Reflecting on Urban Tapestries

July 6, 2015 by Giles Lane · 7 Comments

Ten years ago we published Public Authoring, Place and Mobility – a report on the Urban Tapestries project (2002-04) which brought together all that we had learned, described our methodologies and activities, evaluated our achievements and presented a series of policy proposals. I have been re-reading it to see how well our ideas have held up over the past decade, and to what extent they have been borne out by the development of social media, the mass adoption of smartphones and connected devices, and by social and cultural behaviours.

Urban Tapestries was conceived in June 2002, just after we had completed another project, Private Reveries, Public Spaces (2001-02), which explored the social and cultural impact of the emerging mobile communications revolution. We started to imagine what the effects would be on how people inhabit urban space once the physical topography of the city could be overlaid with an invisible data landscape accessible via mobile devices. Such “location based services” were then only in their infancy (in places like Japan via DoCoMo’s i-mode service) and nearly all the academic and industry research projects of the time focused on their potential use as tourist guides.

Urban Tapestries set out to imagine and investigate the everyday – how might people use them in everyday life: on the way to work or school, going to the supermarket, visiting the doctor, socialising or playing in a park. Funded through an unusual public/private mix, the project set out to peer into the future ten years or so ahead. We sought to articulate a vision that was grounded in actual social situations and cultural behaviours, and not just to rely on imagined scenarios and invented personas.

The report contains a wealth of observations and insights gained from our iterative and participatory process. We combined paper prototyping with social engagement, user trials of functioning systems in public settings as well as numerous public workshops and events where we shared and discussed our ideas as the project progressed. Below are some of the policy proposals which we made back in 2005 along with some comments on how the ideas behind them fare in 2015.

We followed UT with a 5 year programme of projects called Social Tapestries (2004-09), where we sought even further to embed our research in actual communities and situations. Through a series of discrete projects we explored our concepts of public authoring and social knowledge in ways that prefigured many of today’s familiar tropes : wearable sensors and citizen science, civic engagement and participation, big urban data and environmental mapping, hybrid digital/physical interfaces, robotics and hacking, to name a few. In these we sought extend and deepen the insights, working with real communities in actual places to explore what opportunities could become realities.

- Innovation from the margins to the centre

Governments, researchers and businesses need to pay greater attention to the needs of actual people in real contexts and situations rather than relying on marketing scenarios and user profiles.

Co-design and co-creation techniques along with iterative and agile development processes have become commonplace, especially through the concept of minimum viable product as a means of fast and iterative development of new products and services. Although not ubiquitous, they are far more likely to be present in the development of services that engage people, from the grassroots to industry, commerce and government. If this trend continues it bodes well for the role of the actual people in the design, testing and implementation processes of services intended for them. - Open Networks for Mobile Data

Telecom network operators need to recognise the desires of people to communicate (by voice or data) with each other irrespective of the company they purchase their service from.

Its hard to think back to a time when mobile data was restricted to the network operators own “walled gardens”, but it was actually not so long ago. With recent changes to EU data roaming laws bringing down national barriers by 2018, a whole new wave of data mobility will be realised. ‘Net neutrality’ remains a contested standard though, as all kinds of network and service providers (not just mobile) increasingly converge their offers and seek to maximise revenues for high value content. - Open Geo Data

There is a clear and pressing need for free public access to GIS data to make public authoring and a host of other useful geo-specific services possible.

The growth of open mapping platforms like Openstreetmap as well as services like Google Maps and Google Earth made possible the rapid growth of user-created georeferenced projects and services in a short space of time. Yet the major owners of GIS data (such as Ordnance Survey) have only slowly and partially opened up their systems for free use by the public. The planned release of the UK’s entire LIDAR data in 2015 by Defra may be a signal moment in the shift from the proprietary model of mapping by the state towards a more democratic understanding of mapping a a civil process in its own right. - Reinvigoration of the Public Domain

Public authoring has the potential to be a powerful force in enriching the public domain through the sharing of information, knowledge and experiences by ordinary people about the places they live, work and play in.

