Outside The Box – First Play Test

April 18, 2011 by mandytang · 2 Comments

Hi all! We had our first play test for Outside The Box yesterday with the children who were taking part in the play scheme with the YMCA of Central London. We went with them to Lambourne End Centre for Outdoor Learning, where the children will get to take part in various activities including a chance to have a go with the play sets.

Upon arrival I was engulfed by the surrounding greenery, the centre was huge! 54 acres of land; open fields with animals grazing on the grass and various adventure activities built and scattered across the vast fields.

As we walked through the reception area to catch up with the children who were currently having lunch. My attention was immediately swept away from a beautiful blond haired horse which trotted passed; a small carriage trailing behind it with children gleefully cheering as they enjoyed the ride, “I want to go on that” was all I could think of after that.

After lunch the children were split into two groups and thus it was time to set the cubes free onto the grass and just see what happens.

The curious children watched and questioned as Giles placed the play set on the grass, they began picking them up and marvelled at the different drawings and asked who drew them – I felt proud and happy that they really liked them. They’ve ask me how did I draw the images to which I explained very briefly the process.

Then the blank cubes had become like gold, they all became immersed in the idea of making their own cubes and swarmed around trying to overcome the challenge of assembling a cube and immediately attacking the art box soon after. Frantically scooping PVA glue over the grass and dribbling it across each other, they busied away crafting their masterpiece.

There was one girl however, who was more determined to solve the animal set. At first when she couldn’t work it out she claimed the cubes were wrong, so I nudged and gave a clue to which she immediately thought “Ah! so it can also go this way!” she shuffled the cubes and tried again. Eventually she solved the puzzle and huffed “that was hard”.

Then the groups switched over, a trio sprinted across the field and sat down to make a cube. They then began playing with the storytelling set. At first they only picked one word from each face of the cube – which made their stories one sentence long, but after suggesting that they can use all the words from each face, their stories became longer.

One of the girls used the words in order shown, another used the genre cube – but instead of rolling it she preferred to choose the face that she liked and did the same with the word cubes. They competed with each other to tell the best story and started shouting to drown out each other’s story!

(If you would like to listen to some of their funny stories, click on the links below)

http://audioboo.fm/boos/329978-stories-from-storycubes

http://audioboo.fm/boos/329979-more-stories

Finally the groups reunited to go see the farm animals, indicating the end of the first play testing session. Overall it was a great opportunity to be able to play test with children in a outdoor setting, it gave me an idea of what needs changing and how to set up the next play test. It would have been better to be able to get more children to play with them and to also get some of the boys to give it a go for a fair play test, instead of taking one look at it and tossing it aside for football. I thank the Central YMCA for this opportunity and look forward to more visits in hope that children will like Outside The Box. As for the golden horse that kept trotting passed me numerous times and swaying it’s golden mane as if taunting me…one day..one day..*shakes fists*.

Outside The Box eBooks

March 15, 2011 by mandytang · 1 Comment

(Drum rolls) Ladies and Gentlemen, I proudly present the finished eBooks!

The eBooks are part of Outside The Box and were created to accompany the play sets, they act as props to help stimulate game play.

I’ve created a total of six eBooks that fit with the role playing set, each eBook corresponds to the six roles available. Once roles have been assigned, players can take their eBooks with them to carry out missions. They can use it to take notes, draw maps, sketch images or even stick things into, they can do whatever they like with these eBooks that will assist their game experience.

But what’s inside you ask? (sniggers). Each book is themed to each role, not just on the cover, but the inside pages too. All pages inside are hand drawn with blank spaces for the player to use, it’s printer friendly and encourages players to freely scribble in them.

The eBooks can also be used for the other play sets too! For example, players can choose an eBook of their choice and use it to play along the story telling game. Or they could use the eBooks to create strange combination animals. (More suggestions available in the Outside The Box Suggestion eBook).

I enjoyed designing and creating the eBooks, it all began with making miniature versions as the initial design. Then making the basic prototype and moving onto finalising details and adding messages to the players. I had a lot of fun making the eBooks, I now hope that players will enjoy the finished product.

Outside The Box – First Full Draft

January 19, 2011 by mandytang · 2 Comments

It took a bit longer than planned, but the set of cubes for Outside The Box have reached the first prototype stage! (Applauds) It took a lot of energy to meet the deadline but seeing the finished prototype makes all the hard work worthwhile, I am very pleased with the results and hope you all will grow fond of them too! Thank you Giles and Alice for your patience and advice in teaching me the palette decision making process and guiding me in polishing the sets to a finished prototype. Thanks to Radhika and Haz for taking time out to assist in assembling the cubes together and working on the story telling set!

What happens next? (grin) we play with them! The next stage will be to test them out, not just with the team but with our target audience – kids! We’ll be thinking of additional ways to play with them, making observations to check that children understand the content on the cubes and hope they will enjoy playing with them. Our findings in this stage will be taken into consideration when making decisions on the final product.

Outside The Box – Progress

December 16, 2010 by mandytang · 1 Comment

Outside The Box is a project inspired by the Love Outdoor Play campaign, which supports the idea of encouraging children to play outdoors. We brainstormed about possible games children could play and creating props to assist their gameplay using Diffusion eBooks and StoryCubes made with bookleteer.

The first idea was a visual game using the StoryCubes, which Karen had blogged a sneak peek of a few weeks back. It was a brain teaser type of game, where one image was spread across two squares – so one face of the cube had 4 halves of an image along each edge of the square. The aim was to match up the top and bottom half together. The puzzle only worked if there was nine squares, any less and it wouldn’t have been challenging enough.

The original set had 4 themes, the first being domestic pets, the second insects and bugs, the third sea creatures and the fourth snakes.

After leaving this set out for members of Proboscis to try and solve, they thought it was humorous mismatching the animal halves together. They came up with many wild combinations such as a mer-dog (top half of a dog and lower half of a fish) which struck the idea of another way to play with this set of cubes – make the sound of the animal on the top half and move like the animal on the bottom half. Keeping this idea in mind, I redeveloped the set by adding different animals which make funny noises or move differently and as a result it made the puzzle easier for a younger age group because it resembled the card game Pairs.

The next set consists of a role playing game, encouraging children to use their imagination and interacting with each other if played in groups. With elements of exploration, this set was most fitting for the Love Outdoor Play campaign. There are six characters to choose from, each occupying one face on each cube with a mission. Just like the first set, this game used a total of nine cubes – meaning each character had a total of nine missions to accomplish. Characters for this set included spy, detective, super hero, storyteller, adventurer and scientist.

The last set is a story telling game, the set of cubes acts as a starting point in telling a story leaving children to fill in the gaps with their imagination. One cube decides the genre of the story, another cube decides the time setting and a third cube decides how the story will be told. Keeping the consistency of using nine cubes in one set, the remaining six cubes consists of words to which the player will use in their story.

At the moment these games are in prototype stage, where the final colour palette is to be decided and the finishing touches to be made and polished. Although I had hoped to have finished the prototypes sooner I guess working on 162 faces was a lot more challenging than I thought (laughs). 120 of the faces were illustrated and the remaining 42 contained words, which the Proboscis team kindly assisted with (thanks everyone!) Nonetheless, I have enjoyed the whole process and think that this project has given the opportunity for team work and I still feel that I have much to learn and look forward to learning more about the different methods used in deciding a colour palette for the final product.

