The New Observatory: installation images

June 29, 2017 by Giles Lane

- Lifestreams installation shot : The New Observatory. FACT, Liverpool (2017). Image: Gareth Jones.

- The New Observatory. FACT, Liverpool (2017). Image: Gareth Jones.

- The New Observatory. FACT, Liverpool (2017). Image: Gareth Jones.

Lifestreams at the New Observatory

May 15, 2017 by Giles Lane

A selection of the data objects created for our 2012 project, Lifestreams, (and our film) will be exhibited as part of The New Observatory show at FACT from 22nd June to 1st October. Curated by Hannah Redler and Sam Skinner, the show “brings together an international group of artists whose work explores new and alternative modes of measuring, predicting, and sensing the world today through data, imagination and other observational methods.”

Augmented Reality Advent Calendar

March 17, 2017 by aliceangus

As part of my ongoing work with the Mixed Reality Lab and Horizon DER at Nottingham University I was commissioned to come up with an augmented reality, paper based, activity pack or object that incorporated their Artcodes pattern recognition system. MRL wanted to create something to help them with their ongoing research into the social aspects of pattern recognition technology. Ive been working with Artcodes on and off for a couple of years and am interested in seeing it develop more so that it can be used more widely by people to share and author their own digital content. I’d like to use it in some of my public art projects and work with groups and organisations so I was keen to use this commission to research more about how and why people might use this kind of system, what works and does not and where or how it can be socially useful.

I researched and mocking up various festive ideas for traditional decorations, cards and advent calendars, we tried these out and decided to go with the advent calendar, Advent Calendars are very familiar and fit with the idea of the codes opening digital doors. A nice calendar is a treasured item that many people use year after year and this fitted with my thoughts about it being something people would want to have out and play with, and could share and use again.

I designed and illustrated it as a freestanding, gatefold calendar with 24 opening doors. It is traditional in style and features scannable Artcodes to use with the Christmas with Artcodes app. The calendar comes with 24 Artcode stickers to put under any doors . When scanned, using the Christmas with Artcodes app, these codes open photos, videos and other media. People could personalise and replace all the content by adding their own (photos of text, images, drawings, sound, video, urls etc) and share their digital layers with other calendar owners who could view the digital layer created for them. Everyone with a phone or tablet can use the same calendar and create their own digital layer.

I’ve been surprised by the range of uses people found and in particular the empahsis on using it to make a connection with people isolated or far away. Those uses included making a calendar for a friend having a long term hospital stay; making calendars of family memories, and having your own calendar whilst sending one overseas to share christmas messages between family far away.

A lot of what the team are discovering is about the language and processes that make sense to one person but are confusing to another. When you take a risk and invite people to try out a new technology the uses people find for defy your imaginaton, they find unusual ways to use things and uses for things. If people are not creatively involved in development of technologies it can limit the potential for those technologies to develop in useful social ways.

Attentive Geographies

March 13, 2017 by aliceangus

Since we worked together on Storyweir in 2012 I have had an ongoing relationship Exeter University’s GEOCAK (the Geographies of Creativity and Knowledge) research group, most recently working on the Attentive Geographies project which began in 2014/15. I have been commissioned to create new artwork reflecting on the work of the group, following from running a two day workshop and participating in a series of events over the last 2 years with the group.

Attentive Geographies looks at creative practice as research process. GEOCAK are working with artists and writers to better understand; “What happens when you commit to deepening and developing skill? What emerges when methodology becomes the subject of research? How does collaboration emerge through creative methodologies? What does it mean to be a geographer as practitioner?”

There is a strong and deepening relationship between geography and creative practice – art, music, writing and those practices are increasingly shaping Geographers processes. The project will identify new ways geographers can extend their skills through a variety of creative methods, skills and approaches.

Initially I produced a series of drawings based on my interactions and discussions with the group, this is developing into another series of illustrations, contributions to the forthcoming book “Attentive Geographies”, and new textile work in response to the research practices of the group.

“The creative turn in Geography has cemented the long-standing relationships between geography and creative practitioners. Creative geographies are no longer studied as a product, instead practices are attentively shaping their learning, doing and knowing, with geographers working and developing their capacities with a variety of creative methods, skills and approaches.

‘Attentive geographies’ explores creative practice as research process. What happens when you commit to deepening and developing skill? What emerges when the subject of research, becomes methodology? What is gained by undertaking creative geographies by doing? What difference does the practical doing make? How does collaboration emerge through creative methodologies? What does it mean to be a geographer as practitioner?”

Geographies of Knowledge and Creativity Research Group 2015

Data Manifestation Talk at Open Data Institute

December 21, 2016 by Giles Lane

Back in June I gave a talk on data manifestation and our Lifestreams project at the Open Data Institute :

Read Giles’ post, How Do We Know? for more details on the project.

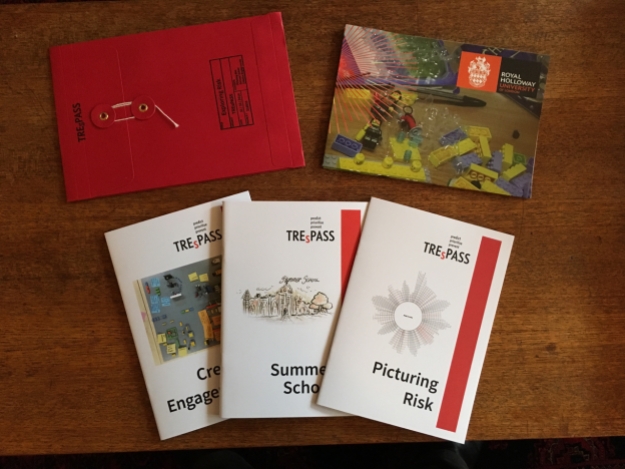

TREsPASS Exploring Risk

December 2, 2016 by Giles Lane

This Autumn Giles has been working with Professor Lizzie Coles-Kemp and her team in the Information Security Group at Royal Holloway University of London to produce a publication as a deliverable for their part of the TREsPASS project.

TREsPASS : Technology-supported Risk Estimation by Predictive Assessment of Socio-technical Security was a 4 year European Commission funded project spanning many countries and partners. Lizzie’s team were engaged in developing a “creative security engagement” process, using paper prototyping and tools such as Lego to articulate a user-centred approach to understanding risk scenarios from multiple perspectives. The three books and the poster which comprise TREsPASS: Exploring Risk, describe this process in context with the visualisation techniques developed by other partners, as well as a visual record of the presentations given by colleagues and partners at a Summer School held at Royal Holloway during summer 2016.

The publication has been produced in an edition of 400, but all 3 books included in the package are also available to read online via bookleteer, or to download, print out and hand-make:

Exploring Risk collection on bookleteer:

We are now starting a follow on project to develop a creative security engagement toolkit – with case studies, practical activities and templates – which will be released in early 2017.

TKRN in Vanuatu Again

September 5, 2016 by Giles Lane

Just over a week ago the Tupunis Slow Food Festival on Tanna island, Vanuatu concluded. It was the first festival of its kind held in Melanesia – bringing together people from Vanuatu, Papua New Guinea, Bougainville, New Caledonia (Kanaky); the Solomon islands and Fiji to celebrate traditional ways of producing and preparing food as part of a redefinition of “development”; rejecting the simple monetary definitions (dollars per day) and exploitative, extractive industries that characterise what global institutions such as the World Bank and the IMF define as development in favour of alternative criteria that recognise the value of sustainable land and sea tenure, the qualities of organic grown food and traditional methods of preparation, and the richness of lives not governed by the need for money. The festival was organised by a coalition of local organisations (including Vanuatu Slow Food Network, Vanuatu Land Defence Desk, Vanuatu Cultural Centre, Tafea Cultural Centre) and supported by The Christensen Fund as well as the Vanuatu Government.