Social media has exploded into the public realm and has arguably taken a significant role in facilitating entirely new ways for people to share what they know and experience, as well as to organise all manner of movements for action and change. People’s willingness to share with unknown others underlines the essential human quality that seeks to build new relationships, new communities wherever we go. In counterpoint, the Snowden revelations have given weight to concerns about the extent of state surveillance that circulated since the late 1990s (cf the Echelon network) and the degree to which free speech is inevitably curtailed by self-censorship when people are aware that their every utterance and communication may be intercepted at will, now or in the future. Nevertheless, our abilities to form new communities around ideas, campaigns, issues and passions have been continually advanced by the depth and speed that these forms of social media have enabled. - Public Services Engaging with People

Public authoring could be employed to create new relationships of trust and engagement between public services and the people they serve. Public authoring proposes a reciprocity of engagement whereby public services would not just provide information but benefit directly from information contributed by citizens.

Our ideal of new trusted, reciprocal engagement between citizens and public services has not quite emerged as we may have hoped, however there have been indications that such change is afoot, not least in the expanding area of open (public) data. That more public organisations are allowing others to access and use their data for their own purposes suggests hope for the future. There is much more that could be done to both increase transparency and to increase the role of citizens in the management of our communities. State surveillance is also a factor affecting people’s sense of agency and trust in governmental mechanisms that will have to be continually addressed as we shape the future of our democracies. - Market Opportunities

The wealth of public data created by public authoring will provide many market opportunities for business people and entrepreneurs. The not-for-profit sector needs to embrace the energy and creativity this engenders as much as the commercial sector needs to embrace the need for people to be more than just consumers.

The dividing lines between “public” and “private” have become ever more blurred in recent years. The impacts of austerities imposed since the 2008 banking collapse and subsequent ongoing economic turmoil have seen areas previously the preserve of the “public sector” outsourced to private enterprise under the guise of “efficiency” and profit. This was certainly not what we envisaged as it has imposed a narrow financial interpretation of value and excised almost all considerations other than the purely monetary from decision making. By transferring more and more of our public services in this way, the scope and legitimacy of democracy are undermined. We need to reaffirm other measures of value that have been pushed aside and stand firm for their re-adoption as standards to aim for so that we can indeed create diverse new opportunities in both “public” and “private” sectors. - Location Sensing & Positioning

The technological imperative for defining a person’s position needs to be dropped in favour of an approach that incorporates the rich nature of the physical world’s location information – street signs, shop signage etc.

Our insistence on not becoming entirely beholden to GPS, Glonass & Gallileo was perhaps a little brusque. However, there has also been a growing sense of discomfort with the purely digital. More and more people have become involved in making things: learning old manual skills that can be intertwined with newer digital ones. This hybrid digital/physical approach seems more and more plausible with each year. - Including Everyone

The drive to use the latest technologies and services must not exclude those who choose not to adopt them, or cannot, for whatever reason.

As with recent critiques of the Smart City concept, our emphasis in the report rested on active citizenship being at the heart of the potential opportunities being offered by these mobile, location enabled services. This necessitates including everyone in benefiting from the opportunities offered, not just restricting access to those able to afford to pay. There has been much debate over the intervening years about access to the internet having become effectively a utility needing the same statutory regulation as access to fixed-line telephones. If a government wants to engage its citizens on a “digital-first” basis, it must make sure that there is provision for others not able, for any reason, to access via other means – setting a standard that other services can emulate or aspire to. - Time and Relevance to Everyday Life

These new forms of communicating will not appear overnight but will need careful cultivation and time to flower. To realise their fullest potential they will need more than just grass roots enthusiasm and activism. They will require regulatory nurturing and calculated risks on the part of business people.

Whilst the integrated vision of UT as we imagined it has not yet come to fruition, the social media services which have flourished in the past 10 years have ended up straddling multiple spheres of life in surprising and unpredictable ways. Who would have foreseen the speed and depth to which services like Google Maps, Facebook and Twitter have penetrated into the daily lives of hundreds of millions of people, necessitating that government, education and business have all had to incorporate them into their standard procedures as well? What kinds of services and platforms will emerge over the next 10 years and how might we shape them beyond the rubrics and dictates of the marketplace?

Looking back I’m immensely proud of the scope and scale of our vision as well as what we achieved both in the original Urban Tapestries project, and how we carried it forward into the Social Tapestries programme. A core strength was our insistence on a social and cultural focus for the project, not placing the emphasis on the technology. It identified that the heart of these systems and services is ultimately about connecting us, enabling us to communicate in new and different ways: building and maintaining relationships to each other, to places and the things we encounter in them.