StoryMaker PlayCubes

November 16, 2013 by Giles Lane · 4 Comments

StoryMaker is a set of 9 playcubes (1 of 3 sets from Outside The Box) that incite the telling of fantastical tales. Roll the three control cubes to decide how to tell your story, what kind of story it should be and where to set it. Then use the six word cubes as your cue to invent a story on the spot. Each set comes flatpacked with a PlayGuide booklet. You can browse all the cubes and the play guide on bookleteer.

Make up stories on your own or with friends. Challenge your storymaking skills with the Genre, Context and Method cubes to suggest what type of story you can tell, what time or place it is set in and how you’re going to tell it. Use the Word cubes to make the game even more fun: choose one set of words to tell you story with, or combine different sets to make up longer stories or more complex games.

Earlier this year we printed up a small edition of the StoryMaker PlayCubes which are now available to purchase. If you’d like a set then please order below or visit our web store for other options.

|

StoryMaker PlayCubes Set

9 PlayCubes + PlayGuide Booklet |

||

|

United Kingdom

|

European Union

|

USA/Rest of the World

|

|

£25

(inc VAT & p+p) |

£30

(inc VAT &p+p) |

£35

(inc p+p) |

|

use PayPal below

|

use PayPal below

|

|

|

Pay with Paypal

|

||

PlayCubes : kickstarting the next stage

October 29, 2013 by Giles Lane · 1 Comment

Three years ago, not long after Mandy Tang started at Proboscis, we came up with an idea to use the StoryCubes and bookleteer to inspire people to play and invent their own games. We were inspired ourselves by the Love Outdoor Play campaign, which aims to encourage children, and their parents, to play outside more. Over about six months Mandy developed Outside The Box as a side-project within the studio, devising the three games with help from the team and illustrating all the resulting cubes. We frequently got together to test out the game ideas, as well as with friends and eventually with a group of children on a YMCA play scheme. But as the studio got stuck into several large projects, we didn’t get round to completing the whole package until recently.

The result is Outside The Box – a “game engine for your imagination” – designed to inspire you to improvise and play your own games on your own or with others, indoors or outside. It’s made up of 27 cubes, 3 layers of 9 cubes, each layer being a distinct game : Animal Match, Mission Improbable and StoryMaker. Outside The Box has no rules, nothing to win or lose, the cubes simply provide a framework for you to imagine and make up your own games. You can browse through the whole OTB collection of cubes and books on bookleteer, to download and make up at home.

However, 27 large PlayCubes and 7 books is a lot to make yourself, so we’re now planning to manufacture a “first edition” to get them into people’s hands to find out what they do with them. To achieve this we’re running a kickstarter campaign to raise funds – support the project to get your own set in time for Christmas or choose other rewards.

- Mission Improbable

- StoryMaker

- Animal Match

Animal Match starts out as a puzzle – match up the animal halves to complete the pattern. From there you can make it much more fun : mix the cubes up to invent strange creatures; what would you call them? What would they sound like? How might they move?

Mission Improbable is for role-playing. There are 6 characters: Adventurer, Detective, Scientist, Spy, Storyteller and Superhero, each with 9 tasks. Use them to invent your own games, record your successes in the mission log books or take it to another level by designing your own costumes and props.

StoryMaker incites the telling of fantastical tales : Roll the 3 control cubes to decide how to tell your story, what kind it should be and where to set it. Then use the word cubes as your cue to invent a story on the spot.

Neighbourhood knowledge in Pallion

July 2, 2012 by Giles Lane · Comments Off on Neighbourhood knowledge in Pallion

Last Thursday I visited members of the Pallion Ideas Exchange (PAGPIE) at Pallion Action Group to bring them the latest elements of the toolkit we’ve been co-designing with them. Since our last trip and series of workshops with them we’ve refined some of the thinking tools and adapted others to better suit the needs and capabilities of local people.

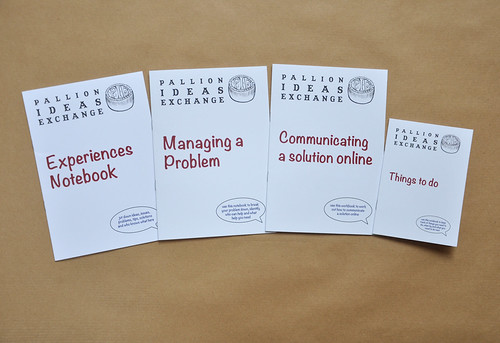

Pallion Ideas Exchange Notebooks & Workbooks by proboscis, on Flickr

Using bookleteer‘s Short Run printing service we printed up a batch of specially designed notebooks for people to use to help them collect notes in meetings and at events; manage their way through a problem with the help of other PAGPIE members; work out how to share ideas and solutions online in a safe and open way; and a simple notebook for keeping a list of important things to do, when they need done by, and what to do next once they’ve been completed.

We designed a series of large wall posters, or thinksheets, for the community to use in different ways : one as a simple and open way to collect notes and ideas during public meetings and events; another to enable people to anonymously post problems for others to suggests potential solutions and other comments; another for collaborative problem solving and one for flagging up opportunities, who they’re for, what they offer and how to publicise them.

These posters emerged from our last workshop – we had designed several others as part of process of engaging with the people who came along to the earlier meetings and workshops, and they liked the open and collaborative way that the poster format engaged people in working through issues. We all agreed that a special set for use by the members of PAGPIE would be a highly useful addition to their ways of capturing and sharing knowledge and ideas, as well as really simple to photograph and blog about or share online in different ways.

Last time I was up we had helped a couple of the members set up a group email address, a twitter account and a generic blog site – they’ve not yet been used as people have been away and the full core group haven’t quite got to grips with how they’ve going to use the online tools and spaces. My next trip up in a few weeks will be to help them map out who will take on what roles, what tools they’re actually going to start using and how. I’ll also be hoping I won’t get caught out by flash floods and storms again!

We are also finishing up the designs of the last few thinksheets – a beautiful visualisation of the journey from starting the PAGPIE network and how its various activities feed into the broader aspirations of the community (which Mandy will be blogging about soon); a visual matrix indicating where different online service lie on the read/write:public/private axes; as well as a couple of earlier posters designed to help people map out their home economies and budgets (income and expenditure).

Our next task will be to create a set of StoryCubes which can be used playfully to explore how a community or a neighbourhood group could set up their own Ideas Exchange. It’ll be a set of 27 StoryCubes, with three different sets of 9 cubes each – mirroring to some degree Mandy’s Outside the Box set for children. We’re planning to release a full Neighbourhood Ideas Exchange package later this summer/autumn which will contain generic versions of all the tools we’ve designed for PAGPIE as well as the complete set of StoryCubes.

Final impressions – Radhika Patel

June 23, 2011 by radhikapatel · Comments Off on Final impressions – Radhika Patel

Marketing Assistant

(6 Month Placement, Future Jobs Fund November 2010-April 2011)

The past six months have absolutely flown by! Now that I have come to the end of my placement here at Proboscis, I thought I’d take a look back at my time here.

I have been fortunate enough to be involved in quite a few projects in the past six months. As I mentioned in my previous posts, I started off by launching the StoryCube website and have continued to blog weekly on different uses for the StoryCubes as well as including a feature post series about selected StoryCube sets. As I became a more confident blogger, I also started to blog on the Bookleteer blog about the different uses and recently moved onto blogging about my love of fashion and photography with publishing.

Taking part in Mandy’s Outside the Box project was great fun as all the team members got involved. I was mainly involved in the brainstorming part, thinking of different suggestions of ways the game can be played, as well as coming up with numerous words for one of the layers of the game.