As part of our TK Reite Notebooks project, James Leach and I travelled to participate in the festival along with three people from Reite village in Papua New Guinea – Porer Nombo, Pinbin Sisau and Urufaf Anip – with whom we have been co-designing the TKRN toolkit since 2012. Our trip was intended to bring the TKRN project and toolkit to a wider audience of Melanesians interested in documenting and preserving traditional culture – with the focus on presentation being led by Reite people themselves (rather than James and myself). Our role was to facilitate and support, with the key exchange of ideas, tools and processes taking place between people indigenous to Melanesia themselves.

This is a key aspect of the project for us – having our co-design collaborators from Reite village be identified and engaged with as cultural leaders in their own right who are actively taking steps to document and transmit their living culture and knowledge traditions to future generations in the face of extreme pressure from “development”. For most of our time we were also accompanied by Yat Paol, a PNG man of the Gildipasi community with whom we worked in Tokain village earlier this year (and a representative of The Christensen Fund in PNG). Yat’s insight and gentle wisdom concerning the importance of self-documentation of traditional knowledge as a means for indigenous people to empower themselves has been a source of inspiration and a great sounding board for us.

Porer and Pinbin represented Reite on a panel bringing perspectives from various Melanesian communities and spoke about the project and the importance of kastom, land and bush. For many people at the festival the emphasis was on a return to traditional ways of life – having two people who come from a community that maintains its traditional way of life speak about what it means to them and their families truly caught the mood of the audience and their response was fantastic, giving rousing applause.

The festival ran over 5 days and had speakers from across the region, as well as performances by cultural groups, traditional crafts, music and demonstrations of new ideas for food preservation and health initiatives. Moreover, each day traditional foods were prepared and cooked by people from all the provinces and islands of Vanuatu (and New Caledonia) for attendees to sample. Thus we were feasted on a daily basis on everything from (and often in locally specific combinations of) taro, yam, manioc, tapioca, cassava, banana to fish, coconut crab, goat and beef.

The Vanuatu Daily Post’s Life & Style section has an article on the festival here, and Sista.com has an article with excellent photos from the festival here.

At the festival we connected with Canadian anthropologist, Jean Mitchell, who is running a project (Tanna Ecologies Gardens & Youth Project) with young people on Tanna documenting and recording kastom gardens and traditional foods. James, Urufaf and I ran a TKRN workshop with a group of them, teaching them to fold and make notebooks, as well as co-designing a new custom notebook for their project. A couple of days later we demonstrated scanning in the first few completed books and printed out copies for the young people who had made them. Our simple bush publishing set up of laptop, scanner and printer meant that we were able to do this quickly and simply – working in basic conditions on site and being able to carry all the equipment we needed in a couple of backpacks. Jean’s project is an extension of one she originally developed in 1997, the Vanuatu Young People’s Project, with the Vanuatu Cultural Centre. Over the next two years the young people on Tanna will be documenting as much knowledge about traditional kastom gardens as they can, using the TKRN toolkit as their primary tool. Jean has worked with them this summer to develop a questionnaire template which has been adapted for the notebooks:

Once back in Port Vila, Jean also arranged for us to train a couple of young people who will be sharing their skills with the men fieldworkers of the Vanuatu Cultural Centre at the annual fieldworkers’ meeting at the end of September. This will complement the work we did in March with the women fieldworkers and hopefully bring the TKRN toolkit to many different communities across Vanuatu.

At the festival we also met and had great conversations with Dr Ruth Spriggs and Theonila Roka-Matbob from Bougainville (a semi-autonomous part of PNG), who are setting up an Indigenous Research Centre on the island, and Professor John Waiko of Oro Province PNG and his son, filmmaker and slow food activist Bao Waiko, from Markham Valley PNG (where he lives with his wife, Jennifer Baing-Waiko, also co-director of Save PNG). We’re hoping to share the TKRN toolkit with their initiatives as part of our next steps.

L to R: Professor John Waiko; Dr Ruth Spriggs, Theonila Roka-Matbob; Betty Gigisi; James Leach & Bao Waiko

A highlight of our trip was a visit to Tanna’s famous Mount Yasur volcano, truly awe inspiring:

Before attending the Tupunis festival, we took the opportunity to build on a relationship we had initiated with Wan Smolbag Theatre during our previous trip to Vanuatu earlier this year. Through co-founder Jo Dorras we were introduced to researcher Ben Kaurua and digital trainer Cobi Smith with whom we ran a TKRN workshop introducing the books and documentation process to a group of young volunteers who work with various island communities living in and around Port Vila, the capital on Efate island. (I had designed a very simple custom notebook for WSB in advance of travelling). We were also introduced to some local Chiefs from the nearby Lali community and were invited to attend a ceremony that was part of a boys’ initiation ritual. We left WSB with some new equipment to assist them in using the TKRN toolkit (a Polaroid Snap camera/printer & Zink sheet packs, as well as a low cost Canon combined inkjet scanner and printer) and are hoping to see some results in the future.

Porer speaking at IUCN

After the festival, while I returned to the UK and Pinbin and Uru returned to Madang, James and Porer continued on their travels to participate in the IUCN World Conservation Congress in Hawaii. There they took part in a session on indigenous documentation to demonstrate the TKRN process and toolkit, and to discuss the complex issues facing traditional communities who wish to preserve their culture and values and to transmit them to future generations.

This trip was the final activity of our recent TKRN programme – we are now preparing a new programme of activities that aim to build a lasting legacy for the project and enable the establishment of a network of indigenous groups and local organisations in Melanesia to adopt and adapt the TKRN toolkit for themselves. Huge thanks are owed to Catherine Sparks of The Christensen Fund who made so much of this possible; funding many of the projects, organisations and the festival itself, as well as being the consummate connector introducing people and taking care so that everyone had the most productive time possible. Thanks also go out to Paula Aruhuri, Joel Simo and Jacob Kapere who were instrumental in inviting us, arranging travel and accommodation and making time and space for us on the programme.

More TKRN work in Papua New Guinea

May 27, 2016 by Giles Lane

I’ve recently returned from Papua New Guinea where, with James Leach, I have been doing field work for our TK Reite Notebooks (TKRN) project. This follows on from our work last year in Reite village on Madang’s Rai Coast, and also from our trip to Vanuatu in February, where we worked with a group of women fieldworkers and the Vanuatu Cultural Centre.

Having established the model of working with the notebooks with Reite villagers last year, the focus of our trip in this second year of the project was not to produce more books, but to explore how and if the model would work with other communities and, to find other local partners for whom the tools and techniques we have developed could be useful additions to their own methods and practices of documenting traditional knowledge.

Through our close discussions with Catherine Sparks and Yat Paol of The Christensen Fund (our project’s main sponsor), we identified some possibilities – the Research + Conservation Foundation (RCF) of Papua New Guinea (in Goroka, Eastern Highland Province); and Tokain village, Bogia District (Madang Province). Having arrived in Madang and met up with two of our key collaborators from Reite – Porer Nombo and Pinbin Sisau – we made plans to travel up the coast to the village of Tokain and stay a few days to introduce our model to local people. James and I then travelled to Goroka to spend a day at RCF meeting with their director, Sangion Tiu, education programme manager, Emmie Betabete, and resource officer, Milan Korarome. We learnt about RCF’s work in communities and in teacher training, and presented our TKRN approach. This resonated strongly with RCF whose staff spoke of the problem of documenting traditional knowledge in both school and village settings. It was a lovely moment when their enthusiasm for the books spilled over and we decided on the spot to co-design a new template with them. We then spent a while devising questions about climate change for elementary schoolchildren, which RCF will pilot this summer.