Our projects since have continued to explore these trajectories – enabling and encouraging people to have agency for themselves; to make and share their own stories, not simply to be cast in the role of the audience or consumer. Public Authoring remains a key concept that underpins our continuing work with communities as diverse as Pallion (Sunderland) and Reite (Papua New Guinea).

Download the report (PDF 2Mb)

Bookleteering on the Rai Coast of Papua New Guinea

March 22, 2015 by Giles Lane · 12 Comments

Today is the last day of our fieldwork in Papua New Guinea. I’ve been here for the past 3 weeks or so with anthropologist James Leach piloting the first stage of a new kind of toolkit designed to help remote indigenous communities document and record – in their own hand and forms of expression – the kinds of traditional cultural, environmental, ecological and social knowledge (“TEK”) that are in danger of gradually fading away as development, resource extraction, industrialisation and the money economy erode their ability to live sustainably in the bush/jungle.

I flew to Perth in late February to spend a week with James preparing for our trip : gathering the gear we’d need to be able to co-design booklets using bookleteer offline in the bush, print them out and scan them back in, as well as documenting all these processes. James is currently on an ARC Future Fellowship at the University of Western Australia, as well as Professor and Director of Research for the French Pacific Research Institute, CREDO in Marseille. He has been working with the people of Reite village on Papua New Guinea’s Rai Coast (Madang Province) since 1993 and his 2003 book, Creative Land (Berghahn Books), is a major anthropological study of their culture and society. James and I have been collaborating on ideas of self-documentation of traditional knowledge and “indigenous science” ever since I introduced him to the Diffusion eBook format and bookleteer back in 2008. When two Reite people, Porer Nombo and Pinbin Sisau, came to the UK in 2009 to take part in a project at the British Museum’s Ethnographic Dept telling stories and giving information about hundreds of objects from PNG in the collection, we first used the notebooks together to create a parallel series of documents about this encounter and what was revealed.

In 2012 I was invited to share my thoughts on how bookleteer and the books format could be used by indigenous people themselves at the Saem Majnep Memorial Symposium on TEK at the University of Goroka in PNG. We followed this up with a trip to Reite village where we spent a week testing out our ideas with people from the village, and developing a simple co-design process for creating notebooks with prompts to help people (whose literacy varies dramatically) record and share things of value to them. The focus was to understand how far this idea could really deliver something of use and value to people who live a largely traditional way of life in the bush, and why they might want to do this. It became clear early on that the enormous enthusiasm was driven by concerns about how all the knowledge that has allowed their society to thrive in the bush for countless generations could easily vanish in the face of money, cash cropping and the speed of communications and change that factors like mobile phones are bringing – leading some young people to turn away from traditional life for the dubious advantages of a precarious life in the shanty towns on the edge of PNG’s growing cities. The notebooks offer a new kind of way to preserve and transmit such knowledge for future generations, especially as they combine the physical and the digital, meaning the loss of a physical copy of a book doesn’t matter when it has been digitised and stored online. The success of this first experiment enabled us to write a proposal for funding a 2 year pilot to the Christensen Fund (a US-based foundation) which awarded us funding in 2014.

After a brief stopover in Canberra to consult and share ideas with Colin Filer and Robin Hide of Australian National University (both PNG experts of longstanding), we headed straight to Madang to meet with James’ friend Pinbin Sisau (at whose home we would be staying in Reite village) and gather all the necessary stores to sustain us in the field for several weeks. After a day in Madang we took a dinghy, skippered by the ever-reliable Alfus, across Astrolabe Bay and South-East 60km or so along the Rai Coast to the black sand beach where we landed and were met by some villagers who’d help portage all our cargo the 10km inland we’d have to walk, up into the foothills of the Finisterre Mountains where Reite village is located (at about 300m above sea level).