I also got to do some photography (unexpectedly) in the studio, usually for documentation purposes. This led onto doing the photography for Alice at the 50’s Fashion Exhibition, which was a great experience, as I have not done something like that before, but would love to continue doing it. The teaching I got from Alice and Giles about using the SLR and photography has been much more effective than any class I have attended. Thank you!

Alongside this, I have been involved in the ‘re-vamp’ of the Pitch Up & Publish sessions; trying to attract a younger demographic on a frequent basis. This is where I was really able to let me creative side run wild, creating slogans and writing copy, which I love doing. This is something I also want to pursue in the future – copywriting.

The placement has been helpful on a personal development level as well as career wise. This was a totally different sector for me to work in, and was quite challenging being put in an unfamiliar environment. However it enabled me to experience and learn new things, which I would not have if I wasn’t offered the, placement, such as the arts and culture sector.

My time at Proboscis has been great and have been lucky enough to be kept on for a few more months.

Telling Worlds by Frederik Lesage

April 20, 2011 by admin · Comments Off on Telling Worlds by Frederik Lesage

Telling Worlds

A Critical Text by Frederik Lesage

A recurring theme underpinning Proboscis’ work is storytelling. Their preoccupation with it is not only reflected in the stories they have told – through works such as Topographies and Tales and Snout – but also in their efforts to explore the practices and forms that enable people to tell stories. For a group of artists to embark on this latter kind of exploration may at first seem counterintuitive; the artist as a teller of stories is a familiar role, the artist as one who helps us tell our own is less so. It is beyond the scope of this paper to convince the reader of the value of such a role. Rather, I will set out to investigate how a specific tool developed by members Proboscis helped to shape one particular collaborative exchange with Warren Craghead in a work titled A Sort of Autobiography. By doing this, I hope to demonstrate how collaborative processes for storytelling like the ones that Proboscis are developing require new frameworks for understanding the kinds of work taking place.

What in the world is a StoryCube?

I often hear this perplexed question when talking to people about my research into Proboscis’ work. Most often, my answer is similar to the one that Proboscis themselves give on their diffusion.org.uk website:

StoryCubes are a tactile thinking and storytelling tool for exploring relationships and narratives. Each face of the cube can illustrate or describe an idea, a thing or an action, placed together it is possible to build up multiple narratives or explore the relationships between them in a novel three-dimensional way. StoryCubes can be folded in two different ways, giving each cube twelve possible faces – and thus two different ways of telling a story, two musings around an idea. Like books turned inside out and upside down they are read by turning and twisting in your hand and combining in vertical and horizontal constructions.”

This answer, for the most part, tells my interlocutor what one can do with a StoryCube – it encompasses a number of actions as part of a process wherein one makes and uses this particular type of object. The StoryCube represents a way to print images and text onto a different kind of paper surface in order to share these images and texts with others in a particular way. But I often find that this answer does not suffice. In this paper I will argue that this problem arises because, although a process description of what one can do with a StoryCube does provide part of the answer for what in the world it is, a more complete answer would require more worlds in which it has been used.

To clarify this obtuse little wordplay, I turn to two different authors who provide two very different models for understanding how culture is made and how it is interpreted: Howard Becker’s art worlds and Henry Jenkin’s story worlds.

Art Worlds

Disciplines such as the sociology of art have gone out of their way to show how artists are not alone in creating cultural objects. It has arguably become a cliché to state this fact. But one must not forget its implication. Howard Becker’s Art Worlds (1982), for example, demonstrates to what degree artistic practices from painting to rock music constitute complex sets of relationships among a number of individuals who accomplish different tasks – the people who make, buy, talk about, pack and un-pack works of art are connected through what he refers to as art worlds. These worlds are populated by different roles including artists, editors, and support personnel. By artists, he means the people who are credited with producing the work. By editors, he means the people who modify the artwork in some way before it reaches its audience. By support personnel, he means the people who help ensure that the artwork is completed and circulated between people but who aren’t credited with producing the artwork itself. This might include a variety of different people including framers, movers and audience members. If one were to apply Becker’s art world model to the world of book publishing and printing, for example, we might say that the artists are the authors, that publishers are editors and that the book printers are part of the support personnel: they reproduce and maintain a set of conventions for the production and distribution of an author’s work.

Part of Becker’s point is that even if we credit authors as the source of a book’s story, significant parts of the book’s final shape will be defined by choices that are the purview of support personnel like printers rather than by the authors: what kind of ink will be used to print the text, the weight and dimensions of the book pages, etc. These decisions, be they based on aesthetic, economic, or other considerations, can often be made without consulting authors and have a significant impact on what readers will hold and read when they get their hands on the finished product. Nevertheless, there are arguably varying degrees of importance attributed these different choices. After all, few of us read books because of the kind of ink it was printed with.

But one should also remember that the distribution of these roles within an art world is not necessarily fixed. In Books in the Digital Age, John B. Thompson writes that it was only in the past two centuries that there has been a distinction in the Western world between what a book publisher does and what a book printer does. Prior to this differentiation, the person who published a book and the person who printed it were one and the same. Just as the distribution of printing and publishing roles can change over time, the significance attributed to these roles might also change.

Becker’s art world model is useful for the answer to my initial question stated at the beginning of this paper because it is a social world model. Placing the StoryCubes into an art world allows me to populate the process answer provided above with a number of different roles:

Proboscis are the designers of the StoryCube who created it as “a tactile thinking and storytelling tool for exploring relationships and narratives”. They invite all sorts of different people from different disciplines to play an artist’s role by using the StoryCube to “illustrate or describe an idea, a thing or an action” and to “build up multiple narratives or explore the relationships between them in a novel three-dimensional way”. The results of all of these different peoples’ work are then made available in various ways to anyone interested in these relationships and narratives. These audience members are invited to “read [the StoryCube] by turning and twisting [it] in your hand and combining in vertical and horizontal constructions.” In some cases, these same audience members take-on additional support personnel roles such as “printers” when they download the StoryCube online and print and assemble it themselves.”

This newly revised version of my answer now has artists and audiences who are working with Proboscis and StoryCubes. But it still seems quite vague. What are these “relationships and narratives” that seem to be the point of making StoryCubes in the first place?

Story Worlds

The second world I turn to for putting my answer together is what I refer to as Henry Jenkins’ “story world” model. In his book Convergence Culture, Jenkins argues that a convergence is taking place between different media that is not simply due to technological changes brought about by digitisation. He believes that in order to understand the changes taking place in media, one needs to include other factors including economic pressures and audience tastes. One of the ways in which he demonstrates this is by analysing how storytellers like the Wachowski brothers developed The Matrix franchise. Jenkins argues that the brothers were not only engaged in the process of making films but that they were in fact engaged in an “art of world building” (116) in which the “artists create compelling environments that cannot be fully explored or exhausted within a single work or even a single medium” (ibid). The Matrix was not only available as a movie trilogy but was also explored and developed in short films, comics and novels by a number of different contributing artists. In other words, today’s creative people – be they individual artists or media conglomerate business executives – need to start to think about a ‘story world’ that is manifested in multiple, interdependent media.

I would argue that one should not interpret Jenkins’ model as suggesting that story worlds exist independently of any specific medium. Rather, the model suggests that other people, not just the author credited with originating the story world, can contribute to the development of a story world. Audience members and other authors can actively reinterpret aspects of story worlds not only through an active interpretation of the text but also by authoring their own parallel contributions. This is significant because it suggests there are contingent relations of power involved in the negotiation of the overall representation and interpretation of those same story worlds. The simplest example is how laws for copyright are employed to ensure that authors and their publishers maintain certain kinds of control over the development of story worlds.