We returned to Madang after this highly successful meeting and the next day set out for Tokain with Porer, Pinbin and another young man from Reite, Urufaf, who has become a key proponent of using the TKRN books in his own community. Piling aboard a PMV (an open back truck with benches and a tarpaulin for sun/rain cover) we bumped along the highway following the coast north for about 4 hours before arriving. Many people from the village turned out to meet us and hear Porer, Pinbin and James introduce what the Reite villagers had done with the TKRN books and why it was important to them to preserve and transmit their culture and knowledge to future generations this way. The following morning we walked around different parts of the village meeting people going to market and in the community office, where they have a laptop and printer/scanner of their own, giving us an opportunity to demonstrate the whole cycle of printing off a PDF booklet, filling it in, scanning and storing it as a PDF on the computer and printing out another copy of the scanned book.

Then we addressed all the students from the elementary and primary schools, their teachers and some of the village elders – again, the focus being on the Reite villagers explaining their use of the books and how the school in Reite had adopted the books as part of their own curriculum activities on environmental science and cultural heritage. This indigenous or local exchange of documentation practices (with James and myself taking a secondary role as facilitators rather than teachers) is very much the beginning of where we see the TKRN model developing in the future. The afternoon was spent workshopping ideas for the booklets and getting people used to the cutting and folding process for making up the books, as well as taking their photos to stick onto their books – always a popular aspect of the process. This continued well into the night with the convivial atmosphere of a house party surrounding the guesthouse where we stayed.

We left Tokain having agreed to meet up in a week or so’s time with a representative from the village who would bring us the first batch of completed books to scan and for me to build a simple website for – as I did last year for Reite (Reite Online Library).

From Madang we set off across Astrolabe Bay and down the Rai Coast to return to Reite for a few days and discuss with the community what had happened since our last field trip and what we proposed to do next. A meeting was organised and many people also came from neighbouring villages and hamlets: Sarangama, Asang, Marpungae and Serieng. Porer, Pinbin and Urufaf all spoke about the project, what was achieved last year, what we had just done at Tokain and how important it is for knowledge to continue to thrive and be passed on to future generations despite all the changes happening to the world around them. James also spoke of our visit to Vanuatu, how we had shared some of the Reite books with the indigenous fieldworkers there and we showed them some of the books made by the ni-Vanuatu people we met.

The response was dramatically positive, with people calling for a revival of teaching and learning in their traditional local language, Nekgini, alongside using Tok Pisin to document stories and practices. A core group of people interested in taking the lead to build up a library of traditional knowledge also emerged, a group who were also prepared to go ‘on patrol’ to other local villages to share with them the TKRN methods. We left over 250 blank books in the village, as well as a simple to operate Polaroid Snap camera (and several hundred sheets of Zink photo paper) to take and print out photos of people to stick on the front covers. By shifting the focus from the familiar and everyday towards the more esoteric, and perhaps endangered, types of knowledge of their environment that Reite people have, we are hoping they will be able to develop a truly unique and exemplary library that could inspire others across PNG, Melanesia and perhaps even farther afield to document their traditional knowledge before it is lost. We also took the opportunity to improve the design of the books, redesigning the front covers to allow for more contextual information about the author and the books contents, and rewriting the engaged consent statement on the front for better clarity.

Returning again to Madang we met with Ernest Kaket from Tokain and scanned in the books he’d brought with him from the village. These now form the foundation of their own online library which we hope to expand in due course.

Our next steps are to make a return visit to Vanuatu with a couple of Reite villagers to introduce their use of the TKRN model themselves; and to continue to develop the basis of a partnership with RCF as a means of extending the reach across PNG of the tools and methods we’ve co-created with Reite people.

Lifestreams Redux

March 24, 2016 by Giles Lane

This week I presented a new generation of lifecharm data shells at a symposium on ethics in data science for the Alan Turing Institute. The shells were created by Stefan Kueppers using the Lifestreams process for data manifestation, and used data from a research project led by Professor George Roussos at Birkbeck University of London which records symptoms of Parkinson’s Disease as experienced by sufferers.

These shells are an initial experiment flowing just 3 data sources into the shell growth parameters, which we hope to expand with further data sources and increase the complexity of the model in future generations. The aim is to capture the high variation in symptoms experienced by those with Parkinson’s as an alternative to the way in which patients’ complex symptoms are collapsed into the single summary statistic of the Universal Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale.

Read my provocation piece for the ATI symposium for more information.

Artcodes and smart textiles at the Mixed Reality Lab

March 16, 2016 by aliceangus

Since 2015 I’ve been working with the Mixed Reality Lab and Horizon Digital Economy Research at Nottingham University on their Artcodes/Aesthetocides . I have been part of the Artcodes research team and my work involves helping to research and develop the system through trialing and using it in public situations and testing out artcodes as part of public artworks, in social situatuions, working with groups and members of the public and experimenting with with textiles.

In my textiles reaearch I have been looking at how fabrics and drawings might ‘come alive’ in different ways with the stories that inspired them. My interest is in how the codes can be used materially with fabric, and socially, how they might work in different public situations, in the heritage sector and on costumes in theatre/performance.

The Artcodes app recognises visual codes (artcodes) within sophisticated patterns and illustrations. It allows you to create codes that can be made part of patterns and designs on everyday objects and in artworks. In contrast to image recognition the Artcodes system does not ‘recognise’ a specific image but it scans for a number of solid and blank spaces which can be in any configuration. This means that the shape can change but the code will still be recognised, the code can be shared between different images or patterns, or there can be multiple different drawings that contain the different codes.

I am looking at how codes and be used with different fabrics; as part of artworks, workshops and projects and in garments as part of performances with codes embedded into garments and costumes.

Bookleteering with the Vanuatu Cultural Centre

March 14, 2016 by Giles Lane

Over the past 2 weeks I have been in Port Vila, Vanuatu in the South Pacific with James Leach and Lissant Bolton (Keeper of Africa, Oceania and the Americas, British Museum) working with the Vanuatu Kaljoral Senta (Bislama for Vanuatu Cultural Centre). Lissant organised and led a special workshop with a group of women fieldworkers on the theme of current changes to kinship systems (supported by the Christensen Fund). The fieldworkers are ni-Vanuatu (local) people representing some of the many different vernacular language groups from across the many islands who do voluntary work to record and preserve traditional culture and knowledge. The fieldworker programme has been established and overseen by the Cultural Centre (VKS) for over 35 years and is a unique initiative where local people gather “cultural knowledges about all the aspects of the customary art of living of Vanuatu”. Each year the fieldworkers gather together to share their research with each other and contribute to the documentation held at the VKS.

Lissant had invited James and I to visit Vanuatu with her and introduce the TKRN toolkit and techniques to the fieldworkers participating in the kinship workshop, as well as to meet with others working on different projects at the VKS. The low cost and ease of use of the TKRN booklets – both for collecting documentation in rural settings as well as digitising and archiving (both online and as hard copies) – made it an obvious tool to share. Prior to leaving London, Lissant and I had made some initial examples of Bislama (the local pidgin) notebooks for Vanuatu similar to those created in Tok Pisin for Papua New Guinea. These would be tested with the women fieldworkers during the workshop and we planned to adapt them with their assistance, as we have done in PNG with local people from Reite village.

In Port Vila James and I were also were introduced to Paula Aruhuri of the Vanuatu Indigenous Land Defence Desk, an organisation that promotes awareness of indigenous custom and land rights across Vanuatu and campaigns to stop land alienation from traditional owners. With Paula we co-designed a simple reporting notebook for the fieldworkers who deliver awareness events to local communities that will assist the land desk in documenting local people’s concerns and how they might be able to help them. And we met with Edson Willie of the VKS Akioloji Unit (Heritage Unit), with whom we co-designed a notebook for fieldworkers to record heritage sites.