James had visited Reite again recently, in October 2014, to discuss the upcoming field work and to gather more feedback on our original experiment so we could plan how, in practice, we could co-design notebook templates with the villagers and what we could prepare in advance to help this. A few small tweaks to prompts used in our 2012 co-designed notebook were made, as well as creating a simple printed version (I had handwritten all the notebooks we used before) on bookleteer and a new book for collective writing. To have the capability to design, generate and print out bookleteer books in the field, I commissioned Joe Flintham (Fathom Point Ltd) – who is bookleteer’s chief consultant programmer – to adapt a version of bookleteer to run offline (i.e. with no need for internet connectivity) on my Apple MacBook Air laptop. Joe created an Ubuntu Virtual Machine image of bookleteer (minus various online services) that runs on Oracle’s Virtual Box application. Combining this with a portable inkjet printer (a Canon Pixma iP110 with battery), a portable scanner (an EPSON DS-30) and the Polaroid PoGo & LG Pocket Photo PD239 Zink printers would give us a fully-fledged ‘bush publishing” capability. For paper we brought with us a supply of Aquascribe waterproof paper (a Tyvek-type product) and pre-printed and shipped some 170 copies of different book templates. The waterproof paper is a highly useful technology to use in the damp and humid environment, where ordinary pulp-based paper becomes fibrous very swiftly and disintegrates in a short time. Books printed and made on this paper (as we used before) have a much longer lifespan – possibly decades.

Reite is made up of several hamlets, being the name applied not just to one village but an administrative district from the colonial period. As such the people who took part in our project come not just from Reite itself, but from Sarangama, Yasing, Marpungae and Serieng. For the next two weeks of our fieldwork we were constantly engaged in discussions with local people about the books, what they might include in them and how they could help reinforce the importance of the knowledge of the land, plants, animals and environment that people here have developed over generations. Once again, James’ long-term collaborator and informant, Porer Nombo, was the hub around which much of the necessary energy to bring people together and discuss the ideas was focused. In addition to the 3 templates we had prepared before coming, we co-designed with Porer, Pinbin and several others with a keen interest (such as Peter Nombo and Katak Pulu) another 4 different styles of notebook for a range of different themes and types of ‘stori’ that people wanted to record. Overall, 63 books were completed by around 42 people during the fortnight we stayed in the village. The major difference in this project was that, rather than taking the books away to scan and return, the portable scanner meant that we could scan everyone’s book in the village itself. Thus we could store a digital copy (and print out another if needed) and leave the original in its author’s hands in the village. This was an important step, partly to underscore that the books were by and for people in the village, not for us, and also to counter ideas that we might be taking knowledge away from the village to profit from selling it. For us, the digitisation of the books is a critical component for transmission to the future as it means that the unique books, which are hand written and drawn in by their authors, can be retrieved and printed again if lost or damaged. We explained this to everyone in several meetings – both smaller ones within the house we stayed in, and a larger public meeting about halfway through the project.

As in our previous experiment, we designed the front cover of each book to include a photograph of the author (which we took using digital cameras and our smartphones and printed out on the sticky-backed photo paper of the PoGo & LG Zink printers). As well as describing the general themes of the prompts inside each book, the cover also includes the simple statement that the author has been told about and understands the project, as well as statements (which they can cross out if they don’t agree to) that the book can be scanned onto computer, and shared online. As it turned out, the excitement that people’s work would appear on the internet was palpable and a significant impetus behind participation. Having something they had made, with their picture on it, on the internet had real value – suggesting that the knowledge they have could both be seen by others around the world and known about across PNG too.

What became one of the most important aspects of the fieldwork was the way that the local primary school (St Monica’s Reite) adopted the books wholesale and wove them directly into the curriculum around social science and environmental studies. We met up with Mr Jonathan Zorro, the school headmaster, in the first days of our trip (I had met him on my previous trip and James again last October) and he confirmed that he was very keen for the school to become involved. It turned out that the school has a desktop PC with a laser printer and scanner, so it became clear that not only could the school print out copies of the books on standard A4 paper, but they could scan them in and store them locally on the school computer. We agreed to spend a day at the school to introduce the project to all the students and then to do some practical book-making demonstrations and workshops with each class. James also agreed to give each of the Upper school classes (years 5-8) a short lecture on the importance of traditional knowledge and how it relates to environmental studies and preserving the community’s way of life. Mr Zorro organised for 290 books to be printed at the school, with one of the key emphases being that the students should use both the Tok Pisin versions and the English versions to improve their language and descriptive skills. Mr Zorro kindly shared with us the assessment criteria which he also developed for the students’ work : assessing their English language skills, their artwork (drawing), narrative ability, use of social science and environmental studies knowledge. Within a week of our first presentation at the school many of the students had submitted books of their own and we ended up digitising 55 of the best ones.

