. We also worked on testing the various tools and aids which we’ve designed in response to what we’ve learned of the issues and concerns facing individuals and the community in general.

The first day was spent making a visualisation of the hopes and aspirations for what PIE could achieve, the various kinds of activities it would do, and all the things they would need to make this happen. Based on previous discussions and workshops we’d drawn up a list of the kinds of activities PIE might do and the kinds of things they’d need and Mandy had done a great job over the past couple of weeks creating lots of simple sketches to help build up the visual map, to which were added lots of other issues, activity ideas, resources and hoped for outcomes.

Visualising PIE this way allowed for wide-ranging discussions about what people want to achieve and what it would need to happen – from building confidence in young people and the community more generally, to being resilient in the face of intimidation by local neer-do-wells. Over the course of the first afternoon the shape changed dramatically as the relationships between outcomes, activities, needs, people and resources began to emerge and the discussion revealed different understandings and interpretations of what people wanted.

On the second day we focused on the tools and aids we’ve been designing – a series of flow diagrams breaking down into simple steps some methods for problem solving, recording and sharing solutions and tips online, how to promote and share opportunities to people they would benefit and things to consider about safety and privacy before posting information online. We’ve also designed some simple notebooks with prompts to help do things like take notes during meetings and at events, a notebook for breaking problems down into small chunks that can be addressed more easily alongside place to note what, who and where help from PIE is available, and a notebook for organising and managing information and experiences of PIE members about sharing solutions to common problems that can be safer shared online. As the props for a co-design workshop these were all up for re-design or being left to one side if not relevant or useful. An important factor that emerged during the discussion was that people might feel uncomfortable with notes being written in a notebook during a social event – the solution arrived at was to design a series of ‘worksheet posters’ which could be put up on the walls and which everyone could see and add notes, ideas or comments to. The issue of respecting anonymity about problems people have also led to the suggestion of a suggestions box where people could post problems anonymously, and an ‘Ideas Wall’ where the problems could be highlighted and possible solutions proposed. We came away with a list of new things to design and some small tweaks to the notebooks to make them more useful – it was also really helpful to see a few examples of how local people had started using the tools we’ve designed to get a feel for them:

On the afternoon of the second day we also spent a long time discussing the technologies for sharing the community’s knowledge and solutions that would be most appropriate and accessible. We looked at a whole range of possibilities, from the most obvious and generic social media platforms and publishing platforms to more targeted tools (such as SMS Gateways for broadcasting to mobiles). As we are working with a highly intergenerational group who are forming the core of PIE (ages range from 16 – 62) there were all kinds of fluencies with different technologies. This project is also part of the wider Vome project addressing issues of privacy awareness so we spent much of the time considering the specific issues of using social media to share knowledge and experiences in a local community where information leakage can have very serious consequences. Ultimately we are aiming towards developing an awareness for sharing that we are calling Informed Disclosure. Only a few days before I had heard about cases of loan sharks now mining Facebook information to identify potential vulnerable targets in local communities, and using the information they can glean from unwitting sharing of personal information to befriend and inveigle themselves into people’s trust. The recent grooming cases have also highlighted the issues for vulnerable teenagers in revealing personal information on public networks. Our workshop participants also shared some of their own experiences of private information being accidentally or unknowing leaked out into public networks. At the end of the day we had devised a basic outline for the tools and technologies that PIE could begin to use to get going.

Our final day at Pallion was spent helping the core PIE group set up various online tools : email, a website/blog, a web-based collaboration platform for the core group to organise and manage the network, and a twitter stream to make announcements about upcoming events. Over the summer, as more people in Pallion get involved we’re anticipating seeing other tools, such as video sharing, audio sharing and possibly SMS broadcast services being adopted and integrated into this suite of (mainly) free and open tools.

The workshops were great fun, hugely productive but also involved a steep learning curve for all of us. We’d like to thank Pat, Andrea, Ashleigh and Demi (who have taken on the roles of ‘community champions’ to get PIE up and running) for all their commitment and patience in working with us over the three days, as well as Karen & Doreen at PAG who have facilitated the process and made everything possible. And also to our partners, RHUL’s Lizzie and Elahe who have placed great faith and trust in our ability to devise and deliver a co-design process with the community that reflects on the issues at the heart of Vome.