For me to explain how Jenkins’ story world model is useful for answering my initial question will take a bit more effort. In order to fully clarify why I have gone through the trouble of bringing these two very different worlds from two very different research traditions, I will need to demonstrate how they can be combined and applied to a specific example which follows bellow. For now, however, suffice it to say that the story world model deals with meaning and how the narratives and relationships that stem from the process of making and reading StoryCubes do not appear in isolation from other related meaningful artefacts. How one interprets the meaning of a particular StoryCube is embedded within a particular set of intertextual relationships that I refer to as a story world.

We now have two different ‘world’ models for explaining what are StoryCubes:

- the art world model as a way to understand how a particular artwork is produced, distributed and appreciated through a set of interdependent roles enacted by people and

- the story world model as a way to understand how meaning can be conceived as part of a number of different texts produced by a number of different people.

A sort of printing experiment – The case of Warren Craghead

I will now examine Warren Craghead’s A Sort of Autobiography and how some critics interpreted his work as a way of illustrating how both models presented above enable me to better answer what in the world is a StoryCube. A Sort of Autobiography is a series of ten StoryCubes whose outer faces are covered by drawings of Craghead’s own making. Taken together, the ten cubes are intended to be interpreted as his “possible” autobiography – hence the title of the work. Here is a description of the work posted by Matthew J. Brady on his “Warren Peace” blog as part of a longer review of the project:

With the onset of digital comics, an infinite number of possible ways to use the medium has erupted, and even the weirdest experiments are now visible for any number of people to experience. This is great for comics fans, who can now experience the sort of odd idea that creators might not have shared with the world otherwise. Warren Craghead’s A Sort of Autobiography is a fascinating example, using the tools provided by the site Diffusion.org.uk to create a series of three-dimensional comic strips, with each in a series of ten cubes representing a moment in his life, separated by decades. Some of them seem to simply place an image on each side of the cube (with one side of each working as a “title page”), while others wrap images around the surface, and several working to make faces representing Craghead at that cube’s age. It’s a neat way to use the medium, if you can call it that.”

If we attempted to place A Sort of Autobiography in the art world model presented earlier, it would be fairly easy to follow Brady’s lead and look to comic strips as a guiding template. One could say that Craghead is the artist-author who created the work. Determining who plays this role is fairly easy because Craghead has authored a number of comic strips using a similar visual style. Things get a bit more complicated when we try to determine who is the editor-publisher. Based on the information I’ve been able to gather, there doesn’t seem to be anyone other than Craghead who makes editorial choices about the content of the final artwork – the style of drawing, the way in which the story unfolds, etc. There may be some “invisible”, un-credited co-editors who help Craghead with his drawing and choice of subject matter but they are not formally acknowledged and I have not tried to enquire whether or not this is the case. What is clear, however, is that Proboscis also do take-on aspects of the editor-publisher role: Proboscis commissioned the project as part of their Transformations series, the works are made available through Proboscis’ Diffusion website and, of course, Proboscis designed what Brady refers to as the “tools” used to publish the project.

It is this last aspect that seems particularly problematic for Brady. If we focus (rather narrowly) on some of the comments Brady makes in passing about the StoryCubes as a support for the work in his review, it is clear that they make it more difficult for him to pin down the project. Much of Brady’s review seems to implicitly be asking “Is this a comic?”. In describing the work, he uses the language of comic books to help him describe it. For example:

“Some of [the cubes] seem to simply place an image on each side of the cube (with one side of each working as a “title page”) […]”

Here Brady suggests that Craghead employs a particular convention of comics – the title page – as part of how he constructs some of his cubes. But though one of the panels located at the same place on each of the ten cubes does have writing that indicates the year and how old Craghead is at the time (ex. 1970, I am zero years old; 1980, I am ten years old; etc.), there is little to suggest that this choice is necessarily drawn from comics. This might explain why Brady puts “title page” in quotation marks. Brady seems pleased with the overall results of the project but also refrains from categorizing the result outright as a comic. Recall how he ends the paragraph I cite above with:

“It’s a neat way to use the medium, if you can call it that.”

Further along in his review of the project, Brady still seems hesitant:

“Does the whole thing work as a comic? Sure, if you want to put the work into interpreting it, not to mention the assembly time, which can make for a fun little craft project.”

One could argue that Brady may be pushing the comics category a bit: Craghead’s own website doesn’t seem to put so much emphasis on whether or not this, or any of his other projects for that matter, should be interpreted as comics. But Brady is not the only one who approaches A Sort of Autobiography in this way. Inspired by Brady’s reading, Scott McCloud – an authority on the comics medium if there ever was one – characterizes Craghead’s work as an “experimental comic”. Brady and McCloud’s categorisations of A Sort of Autobiography as a comic matter in part because it strengthens a number of associations with the comics art world. For example, if one reads A Sort of Autobiography as a reader of comics, then it does involve some additional assembly time. But what if one categorised it as part of an origami art world? Then this assembly time would be taken for granted (but Craghead’s drawings on the cubes might be interpreted as an oddity).

But Brady and McCloud are able to make this kind of association in part because they are familiar with the author’s previous work. Craghead is an established comics artist for both Brady and McCloud. It is therefore possible to compare A Sort of Autobiography to his other works. This is where I need to bring in the second world model presented above – the story world. As stated previously, the definition of story worlds based on Jenkins’ work depends on a set of possible meanings within “environments that cannot be fully explored or exhausted within a single work or even a single medium”. One could argue, that Craghead creates a similar kind of story world based on a particular style of illustration and subject matter that is consistent with other works he has created. So rather than working with comparisons to other comics, Brady’s reading can simply refer to Craghead’s established story world.

But instead of placing Craghead’s biography as the foundation of our story world, why couldn’t we instead use the StoryCube’s story as our starting point? That is, rather than assuming that authors are the only ones who create meaning by telling stories, what if we assumed that Proboscis had designed a compelling story environment “that cannot be fully explored or exhausted within a single work” and that Craghead’s A Sort of Autobiography was only one of the many parallel contributions to the meaning of this medium?

This kind of inversion is problematic because our contemporary culture, for the most part, depends on consistent formal conventions to be able to make comparisons and value judgments. That isn’t simply at the level of individual artists, but as a whole. Jenkins’ story world model does allow for all sorts of different media, but most of the media he discusses are based in familiar art worlds – comics, books, television programmes, videogames, and movies – art worlds whose implicit formal conventions allow authors to tell their stories in relatively unproblematic ways. But if we don’t know what a StoryCube is, how are we supposed to know what these conventions are? How can we know if this is a “good” or “bad” StoryCube since most of us don’t know how a StoryCube is supposed to work

I would therefore argue that Craghead, Brady and McCloud are telling us their stories of the StoryCube that involves mixing together art world and story world. They are using the more or less familiar narrative of how one makes and reads comics to tell us how to make and read a StoryCube. Craghead is relating to us the tale of how an illustrator can assume the artist’s role in the process of making a StoryCube by making different kind of drawings on it. Brady and McCloud are producing accounts of how to be readers of StoryCubes. Just as with any other kind of story world, these contributions provide only partial insights into the whole story environment and how one might participate in its creation and extension.