We had planned for a visit by to Reite by Catherine Sparks (who is based in Vanuatu) and Yat Paol (based in PNG) from the Christensen Fund’s Melanesian programme, but Cyclone Pam intervened and our own visit to the village was cut short by a few days (due to some health and security issues) so we have ended up completing our fieldwork from a base in Madang. There we presented the work completed to Yat Paol and were also able to arrange a meeting for him with the school headmaster plus Porer Nombo and Pinbin Sisau who have been our steadfast colleagues in this project. Now we have scanned the 118 books we have been indexing their contents and details of the authors to prepare a specially designed website to act as an online repository of library for Reite, and beginning to analyse and work with Porer and Pinbin on some indigenous classifications for the kinds of knowledge and experience that they contain. As our time here draws to a close we find that we have a wealth of stories to develop new parts of the toolkit from, and a clear sense of direction for the project’s second stage.

Discovering Bikes and Bloomers

June 4, 2014 by aliceangus · 2 Comments

Over the last few weeks I have been drawing and painting a series works to be printed on silk and wool for a set of unique textile linings for Victorian ladies cycling garments; commissioned for the Freedom of Movement research project created by sociologist Katrina Jungnickel who is based at Goldsmiths, University of London. The drawings are inspired by Kats in-depth research and tell some of the stories behind each patent, the woman who invented it and the social, technological, physical and cultural challenges that early women cyclists had to face .

Through much of my work with Proboscis collaborating with communities, geographers, technologists and social scientists I’ve become interested in how drawing in public or amongst researchers can be a catalyst for conversation, observation and new analysis, revealing hidden connections and sparking alternative ways to interpret ideas and research. So, rather than being isolated from Kats research in my studio I decided to take the work to Kat’s space in the Sociology Department at Goldsmiths, and for the conversation this sparked to inform the content and feel of each drawing as it developed. Kat has a keen interest in making, craft and collaboration so at any time there was drawing, sewing, film-making, photography and desk based academic research all going on in the space. The finished linings are the a record of, and result of those intense drawing activities as well as an interpretation of the research.

One of the features of the cycling garments that attracted me to this project is that they convert from one type of garment to another. A long skirt might be folded, gathered or lifted up to above the knee by some mechanism of cords, buttons or hooks, to reveal bloomers worn underneath or perhaps a long coat on top; in another patent a skirt is taken off, to reveal bloomers, and worn as a cycling cape. In previous projects I’ve explored drawing and textiles, creating images that change or are revealed by the movement of the fabric so it was interesting to now do this with such rich research tied to the form of a historical garment and in conversation with the researcher and her team.

I was surprised to find out how controversial it was for women to cycle (particularly wearing bloomers), they were shouted and jeered at, refused entry to cafes, were socially shunned and had dirt thrown at them. The women who invented these garments had to be highly creative and balance the need for modesty with the need for free movement of the limbs and safety from fabric catching in the mechanism of the bicycle. Despite the privileged backgrounds of the very early cyclists (machines were expensive) I think these women must have had to display great courage and strength of purpose to push against convention, adopting and campaigning for women’s freedom to be accepted as cyclists, to race on cycles and wear clothing that allowed them more freedom.

The garments themselves will be worn and used for storytelling and presenting the research. You can see them in an exhibition at Look Mum No Hands from 7pm on the 13 June 2014 find out more at bikesandbloomers.com

StoryMaker PlayCubes

November 16, 2013 by Giles Lane · 4 Comments

StoryMaker is a set of 9 playcubes (1 of 3 sets from Outside The Box) that incite the telling of fantastical tales. Roll the three control cubes to decide how to tell your story, what kind of story it should be and where to set it. Then use the six word cubes as your cue to invent a story on the spot. Each set comes flatpacked with a PlayGuide booklet. You can browse all the cubes and the play guide on bookleteer.

Make up stories on your own or with friends. Challenge your storymaking skills with the Genre, Context and Method cubes to suggest what type of story you can tell, what time or place it is set in and how you’re going to tell it. Use the Word cubes to make the game even more fun: choose one set of words to tell you story with, or combine different sets to make up longer stories or more complex games.