City As Material 2 with Professor Starling of DodoLab

February 28, 2012 by Giles Lane · 3 Comments

Once again we have been collaborating with our esteemed colleagues Andrew Hunter and Lisa Hirmer at DodoLab on a discursive exploration of place and knowledge as part of our ongoing investigations and collaborative publishing project, City As Material. This time we have been undertaking a research expedition with Professor William Starling into the decline of the European Starling in Britain, seeking stories and evidence to explain their rapid disappearance in three towns : Thetford (in Norfolk), London and Oxford. Alongside Proboscis and DodoLab, we were accompanied by expedition members Dr Josie Mills, Curator of the Art Gallery at the University of Lethbridge, Canada and artist Leila Armstrong.

Haz has posted reports for each of the journeys and visitations which we undertook in Thetford, London and Oxford over on our bookleteer blog and we are now collaborating to produce a series of eBooks charting the expedition’s activities and findings – blending together questions, observations, musings, photos, drawings, rubbings and other things collected. As before, we’ll print up a limited edition of the books as well as placing downloadable PDFs in the online Diffusion Library for handmade versions and enabling bookreader versions for reading online.

bridging the digital/physical divide

October 14, 2011 by Giles Lane · 1 Comment

A few days ago we deployed a simple but exciting design change to bookleteer.com, namely we have added QR Codes and Short URL links to every Diffusion eBook’s back page. These link directly to the online bookreader version of the eBook – a web-based version that makes it possible to read the eBooks directly on mobile devices such as smartphones (Android, iPhone, Blackberry etc), tablets (iPad, Galaxy tab etc) or any computer.

What’s so exciting about that you may ask? Well, we have been thinking about ‘tangible souvenirs‘ for a few years now – exploring ways of capturing and sharing aspects of ‘digital experiences’ into physical forms such as the Diffusion eBooks and StoryCubes. This might be data visualisations or digital assets such as photos, tweets etc arranged to act as mementoes of ephemeral experiences which are primarily mediated through digital technologies. Conversely we have also been thinking about how to share these ‘tangible souvenirs’ digitally as well as physically. This thinking originated in a small project we helped take place between schoolchildren in a village in rural Nigeria making and sharing eBooks with schoolchildren in Watford, north London. In parts of Africa computers, printers, paper and internet access were (and remain) scarce – yet mobile phones were proliferating fast. If people who had never before had access to low cost publishing technologies through the simple tools we had created (Diffusion eBook format and bookleteer.com) could use these to publish their own knowledge and experiences how then would they share them when the means of production (computers, printers, paper etc) which we take for granted in the industrialised world, were still scarce?

The answer was to find another bridge between the digital and the physical – enabling people to share their Diffusion eBooks not only through the PDF files and printed formats, but also via mobile phones. In 2007 I wrote a post on diffusion.org.uk (our free library of eBooks and StoryCubes) speculating on how we might in future use visual barcodes to make sharing the eBooks simpler. At that time we didn’t have the online bookreader format, so there was still the problem of how someone with a mobile phone could print out and read the book. However, with the implementation of bookreader (a fantastic piece of open source software created by the Internet Archive) we have been able to realise this in a remarkably simple but potentially crucial way. If someone has a printed or handmade copy of a Diffusion eBook then they can share its content with anyone else simply by letting them use their mobile device to scan the QR code (there are multiple free QR readers for most types of phone or tablet device). Or they can take a photo of the back page and email it or send it via MMS to someone who can then scan it in themselves.

By placing the Short URL link alongside the QR code we have also provided a human-readable alternative to the QR code. This way anyone can simply type the URL into a web browser on any internet-connected device to begin reading the eBook. The URLs are also short enough to send via SMS, Twitter or any other social messaging system.

Over the years we have described the concept behind the hybrid digital/physical nature of Diffusion eBooks and StoryCubes as being about creating ‘Shareables‘ – things which can float between these states, which can exist in more than one place at a time as both physical and digital objects. We have collaborated with friends, colleagues and partners to explore the affordances of capturing unique handwritten and handmade books and StoryCubes and being able to share them directly with others, almost without restriction. This simple addition linking the physical PDF/printed versions to their online bookreader versions amplifies this rippling effect between the physical and the digital in ways we can only begin to imagine.

We think this could be a step change in the uses and usefulness of bookleteer.com and the Diffusion eBook format – we’d love to hear what other people think too.