The women fieldworkers experimented with one of the notebook formats and helped us re-design the front cover and write up a more appropriate ethics statement that reflected their different concerns about sharing traditional knowledge. In this case they chose not to share their books online (as we did in Reite), but to have them scanned, re-printed and stored in the ‘Tabu Rum’ of the VKS, the audio-visual archives. Local concerns about rights to aspects of traditional knowledge in Melanesia are a major theme and extremely important to design for. Developing tactics and a strategy to enable clear documentation and permission for sharing has been at the heart of the TKRN co-design process. Lissant has written about this issue in the context of Vanuatu and it also reflects on James’ work with Porer Nombo from Reite on their book Reite Plants in this essay.

We are planning to return to Vanuatu later in the year with some Reite people to participate in a knowledge exchange around the TKRN toolkit and techniques with men and women fieldworkers of the VKS. In this way we hope to develop a model of adoption whereby communities learn from each other how to use and adapt the toolkit for their own purposes, with our role being more one of facilitation than education or training. As a toolkit designed from the grassroots up, I hope to continue expanding on the concept of ‘public authoring’ that has driven the development of bookleteer and the ‘shareables’ it enables people to make and share.

In late April James and I will return to Papua New Guinea to work with Reite villagers to introduce the TKRN toolkit to a couple of other villages in Madang Province – this should provide an good indication of the possibilities and limitations of how a model of community knowledge transfer and adaptation can work.

Reite Village Online Library

September 21, 2015 by Giles Lane

This website has been created as an online library of TKRN notebooks made by the villagers of Reite and its neighbours in Papua New Guinea’s Madang Province. These books were created during a field trip in March 2015 and we hope to add many more in the future. We aim to transfer management of the site to the villagers themselves in due course, so that they can continue growing the library for future generations. As 4G mobile internet service penetrates into the jungle where they live and more local people own smartphones and connected devices, this is an increasingly likely possibility.

Mixing the physical and digital in this way means that traditional knowledge and customs may be preserved and transmitted forwards by embracing some of the changes that industrialisation and urbanisation bring to traditional rural communities. By working alongside the existing relationships of knowledge exchange it offers new opportunities for inter-generational collaboration on self-documentation of stories, experiences, history and practical knowledge of working with and sustaining the local ecology and environment.

The site itself is extremely simple and uses only free services: a free WordPress.com blog as the primary interface for organising and sharing the books; and a free Dropbox account as the primary repository of the PDF files of the scanned books. It is a key component in our TKRN Toolkit, and closes the loop in our use of hybrid digital and physical tools and techniques.

The villagers themselves developed their own categories and taxonomies for cataloguing the books, which have all been tagged accordingly. The books are thus searcheable by title, author and subject(s). Many of the books include an author photo on the cover page; a thumbnail image of the scanned book was included in each post, and a blog theme chosen that presents the main page as a mosaic of images from the posts. For communities with highly varied literacies, it also enables visual recognition both of the author’s faces, and in many cases their handwriting or drawing style.

TKRN Blank Notebooks

September 17, 2015 by Giles Lane

These notebooks have been co-designed with villagers of Reite in Madang Province, Papua New Guinea by Giles Lane and James Leach as part of the TK Reite Notebooks project and Toolkit. They can be downloaded, printed out and made up into physical notebooks for recording traditional knowledge. Then they can be scanned and shared online or as physical objects.

The books have been created using bookleteer – Proboscis’ free self-publishing platform. Each link is to an A4 PDF file. The “view options” links open each notebook’s page in bookleteer with US Letter PDF and a web readable version.

16 page Standard Notebook with Questions – Tok Pisin • view options

16 page Standard Notebook with Questions – English • view options

16 page Teaching & Learning Notebook with Questions – Tok Pisin • view options

20 page Multi-stage Processes Notebook with Questions – Tok Pisin • view options

16 page Story Notebook with Questions – Tok Pisin • view options

12 page Initiation Notebook with Questions – Tok Pisin • view options

16 page General Purpose Notebook (No Questions) – Tok Pisin • view options

16 page Structured Notebook with Question – Bilingual Tok Pisin/English • view options

View the TKRN Notebooks collection on bookleteer.

We also have created this guide to folding and making up the notebooks (in English/Tok Pisin) :

Making London Event

August 29, 2015 by Giles Lane

Back in July Giles delivered a workshop on “Peeking over the Horizon” for the University of Greenwich’s Making London event. Below is a short video of the day:

Making London – Design Workshop from Creative Conversations on Vimeo.

#MakingLondon was a workshop-based event which considered different approaches to how the creative and cultural industries can continue to innovate in an increasingly corporate and financial capital.

For more information on this and other Creative Conversations events go to http://blogs.gre.ac.uk/creativeconversations/

Reflecting on Urban Tapestries

July 6, 2015 by Giles Lane

Ten years ago we published Public Authoring, Place and Mobility – a report on the Urban Tapestries project (2002-04) which brought together all that we had learned, described our methodologies and activities, evaluated our achievements and presented a series of policy proposals. I have been re-reading it to see how well our ideas have held up over the past decade, and to what extent they have been borne out by the development of social media, the mass adoption of smartphones and connected devices, and by social and cultural behaviours.

Urban Tapestries was conceived in June 2002, just after we had completed another project, Private Reveries, Public Spaces (2001-02), which explored the social and cultural impact of the emerging mobile communications revolution. We started to imagine what the effects would be on how people inhabit urban space once the physical topography of the city could be overlaid with an invisible data landscape accessible via mobile devices. Such “location based services” were then only in their infancy (in places like Japan via DoCoMo’s i-mode service) and nearly all the academic and industry research projects of the time focused on their potential use as tourist guides.

Urban Tapestries set out to imagine and investigate the everyday – how might people use them in everyday life: on the way to work or school, going to the supermarket, visiting the doctor, socialising or playing in a park. Funded through an unusual public/private mix, the project set out to peer into the future ten years or so ahead. We sought to articulate a vision that was grounded in actual social situations and cultural behaviours, and not just to rely on imagined scenarios and invented personas.

The report contains a wealth of observations and insights gained from our iterative and participatory process. We combined paper prototyping with social engagement, user trials of functioning systems in public settings as well as numerous public workshops and events where we shared and discussed our ideas as the project progressed. Below are some of the policy proposals which we made back in 2005 along with some comments on how the ideas behind them fare in 2015.

We followed UT with a 5 year programme of projects called Social Tapestries (2004-09), where we sought even further to embed our research in actual communities and situations. Through a series of discrete projects we explored our concepts of public authoring and social knowledge in ways that prefigured many of today’s familiar tropes : wearable sensors and citizen science, civic engagement and participation, big urban data and environmental mapping, hybrid digital/physical interfaces, robotics and hacking, to name a few. In these we sought extend and deepen the insights, working with real communities in actual places to explore what opportunities could become realities.

- Innovation from the margins to the centre

Governments, researchers and businesses need to pay greater attention to the needs of actual people in real contexts and situations rather than relying on marketing scenarios and user profiles.

Co-design and co-creation techniques along with iterative and agile development processes have become commonplace, especially through the concept of minimum viable product as a means of fast and iterative development of new products and services. Although not ubiquitous, they are far more likely to be present in the development of services that engage people, from the grassroots to industry, commerce and government. If this trend continues it bodes well for the role of the actual people in the design, testing and implementation processes of services intended for them. - Open Networks for Mobile Data

Telecom network operators need to recognise the desires of people to communicate (by voice or data) with each other irrespective of the company they purchase their service from.