Earlier this year we printed up a small edition of the StoryMaker PlayCubes which are now available to purchase. If you’d like a set then please order below or visit our web store for other options.

|

StoryMaker PlayCubes Set

9 PlayCubes + PlayGuide Booklet |

||

|

United Kingdom

|

European Union

|

USA/Rest of the World

|

|

£25

(inc VAT & p+p) |

£30

(inc VAT &p+p) |

£35

(inc p+p) |

|

use PayPal below

|

use PayPal below

|

|

|

Pay with Paypal

|

||

Thoughts on failure

November 13, 2013 by Giles Lane · 6 Comments

This week we failed to reach our kickstarter goal for the PlayCubes project. And not by a small margin: at the close of play we had only reached 13% of our goal – just £528 out of £4,000. So I find myself asking, “What does it mean to have failed?”

The campaign was an experiment to see if this form of fundraising could work for us. It was ‘low risk’ in the sense that we were not raising funds for a new project, but to complement an already finished one with an additional outcome. It is certainly disappointing not to be able to manufacture the sets and get them out into the world as we planned; there are clearly things we can look at and consider changing such as reward types, pledge amounts and even the physical form of the PlayCubes. But do these issues indicate why the campaign failed or could there be other reasons?

Tim Wight wrote an excellent post a few weeks ago on innovation and failure which I have been thinking about during the campaign and especially once it became clear we would be unlikely to reach our target (essentially after the fifth day of a two week campaign). Tim has some great observations about the way failure is perceived and addressed culturally; how so often people seek to ‘recuperate’ failure by turning it into a risk-averse ‘learning’ opportunity rather than accepting failure as is, as something intrinsic to the creative process.

“I’d argue, however, that we don’t always have to learn from failure, and that sometimes making the same mistakes over and over again might even be part of the innovation (or rather the *invention*) process.”

What can I learn from this process? Is there anything, in fact, worthwhile to learn? Did the project “fail” or is it that I didn’t “sell” it well enough? Is it a failure of concept, execution or communication?

“…failure doesn’t necessarily need to have a learning point or any value.

We can just noodle about and experiment and repeat and fail again and again and again without any obvious point. Many great artists have done this. “

As I’m sure others who’ve launched kickstarter projects have experienced, I received a number of messages offering me advice and professional services to enhance the campaign. Essentially all the advice boiled down to a simple nugget, that the only way to succeed was to already have a significant “fanbase” who could be “activated” or motivated to pledge support and then amplify it by sharing the fact they’d supported the project to their friends and social circles. If I’ve learnt anything then its probably that Proboscis doesn’t have a fanbase as such to activate.

The irony, too, was not lost on me of trying to raise funding for a project about free play and improvisation without rules, winners or rewards on a crowdfunding platform entirely structured around rewards and goals – where there are only winners (those who reach or surpass their goal) and losers. Could there be more to this than just irony? Could it be that the conceptual nature of the PlayCubes (indeed of my whole practice) is just so diametrically opposite to the way in which kickstarter and the communities which form around it operate that it was always unlikely to succeed? Tim’s post also quotes Tom Uglow writing about a project they collaborated on, #dream40

“Artistic projects like this do not fit one-size-fits all metrics; and I’m not sure what those metrics are anyway – though I do know that targets breed strategies to hit targets, so you’ll forgive us for ignoring them. Hitting targets reward organizations not audiences, or artists, or culture.”

Tom Uglow, Google Creative Labs

This leads me to think about consumption and how kickstarter reflects an ideal of a free market economy, a sort of microcosm of how free markets are supposed to work, albeit in a very basic form. As an artist I have spent my whole career trying to evade the normalising effect of being part of such an economy – most likely as a product of growing up in the 1980s during the Thatcher years. My work has always been about exploring what’s beyond the horizon, of trying to anticipate the things that are just out of our reach, that are outwith the contemporary boundaries of society and culture. So much of what we’ve done at Proboscis since around 2000 has also been forward looking, about inventing new futures. The kinds of social and cultural ideas, tools and techniques we’ve created have often been ahead of their time: testing the just-possible and directing attention at where things could go. Is there perhaps a contradiction in using the logic of consumption and popularity to support projects that are precisely not popular because what underlies them is unfamiliar, perhaps even uncomfortable – something that may not become mainstream for years?