Open worlds

The example of A Sort of Autobiography suggests why Proboscis’ initial definition, the one presented at the beginning of this text, was left under-developed: their objective is to develop a meaningful world in which people can tell stories – one that invites people to populate it with their own art worlds and story worlds. In order for there to be enough room for others to create and sustain this kind of world, Proboscis may have to allow the StoryCubes to remain an insufficient process and an incomplete story. But they must also continue the delicate work of articulating how this incompleteness can itself be a meaningful and fertile ground for others to complete. The bookleteer platform is arguably one step in this direction in that it is an attempt to generate an online community of people who use StoryCubes and other “Diffusion Shareables”.

In the end, the true challenge may not be whether any of the answers about “What in the world is a StoryCube?” are sufficiently clear or exhaustive, but whether or not one of them can entice you into telling your own story of the StoryCube.

Frederik Lesage, March 2011

Enabling Consequences by Fred Garnett

April 15, 2011 by admin · 1 Comment

Enabling Consequences

A Critical Text about Proboscis by Fred Garnett

Background

This is a critical text written to comment on the work of Proboscis in Public Sector Innovation with new technology from a cultural perspective. I was invited by Giles Lane to do this in late 2010 as I have followed the work of Proboscis since 2002 when I first went to a public event of theirs and have since appreciated the qualities of what they have done.

Introduction

What I have decided to do in my Critical Text, Enabling Consequences, is to look at why Proboscis’s innovations, which from my perspective are capable of widespread adoption, have been insufficiently recognised and acted upon. I think this comes from both how they are conceptualised, through a process related to obliquity and how they might be adopted as a process of generative innovation; that is as a platform innovation that begets further innovations.

Brief History of Proboscis

Proboscis are probably best known for their work, Urban Tapestries, a breakthrough project (undertaken with collaborating partners such as Hewlett-Packard Research Laboratories, Orange, France Telecom R&D UK Ltd, Ordnance Survey and the London School of Economics), designed to enable the interactive city to emerge based on the pull of the participative strategies of active citizenship rather than push strategies of advertising.

They appear to set themselves the question “how can you double your intellectual quality every 18 months”. In part this is a response to Moore’s Law that states that the power of computer processing doubles every 18 months, but turned into a cultural question. In practical terms Proboscis ask themselves “how can you innovate at all times in terms of process, documentation and ideas”. They see what they do as pre-competitive research, what Steven Johnson has recently entitled the ‘adjacent platform’ of innovation. That is a process that occurs before any practical innovation actually happens.

Public Sector Innovation

I am particularly interested in Proboscis because I was also previously involved in an innovation project in the Public Sector, Cybrarian, which also failed to be recognised at the time. Cybrarian was a prototype ‘Facebook for Civil Society’, for which we created the high-concept description of it being an ‘Amazon for e-gov’ as the term social network didn’t exist then (2002). Some of us subsequently formed the ‘public technology’ group lastfridaymob, which spent some time trying to analyse why. We concluded that government didn’t have the relevant interpretive criteria to understand that new technology, created to meet public needs, namely creative, interactive and participative, and that these were three factors that government found hard to recognize. I always saw these three qualities in Proboscis’ work.

There is a deeper problem that new technologies are increasingly interactive and smart, demonstrating participative affordances, and the political context into which they are pitched are representative and hierarchical. So to unpick this problem of public sector innovation a little more lets look at how innovation occurs in greater depth.

Innovation Modelling

A typical way of modelling the Innovation process is in what might be called the 4i model; Ideas, Invention, Innovation, Impact. This typically argues that someone, possibly a researcher, has a bright idea which they tinker away at until an invention can be developed. An invention is the first instantiation of a new innovation, it can be a mock-up, a model, a design, a drawing, but it has been produced as a one-off, or prototype, often to demonstrate the potential, or some expected quality. The difference between an invention and an innovation is money. Someone decides that the invention, either because they see the prototype or drawing or a description, is so compelling that it will be worth spending a lot of money setting up a production and distribution system so a version of the invention can be sold as a product on a large scale. This innovation process is also often divided into product push, where the new technology itself is compelling, or market-pull, where demand has been detected. In organisational terms this often reflects a distinction between the research and marketing functions in companies who are concerned with innovation, or a culture, like the USA, which sees social and cultural value in the process of innovation. Successful innovations need to bridge the gap between the qualities of supply-side technology-push, and the interest of demand side market-pull.

When Apple decided to launch the iPod – in technical terms a fairly simple device made on automated production lines in China – they also needed new software to control the iPod – iTunes – and new distribution arrangements with the entire music industry, for the music, songs and albums needed to populate their invention with resources. The music industry were the very people who felt that Napster, an early peer-to-peer forerunner of iTunes, threatened their entire industry, but Apple found powerful arguments for getting them on board, part of which was that Apple weren’t the first to market, so could respond to their needs. So the issue of turning a simple working invention like the iPod itself, into an innovation, is massively complex however compelling the product on display. All products have hinterlands, which can seriously affect the way an invention becomes an innovation and also how it becomes a universally recognised and used product or process, as digital music now is today. However we have been discussing product innovations being brought to market, whereas Public Sector Innovation is more concerned with processes that enable infrastructural development, and this requires a more pervasive model of innovation.

Steven Johnson’s Reef innovation v Market Innovation

Steven Johnson’s book Where Good Ideas Come From (2010) looks at ways in which innovation becomes adopted and contrasts the more typical 4i model discussed above, or market innovation, with what he calls reef innovation, what we might call infrastructural development. Steven Johnson is an American and writes about the US context, which is much more focused on invention overall than the UK and with a history of infrastructural developments coming through private sector activities; for example American utilities are generally private sector; gas, electricity, telephones etc. Whereas in the UK there has been a more mixed tradition of regulated private sector innovation, in the 19th Century, and state-controlled utilities, in the 20th Century. Following the privatisation policies of the 1980s and 1990s there has developed more of a regulated private-sector approach in the UK, returning somewhat to our 19th Century traditions.

Reef innovation is Johnson’s way of describing how a private sector model of development produces new infrastructure for society as a whole. This is a metaphor derived from how coral reefs accrete growth and so stay above sea level, as the volcanic rocks on which they are situated shift, in order to allow coral reef island life to flourish. He is discussing how the enabling utilities, such as communications technologies that lay beneath the functioning of everyday social life, evolve and grow. Johnson argues that society as a whole grows more through reef innovation; the slow accumulation of numerous utilities that form the infrastructure through which society functions, than through market innovation. So we need a more sophisticated view of infrastructural innovation, such as the reef model, to discuss public sector innovation.

However Johnson is writing of the American context where the accidental reef-like growth of market-tested processes of infrastructure accumulation is a useful metaphor, but it is not perhaps fully applicable in all socio-economic contexts. However with the concept of reef innovation Johnson is helpfully looking at systemic Innovation, rather than product innovation as the 4is model tends to do, and systemic innovation is particularly significant in times of systemic change, which we see now as we attempt to move to a Knowledge Economy, or the Information Society as the European Union calls it through its IST programmes for i2015 and i2020. However Systemic Innovation requires a still broader view of the transformational characteristics of systemic change.

Structural Innovation v Disruptive Innovation

Innovation that leads to transformational change is something that the economist Joseph Schumpeter (the so called “Prophet of Innovation”) writes about as he discusses the difference between Structural Innovation and Disruptive Innovation. Structural innovation is where the innovation extends existing uses of a product and should increase the numbers of users, such as lighter mobile phone handsets, whereas a disruptive innovation such as the mobile phone system itself, is one where the innovation changes how things are done, in such a way that challenges existing system processes. So transformational change, arguably a key feature of the coming Knowledge Economy in both the UK policy context and EU-IST programmes, actually requires the promotion of this disruptive innovation. At the governmental level this creates a problematic tension as governments are more interested in providing reliable infrastructure that changes little, but is increasingly used by citizens, rather than enabling systemic change through deploying new technology innovations.