Its hard to think back to a time when mobile data was restricted to the network operators own “walled gardens”, but it was actually not so long ago. With recent changes to EU data roaming laws bringing down national barriers by 2018, a whole new wave of data mobility will be realised. ‘Net neutrality’ remains a contested standard though, as all kinds of network and service providers (not just mobile) increasingly converge their offers and seek to maximise revenues for high value content. - Open Geo Data

There is a clear and pressing need for free public access to GIS data to make public authoring and a host of other useful geo-specific services possible.

The growth of open mapping platforms like Openstreetmap as well as services like Google Maps and Google Earth made possible the rapid growth of user-created georeferenced projects and services in a short space of time. Yet the major owners of GIS data (such as Ordnance Survey) have only slowly and partially opened up their systems for free use by the public. The planned release of the UK’s entire LIDAR data in 2015 by Defra may be a signal moment in the shift from the proprietary model of mapping by the state towards a more democratic understanding of mapping a a civil process in its own right. - Reinvigoration of the Public Domain

Public authoring has the potential to be a powerful force in enriching the public domain through the sharing of information, knowledge and experiences by ordinary people about the places they live, work and play in.

Social media has exploded into the public realm and has arguably taken a significant role in facilitating entirely new ways for people to share what they know and experience, as well as to organise all manner of movements for action and change. People’s willingness to share with unknown others underlines the essential human quality that seeks to build new relationships, new communities wherever we go. In counterpoint, the Snowden revelations have given weight to concerns about the extent of state surveillance that circulated since the late 1990s (cf the Echelon network) and the degree to which free speech is inevitably curtailed by self-censorship when people are aware that their every utterance and communication may be intercepted at will, now or in the future. Nevertheless, our abilities to form new communities around ideas, campaigns, issues and passions have been continually advanced by the depth and speed that these forms of social media have enabled. - Public Services Engaging with People

Public authoring could be employed to create new relationships of trust and engagement between public services and the people they serve. Public authoring proposes a reciprocity of engagement whereby public services would not just provide information but benefit directly from information contributed by citizens.

Our ideal of new trusted, reciprocal engagement between citizens and public services has not quite emerged as we may have hoped, however there have been indications that such change is afoot, not least in the expanding area of open (public) data. That more public organisations are allowing others to access and use their data for their own purposes suggests hope for the future. There is much more that could be done to both increase transparency and to increase the role of citizens in the management of our communities. State surveillance is also a factor affecting people’s sense of agency and trust in governmental mechanisms that will have to be continually addressed as we shape the future of our democracies. - Market Opportunities

The wealth of public data created by public authoring will provide many market opportunities for business people and entrepreneurs. The not-for-profit sector needs to embrace the energy and creativity this engenders as much as the commercial sector needs to embrace the need for people to be more than just consumers.

The dividing lines between “public” and “private” have become ever more blurred in recent years. The impacts of austerities imposed since the 2008 banking collapse and subsequent ongoing economic turmoil have seen areas previously the preserve of the “public sector” outsourced to private enterprise under the guise of “efficiency” and profit. This was certainly not what we envisaged as it has imposed a narrow financial interpretation of value and excised almost all considerations other than the purely monetary from decision making. By transferring more and more of our public services in this way, the scope and legitimacy of democracy are undermined. We need to reaffirm other measures of value that have been pushed aside and stand firm for their re-adoption as standards to aim for so that we can indeed create diverse new opportunities in both “public” and “private” sectors. - Location Sensing & Positioning

The technological imperative for defining a person’s position needs to be dropped in favour of an approach that incorporates the rich nature of the physical world’s location information – street signs, shop signage etc.

Our insistence on not becoming entirely beholden to GPS, Glonass & Gallileo was perhaps a little brusque. However, there has also been a growing sense of discomfort with the purely digital. More and more people have become involved in making things: learning old manual skills that can be intertwined with newer digital ones. This hybrid digital/physical approach seems more and more plausible with each year. - Including Everyone

The drive to use the latest technologies and services must not exclude those who choose not to adopt them, or cannot, for whatever reason.

As with recent critiques of the Smart City concept, our emphasis in the report rested on active citizenship being at the heart of the potential opportunities being offered by these mobile, location enabled services. This necessitates including everyone in benefiting from the opportunities offered, not just restricting access to those able to afford to pay. There has been much debate over the intervening years about access to the internet having become effectively a utility needing the same statutory regulation as access to fixed-line telephones. If a government wants to engage its citizens on a “digital-first” basis, it must make sure that there is provision for others not able, for any reason, to access via other means – setting a standard that other services can emulate or aspire to. - Time and Relevance to Everyday Life

These new forms of communicating will not appear overnight but will need careful cultivation and time to flower. To realise their fullest potential they will need more than just grass roots enthusiasm and activism. They will require regulatory nurturing and calculated risks on the part of business people.

Whilst the integrated vision of UT as we imagined it has not yet come to fruition, the social media services which have flourished in the past 10 years have ended up straddling multiple spheres of life in surprising and unpredictable ways. Who would have foreseen the speed and depth to which services like Google Maps, Facebook and Twitter have penetrated into the daily lives of hundreds of millions of people, necessitating that government, education and business have all had to incorporate them into their standard procedures as well? What kinds of services and platforms will emerge over the next 10 years and how might we shape them beyond the rubrics and dictates of the marketplace?

Looking back I’m immensely proud of the scope and scale of our vision as well as what we achieved both in the original Urban Tapestries project, and how we carried it forward into the Social Tapestries programme. A core strength was our insistence on a social and cultural focus for the project, not placing the emphasis on the technology. It identified that the heart of these systems and services is ultimately about connecting us, enabling us to communicate in new and different ways: building and maintaining relationships to each other, to places and the things we encounter in them.

Our projects since have continued to explore these trajectories – enabling and encouraging people to have agency for themselves; to make and share their own stories, not simply to be cast in the role of the audience or consumer. Public Authoring remains a key concept that underpins our continuing work with communities as diverse as Pallion (Sunderland) and Reite (Papua New Guinea).

Download the report (PDF 2Mb)

Wearable Superpowers at Science Museum Late

June 2, 2015 by Giles Lane

Packed house for Wearable Superheroes at #smlates. Spot the odd ones out? pic.twitter.com/oeVkakNV3e

— David Robertson (@Davesci) April 29, 2015

A few weeks ago our Snout project costumes – Mr Punch and the Plague Doctor – had a rare outing to take part in a Late at the Science Museum in London. They were presented by students on UCL’s MA in Museum Studies as part of their group final show, We Need to Talk: Connecting Through Technology. We are told they were voted the audience favourite!

Thanks to Professor George Roussos at Birkbeck (for arranging and supporting) and to electronics engineer Demetrios Airantzis for building new power supplies for the wearable sensors, processor boards and LED displays – still working perfectly after 8 years.

Magna Carta 800 Set

May 26, 2015 by Giles Lane

June 2015 is the 800th anniversary of the signing of the Magna Carta – considered by many to be the keystone to Britain’s constitutional and democracy. Over the past six months I have been publishing a series of books – 6 in all – to celebrate the Magna Carta. Each book contains several texts from across the centuries that have been inspired by the Magna Carta: from the English Civil War era, to the French and American Bills of Rights in the late 1700s, the Chartists of the 1830s though to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, Charter88 and the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union of 2000. The final book in series contains Henry I’s Charter of Liberties (1100) on which the Magna Carta itself is based, the original 1215 Magna Carta and the Charter of the Forests of 1217.

What the series shows is a lineage stretching back to Saxon times of the struggle to assert and protect the inherent rights and dignities of ordinary people against the attempts by the wealthy and powerful to control and corral resources, assets and power for themselves, at the expense of everyone else.