Visual Essay – Mapping

July 14, 2011 by elenafesta · Comments Off on Visual Essay – Mapping

“Space is a part of an ever-shifting social geometry of power and signification”, this is an inspiring quotation drawn from Doreen Massey’s Space, Place and Gender and immediately it puts light on two major ideas underpinning the understanding of space: its non-neutral and non semantically univocal essence, and its intrinsic conflict. Space harbours a wide spectrum of semantic nuances and potential political definitions and thus produces continual challenges in terms of interpretation and agency. “The map is not the territory”, even if it is thought to be so, but an interpretation, a graphic and linguistic exposition of a portion of territory and how ever it strains to be scientifically irrefutable, the discursive component shines through mainly in the very moment such codes are disrupted. The elaboration of alternative maps make overt that “maps, like art, far from being a transparent opening to the world, are but a particular human way of looking at the world”. The idea of embracing alternative tube maps came to my mind because I was already familiar with Alex Roggero’s Underground to Everywhere map where he replaced the tube stations with the immigrants’ city according to the main ethnic minority living in a specific area. This travel book is in every aspect an homage to the author’s wanderings across the city and a sincere admiration to the vibrant, Babylonic and multicultural London. The author himself mentions several alternative tube maps which have been produced during the years. The tube map itself is not scientifically accurate but it was designed in such a way, so readable and clear, that has become hugely popular and iconic. Moreover, a recent visit to the Museum of London gave me the idea to insert in my visual essay some samples of hand-drawn maps which are displayed at the museum entrance in order to further underline the discursive, subjective aspect of the act of mapping. In partnership with Londonist, readers were encouraged to submit hand-drawn maps, focussing on their own experiences and connections with certain areas of London and obviously the aim was not to provide a factual representation of the city but to capture the different and variegated personal projections on the cityscape. The galleries themselves, which go through London’s history from when London was just a piece of desert land to the very present, are full of fascinating maps, each revealing a peculiar sphere of London according to the point of view and the intention of the composer. Booth’s poverty maps, based on his survey into life and labour in London from 1886 to 1903, assess varying levels of indigence and criminality in different districts across London, graphically accessible through a colour code, so for example, dark blue stands for ‘Very poor. Casual, chronic want’, while black stands for ‘Lowest class. Vicious, semi criminal.’ The textual level of the mapping process discloses diverse perspectives on the emotional and biased degree involved in any act of representation and this leads us to think that the entity represented, in this case the city of London or at least a portion of it, is to be found where more or less codified and official discourses and a multitude of singular experiences meet. Regarding this, it is very illuminating to address Proboscis’ Urban Tapestries project which, combining mobile and internet technologies with geographic information systems, looked at how people could actively map the environment around them and earnestly share this ever-evolving body of knowledge. This kind of collaborative mapping hints at another aspect implicit in the mapping process: its blatant lack of innocence suggests a potential political use, either as a tool of coercion and possession – unequivocal, for instance, is the case of Imperialism as Edward Said suggests – and as an instrument to reclaim and re-conquer one’s own right to the city and to build an alternative organic mutuality.

I see mapping as a central issue in Proboscis’ work not only because several projects have focussed on contemporary perceptions of the human, social and natural landscape around us – see for example the Liquid Geography ebooks series – as well as on fertile and rewarding ways to affect it, but their general conceptualization follows the mapping procedure. Proboscis’ approach simulates an unexpected plot, a thorough exploration, rich in ramifications, bends and junctions, sudden and unpredictable directions.

Bookleteer’s new web bookreader

June 11, 2011 by Giles Lane · Comments Off on Bookleteer’s new web bookreader

This year’s seen several major milestones achieved in developing our bookleteer platform. At the beginning of the year we launched a User API (Application Programming Interface) allowing people to create and share eBooks and StoryCubes directly from their own projects, applications and websites.

In February we unveiled a new price estimator to help people calculate the costs of printing and shipping (all over the world) eBooks and StoryCubes through our Short Run Printing Service. We combined this with new pricing structures that make both the eBooks and StoryCubes cheaper and easier to order in small quantities (from 50 copies)

This month we’ve launched what we think is our most exciting new feature : an online bookreader allowing users to read and share their eBooks via standard web browsers. We have also re-vamped the user interface for creating and editing eBooks which should make it simpler and more intuitive. Below is an example of an embedded ‘mini reader’ showing an eBook created by Caroline Maclennan as part of Alice’s As It Comes project in Lancaster:

You can also find plenty more (and growing) over on our Diffusion website.

Telling Worlds by Frederik Lesage

April 20, 2011 by admin · Comments Off on Telling Worlds by Frederik Lesage

Telling Worlds

A Critical Text by Frederik Lesage