Consequently government prefers to adopt disruptive technology innovations as infrastructure, such as websites, once they have attained widespread use and so can be seen as large-scale structural innovations. Thus a conundrum emerges in that technological innovation which enables often necessary social change comes in a disruptive form that is difficult for governments to deal with. However whilst governments are often interested in systemic change, say to improve social infrastructure during an age of global change and de-regulation, they are more comfortable with structural innovations which might extend their electoral support through greater use, rather than disruptive innovations which can alienate it.

Distinctive Features of the Proboscis Model of Innovation

However I think Proboscis are doing particularly interesting things in terms of innovation which don’t quite fit into any of these innovation models; reef, structural, disruptive. Firstly they are operating outside the boundaries of the 4is model, both in terms of generating ideas at the conceptual end of the process, and also in terms of offering processes of innovation at the take up end. Secondly they are developing innovations that are neither disruptive, nor structural, not least because Schumpeter’s models also emerge from an analysis of American economics. Proboscis are in the business of producing socially enabling participative innovations, which might be better described as enabling innovations, drawing their value from the degree to which they extend the affordances of the public realm.

I now want to look at three distinctive features, two intrinsic and one consequential, that can be identified in the Proboscis approach in order to examine what socially enabling participative innovations might mean in practice;

- a) Applied Heutagogy; namely thinking about projects in fresh ways before they begin, based on a guiding set of values, in terms of ‘moving criteria across contexts’ which might be described as providing an ‘ideas platform’ for thinking about innovation.

- b) Generative Innovations; creating innovative platforms that can then be used generatively to develop further uses by others in the public realm.

- c) Extending the Public Realm through Participation; the consequence of this approach to innovation, which emerges from using their models of thinking and applying their approach to public sector innovation.

Applied Heutagogy

I asked Giles if he thought his work fitted into the Blue-Sky model of thinking, which might be characterised as a model of brainstorming about what you do by removing under-pinning values that sustain the original work. It is thinking outside the box of existing limitations that is more likely to destroy the box than think of new uses for it. I suggested that we call Proboscis work ‘Pink-Sky Thinking’, meaning it was fresh but rooted in the original values that they started with. He declined to accept this and suggested that their thinking tended to be oblique. I think this is because they see their work as being of a piece and that Proboscis have extended their original vision by learning from their projects and the ways in which they have been implemented, Social Tapestries emerging out of Urban Tapestries for example.

Giles suggested that their approach was deeply rooted in their values of ‘moving criteria across contexts,’ which is the classic art school strategy of heutagogy. But Proboscis aren’t simply artistic provocateurs, they think deeper than that as their thinking is informed by a profound understanding of the public realm in which their innovations will be situated, so they are also thinking of consequences as well as creative solutions. Steven Johnson also talks of a process of moving criteria across contexts that he calls exaptation, but this is more limited than the applied heutagogy Proboscis use as it is generally the application of one new set of criteria to one new field of practice in search of innovation. Proboscis are more flexible than this, but I think they are engaged in a broader process of multiple exaptations in their thinking. This process of thinking through a multiplicity of strategies derived from a range of contexts I would characterise as an ‘ideas platform.’ This offers a richer conceptual mulch than the ‘adjacent platform’ model described by Johnson, as it is also takes account of the consequential use states and the state changes (Giles’s term) that might be enabled. It could also be described as thinking about where good ideas go to…

Generative Innovation

Kondratieff talks of long wave economic change coming from what he terms ‘meta technologies’, technologies that are embedded in other technologies like the steam engine and the microprocessor. However long-term social change comes from behavioural adaptations to the affordances of these new technologies, such as the car or the mobile phone. But social change also needs infrastructure that supports the use of the new technologies; for example, time was standardised across Britain in 1840 to meet the needs of the railways. In many ways since 1770 this infrastructure has been in the form of networks of new technologies; canals, railways, telegraph, telephone, roads, electricity, television, the Internet. However these networks have tended to be dedicated to a single mode of use until the Internet came along. Like electricity this enables it to be a multi-use network, but the Internet is also capable of supporting and distributing multiple formats. Thus across this network an almost unpredictable range of uses can be developed; the Internet enables a range of consequential uses, limited only by the design flexibility of the digital formats themselves. The World Wide Web itself is one such multi-modal consequence of the flexibility of the Internet, but it is possible to design with it’s almost endlessly consequential nature in mind and Proboscis seem cognisant of this.

A Generative Innovation might be described as an innovation that enables further innovations, as described above, not as an embedded meta technology but as a platform of possibilities. An interesting development in Proboscis work was the shift from Urban Tapestries to Social Tapestries, from a platform to a user environment and what characterises their user environments is their participative quality.

Arguably the Knowledge Economy and the Information Society are characterised by the participative qualities of the technologies used to build them, this has been particularly clear since the ‘architecture of participation’ that is Web 2.0 became widely available as a possible infrastructure platform. Proboscis’s work has anticipated this participatory quality due to the heutagogic nature of their thinking about creating generative processes. This thinking can be described as an ideas platform, which precedes the adjacent platform model of innovation as described by Johnson. Proboscis were used to playing with form, moving criteria across contexts as they describe it, at a time when new technologies capable of creating social transformation were emerging so, for them, the flexibility of digital technologies, their arguably ‘disruptive’ qualities, were already accounted for at the thinking stage.

Extending the Public Realm through Participation

So the combination of applied heutagogy and generative innovations has the Enabling Consequence of creating the possibility of extending the public realm through participation in this age of digital networks and use affordances. This is because Proboscis are engaged in flexible thinking about future possibilities whilst being aware of how implementation might extend and change the character of the public realm. They design for the participative qualities of digital networks and so capture what makes them so attractive to people in society.

[CAVEAT: I don’t want this to read like a testimonial, after all it is a critical text and not all of Proboscis’s projects have been unqualified successes, but this has been an attempt to capture both what uniquely characterises their approach and to also try and understand how public sector innovation might be made to work effectively in the UK in an age of digital flexibility.]

Conclusions; Enabling Consequences

Proboscis’ research model

Proboscis have a concern with public sector innovation in a time of digital flexibility, but are capable of absorbing the transformative potential of the evolving digital realm into both their thinking, as social artists comfortable with the heutagogic playing with form, and as visionaries, capable of thinking of how new platforms might enable greater engagement in and with the public realm. They bring this together in an unusually broad and deep way of solving problems, what I call applied heutagogy, addressing multiple perspectives not just the artistic one of playing with form.

The participative affordances of the technology and the heutagogic quality of their thinking, what they call ‘moving criteria across contexts’, combine to offer the possibility of creating generative infrastructure; infrastructure that begets further infrastructure. They work with the grain of digital transformation both conceptually and in terms of its consequences.

Public sector Innovation

Most public sector innovation emerges from a hierarchical policy process that has originated in one part of government and has a clearly defined and departmentally owned problem it wants solving. Public sector innovation typically, for a range of historical, political and cultural reasons, wants structural innovation that extends the relevance and influence of the owner of the policy and so sees innovation concerning ‘state changes’ as disruptive and out of scope.

Ben Hammersley recently highlighted this conceptual problem at the governmental level, what he characterises as the clash between hierarchical and network thinking, in his British Council lecture in Derry on March 25 2010. The problem Hammersley highlights is hierarchical thinking about networked contexts. The public sector wants innovation to be structural in order to count as improving their policy delivery in alignment with the current construction of existing policy responsibilities; it thus ignores the ‘state change’ potential offered by new network possibilities. In terms of innovation the public sector is, at best, involved in post-hoc legitimation but not in the creation of participation platforms designed to work in the emerging network contexts.