These books have all been distributed as part of bookleteer‘s monthly subscription service, the Periodical, with the final book being distributed in June 2015. I have saved 40 copies of each which have been bound together with red satin ribbon in a special edition, which are now available to pre-order from our online store.

Each set costs £20 plus postage and packing: buy your’s here.

View the whole collection here – free to read online or download, print out and make up yourself.

Soho Memoirs Set

May 21, 2015 by Giles Lane

Last year we collaborated with The Museum of Soho to publish three memoirs by Soho residents from their archives. Each is a poignant recollection of Soho’s yesteryear, of lives lived and worked there. The books were originally distributed as part of bookleteer‘s monthly subscription service, the Periodical, and at a special MoSoho event host by the House of St Barnabas. We’ve put a small number aside and created a special edition of 32, each set wrapped in traditional brown paper reminiscent of a naughtier age, when Soho was a byword for difference and danger.

The sets cost £20 each plus postage & packing. Visit our online store and buy your’s here.

Bookleteering on the Rai Coast of Papua New Guinea

March 22, 2015 by Giles Lane

Today is the last day of our fieldwork in Papua New Guinea. I’ve been here for the past 3 weeks or so with anthropologist James Leach piloting the first stage of a new kind of toolkit designed to help remote indigenous communities document and record – in their own hand and forms of expression – the kinds of traditional cultural, environmental, ecological and social knowledge (“TEK”) that are in danger of gradually fading away as development, resource extraction, industrialisation and the money economy erode their ability to live sustainably in the bush/jungle.

I flew to Perth in late February to spend a week with James preparing for our trip : gathering the gear we’d need to be able to co-design booklets using bookleteer offline in the bush, print them out and scan them back in, as well as documenting all these processes. James is currently on an ARC Future Fellowship at the University of Western Australia, as well as Professor and Director of Research for the French Pacific Research Institute, CREDO in Marseille. He has been working with the people of Reite village on Papua New Guinea’s Rai Coast (Madang Province) since 1993 and his 2003 book, Creative Land (Berghahn Books), is a major anthropological study of their culture and society. James and I have been collaborating on ideas of self-documentation of traditional knowledge and “indigenous science” ever since I introduced him to the Diffusion eBook format and bookleteer back in 2008. When two Reite people, Porer Nombo and Pinbin Sisau, came to the UK in 2009 to take part in a project at the British Museum’s Ethnographic Dept telling stories and giving information about hundreds of objects from PNG in the collection, we first used the notebooks together to create a parallel series of documents about this encounter and what was revealed.

In 2012 I was invited to share my thoughts on how bookleteer and the books format could be used by indigenous people themselves at the Saem Majnep Memorial Symposium on TEK at the University of Goroka in PNG. We followed this up with a trip to Reite village where we spent a week testing out our ideas with people from the village, and developing a simple co-design process for creating notebooks with prompts to help people (whose literacy varies dramatically) record and share things of value to them. The focus was to understand how far this idea could really deliver something of use and value to people who live a largely traditional way of life in the bush, and why they might want to do this. It became clear early on that the enormous enthusiasm was driven by concerns about how all the knowledge that has allowed their society to thrive in the bush for countless generations could easily vanish in the face of money, cash cropping and the speed of communications and change that factors like mobile phones are bringing – leading some young people to turn away from traditional life for the dubious advantages of a precarious life in the shanty towns on the edge of PNG’s growing cities. The notebooks offer a new kind of way to preserve and transmit such knowledge for future generations, especially as they combine the physical and the digital, meaning the loss of a physical copy of a book doesn’t matter when it has been digitised and stored online. The success of this first experiment enabled us to write a proposal for funding a 2 year pilot to the Christensen Fund (a US-based foundation) which awarded us funding in 2014.

After a brief stopover in Canberra to consult and share ideas with Colin Filer and Robin Hide of Australian National University (both PNG experts of longstanding), we headed straight to Madang to meet with James’ friend Pinbin Sisau (at whose home we would be staying in Reite village) and gather all the necessary stores to sustain us in the field for several weeks. After a day in Madang we took a dinghy, skippered by the ever-reliable Alfus, across Astrolabe Bay and South-East 60km or so along the Rai Coast to the black sand beach where we landed and were met by some villagers who’d help portage all our cargo the 10km inland we’d have to walk, up into the foothills of the Finisterre Mountains where Reite village is located (at about 300m above sea level).

James had visited Reite again recently, in October 2014, to discuss the upcoming field work and to gather more feedback on our original experiment so we could plan how, in practice, we could co-design notebook templates with the villagers and what we could prepare in advance to help this. A few small tweaks to prompts used in our 2012 co-designed notebook were made, as well as creating a simple printed version (I had handwritten all the notebooks we used before) on bookleteer and a new book for collective writing. To have the capability to design, generate and print out bookleteer books in the field, I commissioned Joe Flintham (Fathom Point Ltd) – who is bookleteer’s chief consultant programmer – to adapt a version of bookleteer to run offline (i.e. with no need for internet connectivity) on my Apple MacBook Air laptop. Joe created an Ubuntu Virtual Machine image of bookleteer (minus various online services) that runs on Oracle’s Virtual Box application. Combining this with a portable inkjet printer (a Canon Pixma iP110 with battery), a portable scanner (an EPSON DS-30) and the Polaroid PoGo & LG Pocket Photo PD239 Zink printers would give us a fully-fledged ‘bush publishing” capability. For paper we brought with us a supply of Aquascribe waterproof paper (a Tyvek-type product) and pre-printed and shipped some 170 copies of different book templates. The waterproof paper is a highly useful technology to use in the damp and humid environment, where ordinary pulp-based paper becomes fibrous very swiftly and disintegrates in a short time. Books printed and made on this paper (as we used before) have a much longer lifespan – possibly decades.

Reite is made up of several hamlets, being the name applied not just to one village but an administrative district from the colonial period. As such the people who took part in our project come not just from Reite itself, but from Sarangama, Yasing, Marpungae and Serieng. For the next two weeks of our fieldwork we were constantly engaged in discussions with local people about the books, what they might include in them and how they could help reinforce the importance of the knowledge of the land, plants, animals and environment that people here have developed over generations. Once again, James’ long-term collaborator and informant, Porer Nombo, was the hub around which much of the necessary energy to bring people together and discuss the ideas was focused. In addition to the 3 templates we had prepared before coming, we co-designed with Porer, Pinbin and several others with a keen interest (such as Peter Nombo and Katak Pulu) another 4 different styles of notebook for a range of different themes and types of ‘stori’ that people wanted to record. Overall, 63 books were completed by around 42 people during the fortnight we stayed in the village. The major difference in this project was that, rather than taking the books away to scan and return, the portable scanner meant that we could scan everyone’s book in the village itself. Thus we could store a digital copy (and print out another if needed) and leave the original in its author’s hands in the village. This was an important step, partly to underscore that the books were by and for people in the village, not for us, and also to counter ideas that we might be taking knowledge away from the village to profit from selling it. For us, the digitisation of the books is a critical component for transmission to the future as it means that the unique books, which are hand written and drawn in by their authors, can be retrieved and printed again if lost or damaged. We explained this to everyone in several meetings – both smaller ones within the house we stayed in, and a larger public meeting about halfway through the project.

As in our previous experiment, we designed the front cover of each book to include a photograph of the author (which we took using digital cameras and our smartphones and printed out on the sticky-backed photo paper of the PoGo & LG Zink printers). As well as describing the general themes of the prompts inside each book, the cover also includes the simple statement that the author has been told about and understands the project, as well as statements (which they can cross out if they don’t agree to) that the book can be scanned onto computer, and shared online. As it turned out, the excitement that people’s work would appear on the internet was palpable and a significant impetus behind participation. Having something they had made, with their picture on it, on the internet had real value – suggesting that the knowledge they have could both be seen by others around the world and known about across PNG too.

What became one of the most important aspects of the fieldwork was the way that the local primary school (St Monica’s Reite) adopted the books wholesale and wove them directly into the curriculum around social science and environmental studies. We met up with Mr Jonathan Zorro, the school headmaster, in the first days of our trip (I had met him on my previous trip and James again last October) and he confirmed that he was very keen for the school to become involved. It turned out that the school has a desktop PC with a laser printer and scanner, so it became clear that not only could the school print out copies of the books on standard A4 paper, but they could scan them in and store them locally on the school computer. We agreed to spend a day at the school to introduce the project to all the students and then to do some practical book-making demonstrations and workshops with each class. James also agreed to give each of the Upper school classes (years 5-8) a short lecture on the importance of traditional knowledge and how it relates to environmental studies and preserving the community’s way of life. Mr Zorro organised for 290 books to be printed at the school, with one of the key emphases being that the students should use both the Tok Pisin versions and the English versions to improve their language and descriptive skills. Mr Zorro kindly shared with us the assessment criteria which he also developed for the students’ work : assessing their English language skills, their artwork (drawing), narrative ability, use of social science and environmental studies knowledge. Within a week of our first presentation at the school many of the students had submitted books of their own and we ended up digitising 55 of the best ones.

We had planned for a visit by to Reite by Catherine Sparks (who is based in Vanuatu) and Yat Paol (based in PNG) from the Christensen Fund’s Melanesian programme, but Cyclone Pam intervened and our own visit to the village was cut short by a few days (due to some health and security issues) so we have ended up completing our fieldwork from a base in Madang. There we presented the work completed to Yat Paol and were also able to arrange a meeting for him with the school headmaster plus Porer Nombo and Pinbin Sisau who have been our steadfast colleagues in this project. Now we have scanned the 118 books we have been indexing their contents and details of the authors to prepare a specially designed website to act as an online repository of library for Reite, and beginning to analyse and work with Porer and Pinbin on some indigenous classifications for the kinds of knowledge and experience that they contain. As our time here draws to a close we find that we have a wealth of stories to develop new parts of the toolkit from, and a clear sense of direction for the project’s second stage.

Discovering Bikes and Bloomers

June 4, 2014 by aliceangus

Over the last few weeks I have been drawing and painting a series works to be printed on silk and wool for a set of unique textile linings for Victorian ladies cycling garments; commissioned for the Freedom of Movement research project created by sociologist Katrina Jungnickel who is based at Goldsmiths, University of London. The drawings are inspired by Kats in-depth research and tell some of the stories behind each patent, the woman who invented it and the social, technological, physical and cultural challenges that early women cyclists had to face .

Through much of my work with Proboscis collaborating with communities, geographers, technologists and social scientists I’ve become interested in how drawing in public or amongst researchers can be a catalyst for conversation, observation and new analysis, revealing hidden connections and sparking alternative ways to interpret ideas and research. So, rather than being isolated from Kats research in my studio I decided to take the work to Kat’s space in the Sociology Department at Goldsmiths, and for the conversation this sparked to inform the content and feel of each drawing as it developed. Kat has a keen interest in making, craft and collaboration so at any time there was drawing, sewing, film-making, photography and desk based academic research all going on in the space. The finished linings are the a record of, and result of those intense drawing activities as well as an interpretation of the research.

One of the features of the cycling garments that attracted me to this project is that they convert from one type of garment to another. A long skirt might be folded, gathered or lifted up to above the knee by some mechanism of cords, buttons or hooks, to reveal bloomers worn underneath or perhaps a long coat on top; in another patent a skirt is taken off, to reveal bloomers, and worn as a cycling cape. In previous projects I’ve explored drawing and textiles, creating images that change or are revealed by the movement of the fabric so it was interesting to now do this with such rich research tied to the form of a historical garment and in conversation with the researcher and her team.

I was surprised to find out how controversial it was for women to cycle (particularly wearing bloomers), they were shouted and jeered at, refused entry to cafes, were socially shunned and had dirt thrown at them. The women who invented these garments had to be highly creative and balance the need for modesty with the need for free movement of the limbs and safety from fabric catching in the mechanism of the bicycle. Despite the privileged backgrounds of the very early cyclists (machines were expensive) I think these women must have had to display great courage and strength of purpose to push against convention, adopting and campaigning for women’s freedom to be accepted as cyclists, to race on cycles and wear clothing that allowed them more freedom.

The garments themselves will be worn and used for storytelling and presenting the research. You can see them in an exhibition at Look Mum No Hands from 7pm on the 13 June 2014 find out more at bikesandbloomers.com

Spring Update: what we are up to

May 20, 2014 by Giles Lane

Over the past six months or so we have been developing some new partnerships and working on several collaborative projects:

Alice is collaborating with Dr Katrina Jungnickel of Goldsmiths College’s Department of Sociology (and a former Proboscis associate from earlier days) on the Bikes and Bloomers project. She has been creating a series of illustrations – inspired by Katrina’s research into early women’s cycling clothes and the “rational dress” movement – which are being digitally printed on fabrics as part of recreations of some of the early designs for freedom of movement in clothing.

Alice has also received an Artist in Residence award to collaborate with the Mixed Reality Lab at the University of Nottingham on their Aestheticodes project, embedding smart codes for visual recognition into drawings and exploring the properties of working with printed fabrics for physical and digital storytelling.

Giles has been continuing to select works from bookleteer for our monthly subscription service, the Periodical – ranging this year from a tactile history of an ancient Scottish kingdom, to works of new poetry and fiction, memoirs of growing up in Soho in the 1920 and 30s, to a republication of John Milton’s 1644 call for unlicensed printing (and a free press), Areopagitica. He is also running a series of Pop Up Publishing workshops in May for the LibraryPress project, introducing new people to bookleteer and self-publishing in public libraries in Hounslow, Islington & Wembley.

Giles has recently been collaborating with the Movement Science Group at Oxford Brookes University who are leading on the development of a Rehabilitation Tool for survivors of traumatic brain injury (TBI), which is being funded by the EU as part of the CENTER-TBI project.

Giles has also been developing a new collaboration with the ExCiteS (Extreme Citizen Science) research group at UCL to bring together the work he has been doing with Professor James Leach and the community of Reite in Papua New Guinea on Traditional Environmental and Cultural Knowledge (TEK), with ExCiteS work with forest-dwelling communities in Congo and elsewhere. We aim to develop a prototype for indigenous people to be able to digitally record and share knowledge using a combination of machine learning software, mobile devices and their own traditional craft and cultural practices. This is being developed alongside our planning for further field work in PNG to expand upon our pilot TEK toolkit experiments using hybrid digital/physical notebooks formats.

Visualise: Making Art in Context

January 20, 2014 by Giles Lane

Anglia Ruskin University has published a book, edited by Bronac Ferran, reflecting on the Visualise public art programme. We have contributed a short piece describing our Lifestreams collaboration with Philips Research.