Innovation in a Transformative context

So we have an impasse; the opportunity for the development of a digitally flexible public realm capable of supporting a range of interdisciplinary models of innovation working across open networks, and a public policy context which is incapable of recognising networked and other new technology affordances. We can describe this as a clash between possible participative and traditional representative views, both of working processes and of society (and so of policy development); or more simply a clash of values. Proboscis want to ‘establish a discourse around values’ so that we might uncover where value is created, and also what those values might be, as we try to find ways of working with the digitally flexible and transformative characteristics of the emerging of participatory culture.

Hammersley somewhat ghoulishly, suggests that we first need the older generation in power to die off if fresh thinking capable of coping with a networked society is to gain traction in government in 2011. What Proboscis show us, less dramatically, is that with some applied heutagogy, thinking practically about how we might learn from ‘moving criteria across contexts’ at the start of a problem-solving process concerning public-sector innovation, along with some consideration of how we might create a ‘platform’ that could generate further innovative ‘state changes’, constrained by considerations of the nature of the public realm, then we can indeed enable public sector thinking that is in tune with the evolving networked society we live in at the start of the 21st Century.

Fred Garnett, April 2011

Final Reflections – Mandy Tang

March 11, 2011 by mandytang · Comments Off on Final Reflections – Mandy Tang

Creative Assistant

(6 Month Placement, Future Jobs Fund July 2010-January 2011)

It’s time to reflect on the past 6 months as the Future Jobs Fund placement has now come to an end, it really went by quickly! Other than the placement being too short, I can only think of the benefits I have gained with Proboscis during my time here.

It has been a great experience to explore more about the creative arts, with plenty of opportunities to utilise my artistic skills in all of the different stages of a creative process and exercising my knowledge with people of different backgrounds and experiences of their own.

I am also really grateful to Giles and Alice for their patience and teaching me many things ranging from local area knowledge to introducing artistic influences and techniques in hope that it would inspire me throughout the creative process of each project. With their kindness and constant guidance, they’ve become more of a mentor to me than simply my employers.

I also thank the New Deal of the Mind, firstly for organising this opportunity and providing scheduled sessions – The Goals Training programme, offering support and providing information about job hunting.

During the past 6 months I have been involved in various projects which include the storyboard eBook for Tangled Threads, then moving onto a project inspired by the Love Outdoor Play campaign with a full play set now known as Outside The Box. Once in a while I have assisted in the City As Material project and my more recent work is creating visual interpretations for Public Goods and designing eBooks to accompany the play sets for Outside The Box.

Outside The Box was a huge learning curve for me, I learnt many valuable lessons during the creative process. Firstly, how to manage my work flow better. The project became so much larger than anticipated that I found myself struggling with managing the workload, as I had tried to do too many things at once. Then there were elements on the actual product that I had learnt more about, such as decision making for a colour palette and how simplicity can convey ideas just as well as detailed illustrations. I believe there will be much more to learn from Outside The Box, as it will be going through the testing stage soon. I am excited and nervous to see what happens and I just hope that children will like and enjoy playing with them.

The biggest achievement whilst working on these projects was adapting. I was able to transfer many of my skills to fit each creative process but it was learning to think from a different perspective and presenting them in a innovative way which was the main challenge. The work flow and thought process also differed from my original training as a concept artist for games, as much of the work would follow a design brief closely, but with Proboscis it was very open and it possessed very little constraints making the possibilities endless.

I believe with all these achievements and lessons learnt, it will influence my work in future projects – the way I may approach ideas, deciding the colour palette, considering other ways to communicate my ideas across to reach a wider audience and to create art work that many can enjoy and appreciate.

This isn’t farewell! As I am very grateful for the opportunity to stay as part of the Proboscis team so I look forward to future projects and learning more about the creative arts, I’ll be posting about my work so make sure to visit!

Radhika Patel – Second Impressions

March 8, 2011 by radhikapatel · Comments Off on Radhika Patel – Second Impressions

Radhika here, the not so new Marketing and Business Development Assistant. It’s already been 4 months and here I am writing my second impression post… how time flies!

I last left off in the middle of the creation of the StoryCubes website, which has now been launched :). Having worked on the website and written numerous blog posts for promoting the StoryCubes, I have finally overcome my initial difficulty of blogging. This had led me to become a weekly ‘pop-up’ on the Bookleteer blog too, coming up with new and inspiring uses for Bookleteer. The part I enjoy the most, is actually bringing my ideas to life, by creating a mock up of each idea. It’s great seeing my ideas on paper instead of an image in my mind, and for all to see!

Even though I’m the Marketing Assistant here at Proboscis, my favourite part so far has been the opportunity I have had to dabble in all the projects that are happening, from City as Material to Mandy’s Outside the Box project (great fun!). Being able to be apart of a variety of projects has given me much more understanding about Proboscis, how they work and much more of an insight than I could have imagined.

Another bonus I have had working at Proboscis is putting my photography ‘skills’ into action! This has definitely been one of the highlights so far as I love being behind the camera and being taught by Alice or Giles on using the SLR and about lighting, is much more valuable than attending any class! I am very grateful I have had the opportunity to do this, as it’s something I enjoy and want to continue doing. 🙂

The placement so far has given me a number of opportunities to learn new things, especially finally learning how to use Photoshop, with the help from my fellow placements.

I have continued to learn from both Alice and Giles about the arts and can expect an inspiring story to pop up any time of the day. I feel this has been one of my most valuable experiences here, as before I wasn’t exposed to the arts industry and have been opened up to a whole new world if you like.

However, I am still trying to conquer the four flights of stairs every morning, but apart from the breathless moment I have once I get into the studio, I am enjoying every minute of my time here.

Visual Interpretations 1

January 21, 2011 by mandytang · Comments Off on Visual Interpretations 1

Hi all!

Whilst taking a break from Outside The Box I’ve been asked to create visual interpretations for a new project! I’ll be keeping a photo diary of my progress and will post up a photo each week for you all to see.

Alice suggested sticking up some of the visuals for the team to see and there will be plenty more to come!

Second Impressions – Mandy Tang

December 15, 2010 by mandytang · Comments Off on Second Impressions – Mandy Tang

Wow, it’s already time for me to write about my second impressions huh? If you’re wondering, it’s Mandy here! I started in July as a Creative Assistant for Proboscis, it’s been five months already!! Where did all the time go?! (laughs)

It’s been pretty busy during these five months, Giles and Alice have been cracking the whip to keep me busy working (T_T). Just kidding haha. They’ve been great fun, and most generous when offering advice and enlightening me with their knowledge, it always leaves me in awe with the amount of things they know.

Also, there has been more placements on board! Christina and Radhika are such lovely people, they both have a great sense of humour, easy to talk to and are always offering to help when it seems like I have too much going on (laughs). Oh and Moin; our programmer, joined just recently too! As for Haz… he’s been picking on me since day one!! that aside, he offers me assistance and I’ve enjoyed his blog posts and look forward to his future posts. Thanks guys for your help and support!

During the past few months I have been working on various projects. The first being Tangled Threads, then my current project Outside The Box and offering assistance here and there with City As Material.

Throughout these projects I sincerely thank Giles and Alice for trusting me with creating work without any pressure and just allowing me to carry out the projects to the best of my ability whilst offering kind encouragements. I tend to get carried away with trying to perfect everything so I thank you both for your patience and apologise for the delays!

If you remember reading my first impressions, I mentioned the many different assets in the studio either tucked away or on display and wondering about the story behind them… well… I’ve joined in with my own clutter! I’ve made so many Story Cubes I can build a fortress! Soon I’ll have enough to make a draw bridge to go with it (laughs).

It’s been really fun so far and I’ve learnt a great deal from Giles and Alice. I’ll do my best to fulfil my role and create work which others will enjoy! Have a great Christmas everyone!

Republic of Learning Redux

March 23, 2023 by Giles Lane · Comments Off on Republic of Learning Redux

Rachel Jacobs and I have recently written up a paper that explores the activities and achievements of our Republic of Learning workshops (2019-22). This post archives the previous posts about the workshops on our Manifest Data Lab website:

Republic of Learning 9: Creating a Reciprocal System

Updated: Mar 4, 2022

Our next Republic of Learning event will be on Wednesday February 2nd at 6pm London time. We will be hosting it online – using zoom.us. Facilitators: Dr Rachel Jacobs (artist, researcher) and Giles Lane (artist, researcher).

A workshop combining craft making, scientific data, intimacy, observation and stories to bring people together to imagine a human-made reciprocal and sustainable system that connects us back to the Earth’s own dynamic system (hydrosphere, geosphere, atmosphere, biosphere).

All Welcome, please book a free place via Eventbrite

Theme : Creating A Reciprocal System

AI, robots, driverless cars – machines that enable us to have “frictionless” lives and “satisfy” our every needs and dreams… What would a system look like that relies on reciprocity, sharing and gifting rather than ease, desire and consumption?

What is a reciprocal system?

This workshop will combine artistic and craft-based making to explore what a system of resilience, co-operation, re-enchantment and intimacy might be. It will bring together learning from previous sessions and work with the Earth’s planetary system (Atmosphere, Geosphere, Hydrosphere and Biosphere) to create a model for this new reciprocal system.

Materials that will help you make your reciprocal system:

- paper and/or card, pens, pencils, scissors

- any other craft or art materials you might have to hand (fabrics, string, newspaper, plasticine, paints etc…)

The workshop is free and will take place online on Zoom.

Documentation

We have created a booklet documenting the workshop, which can be viewed online or downloaded, printed out and made up into a paper booklet.

Republic of Learning 8: Little Earths, Mythical Objects & Human Stories

Updated: Mar 4, 2022

Our next Republic of Learning event will be on Wednesday December 8th at 6pm London time. We will be hosting it online – using zoom.us. Facilitators: Dr Rachel Jacobs (artist, researcher) and Giles Lane (artist, researcher) in collaboration with Dr Aideen Foley (lecturer & researcher, Birkbeck University of London).

What do we love, care for and want to protect? How would we feel about the planet – the places and non-humans that we love – if we could hold them in our pocket?

In this workshop we will make our own Little Earths, stewardship objects that combine craft making, intimacy, scientific data and stories. A mythical object to keep in our pocket, have in our home or gift to others.

All Welcome, please book a free place via Eventbrite

Theme : Little Earths, Mythical Objects & Human Stories

The Little Earths we make are based on the Russian nesting Babushka/Matryosjka dolls, worry beads and measurement cups. The Babushka doll is a folk object, nesting different sized dolls within each other to represent different layers of our selves. Worry beads act as a focus of prayer, meditation and mantras. Measurement cups are the most basic way we can measure materials to cook. Nested objects, whether inside each other or alongside each other, help us to see ourselves in relation to the world at different scales.

We will ask 8 questions. The first 4 questions will aid us to create the frame or structure of the Little Earth. These will respond to scientific data and observations at a global, national, local and then individual scale. The next 4 questions will help us explore how we might love, care and protect our Little Earth, responding to myth and folk tales. Leading us to each create a talisman for a more reciprocal future. Drawing on indigenous, folk, historic and scientific knowledge of climate, social and environmental change.

Through the act of making these objects we explore what we can gain from qualitative data (experience) as well as quantitative data (numbers) and how this can then be translated into acts of love, care and protection. Not seeking easy explanations (or judgements) but finding ways to pay attention, be present and share what our own senses and understanding of place, responsibility and change can bring.

For more about the concepts of Little Earths see: https://www.manifest-data.org/post/little-earths-stewardship-intimacy-and-community

Materials that will help you make your Little Earth:

- paper and/or card, pens, pencils, scissors

- 4 nested jars, pots, matchboxes, cardboard boxes or measurement cups or 4 different sized envelopes

- any other craft or art materials you might have to hand (fabrics, string, newspaper, plasticine, paints etc…)

The workshop is free and will take place online on Zoom.

Documentation

We have created a booklet documenting the workshop, which can be viewed online or downloaded, printed out and made up into a paper booklet.

Republic of Learning 7: Atmospheric Commons

Updated: Mar 4, 2022

“In the space between the past and future, having and losing, knowing and not knowing, lies an opportunity for awakening” (Prideaux 2021)

Our next Republic of Learning event will be on Thursday June 24th at 3pm London time. We will be hosting it online – using zoom.us. It will explore our past and present impacts on the Earth’s atmosphere – personally, locally and globally. We then seek to imagine whatever comes next… making artistic/craft based responses that combine scientific data with our own questions and stories about the future.

All Welcome, please book a free place via Eventbrite

Theme : Atmospheric Commons

We consider the atmosphere as a nebulous commons, transformed by extractivist acts of enclosure that dissipates and reforms as a material record of our politics, behaviours and histories. This collision of the sensory and the political occurs across huge scales, connecting geo-chemical processes; fossil necro-deposits; carbon industries; petroleum-states; infrastructures; service companies; governance; and energy and futures markets.

Using speculative mappings; animations, physical models and public workshops we chart the processes of planetary energy exchange that compose the atmosphere alongside the socio-technical assemblages refiguring it.

We seek to examine our personal connections to energy, distribution and consumption and develop figures, expressions and situations that ask, “Who owns the air?”

From “Political Atmospherics” by T Corby et al, in Freeport: Anatomy of a Black Box (Matadero, forthcoming 2021)

You are invited to do a simple activity before the workshop that maps your energy interactions and relationships to the complex carbon system we live within. These maps will inform what happens in the workshop as a starting off point for our dialogues and discussions. Download a PDF of instructions here:

MDL_Energy_Map.pdfDownload PDF • 7.04MB

Materials to have at hand:

For the workshop itself, we also suggest that some of the following materials would be helpful to have in place for the workshop, if you can get hold of them:

- 2-3 metal coat hangers

- Scrap textile material (e.g. old clothes, pillow cases)

- Old magazines, newspapers, birthday cards

- Cardboard, products/cereal boxes

- Blue tack, plasticine, glue, tape

- String or wool

- Other found objects (stones, shells, flowers, leaves, strange plastic things, rubbish etc…)

- A pen or sharp pencil

- Scissors

Please get in contact as soon as possible if any of this is going to be an issue and we will try and help out, or if you have any other questions about the activities or accessibility.

Documentation

We have created a booklet documenting the workshop, which can be viewed online or downloaded, printed out and made up into a paper booklet.

Republic of Learning 2021

Updated: Nov 25, 2021

After a long hiatus due to the pandemic, we are happy to announce a new series of online Republic of Learning workshop events, with the first on Thursday 24th June 3-6pm.

“In the space between the past and future, having and losing, knowing and not knowing, lies an opportunity for awakening” (Prideaux 2021)