Visualise: Making Art in Context

Published by Anglia Ruskin University

Edited by Bronac Ferran

Designed by Giulia Garbin

ISBN: 978-0-9565608-6-5

Published 28th November 2013

Copies can be ordered from : Pam Duncan, Bibliographic Services Manager, University Library, Anglia Ruskin University

The book brings together essays by artists featured in the Visualise public art programme, which took place from Autumn 2011-Summer 2012 across Cambridge, managed by Futurecity with guest curator Bronac Ferran. It includes reflections on the development of the programme by Professor Chris Owen Head of Cambridge School of Art and from Andy Robinson of Futurecity on the role artists can play in our cities ecology and contested public realm. Among the essays are newly commissioned pieces relating to poetry, composition, music, code, language and place by Liliane Lijn, Eduardo Kac, Tom Hall, Alan Sutcliffe and Ernest Edmonds as well as interviews with Duncan Speakman and William Latham, reflections on two art and industry collaborations by Bettina Furnee and Dylan Banarse, and Giles Lane of Proboscis and David Walker of Philips Research and a previously unpublished holograph by Gustav Metzger.

About Visualise: Making Art in Context

From tales of a transgenic green bunny to a singing painting, from computer-generated lifecharms to a soundwalk at dusk through Cambridge’s streets, parks and arcades, this publication conveys some of the myriad happenings which characterised Visualise; a programme of public art, curated for Anglia Ruskin University in 2012. Funded by the University from Percent for Art sources, Visualise brought new life to hard streets, providing opportunities for public engagement through challenging visual art and sound installations, temporary events and exhibitions. It connected in direct and indirect ways to perceptions of Cambridge as context and site of scientific discovery and technological inventiveness. The book weaves the history of Cambridge School of Art and the Ruskin Gallery (the place where Syd Barrett of Pink Floyd played his first gig and Gustav Metzger, renowned founder of auto-destructive art, had his first arts education before the end of the Second World War) with today’s digital developments. A series of newly commissioned essays provide intriguingly personal insight into how world-leading international and local artists create lasting ‘mark and meaning’ (Eduardo Kac) working in contexts of historical time as well as in physical space.

StoryMaker PlayCubes

November 16, 2013 by Giles Lane

StoryMaker is a set of 9 playcubes (1 of 3 sets from Outside The Box) that incite the telling of fantastical tales. Roll the three control cubes to decide how to tell your story, what kind of story it should be and where to set it. Then use the six word cubes as your cue to invent a story on the spot. Each set comes flatpacked with a PlayGuide booklet. You can browse all the cubes and the play guide on bookleteer.

Make up stories on your own or with friends. Challenge your storymaking skills with the Genre, Context and Method cubes to suggest what type of story you can tell, what time or place it is set in and how you’re going to tell it. Use the Word cubes to make the game even more fun: choose one set of words to tell you story with, or combine different sets to make up longer stories or more complex games.

Earlier this year we printed up a small edition of the StoryMaker PlayCubes which are now available to purchase. If you’d like a set then please order below or visit our web store for other options.

|

StoryMaker PlayCubes Set

9 PlayCubes + PlayGuide Booklet |

||

|

United Kingdom

|

European Union

|

USA/Rest of the World

|

|

£25

(inc VAT & p+p) |

£30

(inc VAT &p+p) |

£35

(inc p+p) |

|

use PayPal below

|

use PayPal below

|

|

|

Pay with Paypal

|

||

Thoughts on failure

November 13, 2013 by Giles Lane

This week we failed to reach our kickstarter goal for the PlayCubes project. And not by a small margin: at the close of play we had only reached 13% of our goal – just £528 out of £4,000. So I find myself asking, “What does it mean to have failed?”

The campaign was an experiment to see if this form of fundraising could work for us. It was ‘low risk’ in the sense that we were not raising funds for a new project, but to complement an already finished one with an additional outcome. It is certainly disappointing not to be able to manufacture the sets and get them out into the world as we planned; there are clearly things we can look at and consider changing such as reward types, pledge amounts and even the physical form of the PlayCubes. But do these issues indicate why the campaign failed or could there be other reasons?

Tim Wight wrote an excellent post a few weeks ago on innovation and failure which I have been thinking about during the campaign and especially once it became clear we would be unlikely to reach our target (essentially after the fifth day of a two week campaign). Tim has some great observations about the way failure is perceived and addressed culturally; how so often people seek to ‘recuperate’ failure by turning it into a risk-averse ‘learning’ opportunity rather than accepting failure as is, as something intrinsic to the creative process.

“I’d argue, however, that we don’t always have to learn from failure, and that sometimes making the same mistakes over and over again might even be part of the innovation (or rather the *invention*) process.”

What can I learn from this process? Is there anything, in fact, worthwhile to learn? Did the project “fail” or is it that I didn’t “sell” it well enough? Is it a failure of concept, execution or communication?

“…failure doesn’t necessarily need to have a learning point or any value.

We can just noodle about and experiment and repeat and fail again and again and again without any obvious point. Many great artists have done this. “

As I’m sure others who’ve launched kickstarter projects have experienced, I received a number of messages offering me advice and professional services to enhance the campaign. Essentially all the advice boiled down to a simple nugget, that the only way to succeed was to already have a significant “fanbase” who could be “activated” or motivated to pledge support and then amplify it by sharing the fact they’d supported the project to their friends and social circles. If I’ve learnt anything then its probably that Proboscis doesn’t have a fanbase as such to activate.

The irony, too, was not lost on me of trying to raise funding for a project about free play and improvisation without rules, winners or rewards on a crowdfunding platform entirely structured around rewards and goals – where there are only winners (those who reach or surpass their goal) and losers. Could there be more to this than just irony? Could it be that the conceptual nature of the PlayCubes (indeed of my whole practice) is just so diametrically opposite to the way in which kickstarter and the communities which form around it operate that it was always unlikely to succeed? Tim’s post also quotes Tom Uglow writing about a project they collaborated on, #dream40

“Artistic projects like this do not fit one-size-fits all metrics; and I’m not sure what those metrics are anyway – though I do know that targets breed strategies to hit targets, so you’ll forgive us for ignoring them. Hitting targets reward organizations not audiences, or artists, or culture.”

Tom Uglow, Google Creative Labs

This leads me to think about consumption and how kickstarter reflects an ideal of a free market economy, a sort of microcosm of how free markets are supposed to work, albeit in a very basic form. As an artist I have spent my whole career trying to evade the normalising effect of being part of such an economy – most likely as a product of growing up in the 1980s during the Thatcher years. My work has always been about exploring what’s beyond the horizon, of trying to anticipate the things that are just out of our reach, that are outwith the contemporary boundaries of society and culture. So much of what we’ve done at Proboscis since around 2000 has also been forward looking, about inventing new futures. The kinds of social and cultural ideas, tools and techniques we’ve created have often been ahead of their time: testing the just-possible and directing attention at where things could go. Is there perhaps a contradiction in using the logic of consumption and popularity to support projects that are precisely not popular because what underlies them is unfamiliar, perhaps even uncomfortable – something that may not become mainstream for years?

“Even more importantly, people generally don’t learn from other people’s mistakes. They’d much rather learn from their *own* mistakes. Your own mistakes hurt so much more and live with you much longer. It doesn’t matter how often Mummy or Daddy tell you not to put your hand near the fire, you’ll only really remember not to do it *after* you’ve burned your hand, right?”

Despite our kickstarter campaign failing, I feel unrepentant. I’m going to keep getting my hand burnt in this way because I believe that what Proboscis does is genuinely valuable – despite the dearth of pledges we’ve had plenty of positive feedback about the PlayCubes. We find ourselves, like many others, struggling to keep afloat in challenging times, but persistent, dogged in continuing to make work and to make a difference. Like the spider Robert the Bruce famously watched trying to weave a web across a cave entrance, even though it kept falling down, it kept on trying until at last it succeeded – “If at first you don’t succeed, try try and try again.”

“Ever tried. Ever failed. No matter. Try again. Fail again. Fail better.”

Samuel Beckett, Worstward Ho

We’ll keep trying, fail again and again, but fail better.

PlayCubes Film

November 5, 2013 by Giles Lane