“Even more importantly, people generally don’t learn from other people’s mistakes. They’d much rather learn from their *own* mistakes. Your own mistakes hurt so much more and live with you much longer. It doesn’t matter how often Mummy or Daddy tell you not to put your hand near the fire, you’ll only really remember not to do it *after* you’ve burned your hand, right?”

Despite our kickstarter campaign failing, I feel unrepentant. I’m going to keep getting my hand burnt in this way because I believe that what Proboscis does is genuinely valuable – despite the dearth of pledges we’ve had plenty of positive feedback about the PlayCubes. We find ourselves, like many others, struggling to keep afloat in challenging times, but persistent, dogged in continuing to make work and to make a difference. Like the spider Robert the Bruce famously watched trying to weave a web across a cave entrance, even though it kept falling down, it kept on trying until at last it succeeded – “If at first you don’t succeed, try try and try again.”

“Ever tried. Ever failed. No matter. Try again. Fail again. Fail better.”

Samuel Beckett, Worstward Ho

We’ll keep trying, fail again and again, but fail better.

PlayCubes Film

November 5, 2013 by Giles Lane · 5 Comments

PlayCubes : kickstarting the next stage

October 29, 2013 by Giles Lane · 1 Comment

Three years ago, not long after Mandy Tang started at Proboscis, we came up with an idea to use the StoryCubes and bookleteer to inspire people to play and invent their own games. We were inspired ourselves by the Love Outdoor Play campaign, which aims to encourage children, and their parents, to play outside more. Over about six months Mandy developed Outside The Box as a side-project within the studio, devising the three games with help from the team and illustrating all the resulting cubes. We frequently got together to test out the game ideas, as well as with friends and eventually with a group of children on a YMCA play scheme. But as the studio got stuck into several large projects, we didn’t get round to completing the whole package until recently.

The result is Outside The Box – a “game engine for your imagination” – designed to inspire you to improvise and play your own games on your own or with others, indoors or outside. It’s made up of 27 cubes, 3 layers of 9 cubes, each layer being a distinct game : Animal Match, Mission Improbable and StoryMaker. Outside The Box has no rules, nothing to win or lose, the cubes simply provide a framework for you to imagine and make up your own games. You can browse through the whole OTB collection of cubes and books on bookleteer, to download and make up at home.

However, 27 large PlayCubes and 7 books is a lot to make yourself, so we’re now planning to manufacture a “first edition” to get them into people’s hands to find out what they do with them. To achieve this we’re running a kickstarter campaign to raise funds – support the project to get your own set in time for Christmas or choose other rewards.

- Mission Improbable

- StoryMaker

- Animal Match

Animal Match starts out as a puzzle – match up the animal halves to complete the pattern. From there you can make it much more fun : mix the cubes up to invent strange creatures; what would you call them? What would they sound like? How might they move?

Mission Improbable is for role-playing. There are 6 characters: Adventurer, Detective, Scientist, Spy, Storyteller and Superhero, each with 9 tasks. Use them to invent your own games, record your successes in the mission log books or take it to another level by designing your own costumes and props.

StoryMaker incites the telling of fantastical tales : Roll the 3 control cubes to decide how to tell your story, what kind it should be and where to set it. Then use the word cubes as your cue to invent a story on the spot.

Indigenous Public Authoring in Papua New Guinea

October 2, 2013 by Giles Lane · 10 Comments

Towards the end of October 2012 I boarded a flight to Sydney on the first leg of a journey to Papua New Guinea, where I was to give a presentation about public authoring and the Shareables we have created over the past dozen and more years. Through my friend, the anthropologist James Leach, I had been invited to participate in a symposium at the University of Goroka in PNG’s Eastern Highlands to share my thoughts and experiences of using hybrid tools and technologies with different communities to record and share their knowledge, stories and experiences – a process we have called public authoring since developing our Urban Tapestries project back in 2003.

I first got to know James at the University of Cambridge at a symposium he, Lee Wilson and Robin Boast co-organised for CRASSH where I was an invited speaker. We then began collaborating in 2009 when two Reite villagers, Porer Nombo and Pinbin Sisau, came to the UK to participate in a project at the British Museum Ethnography Department. Porer and Pinbin were invited to help identify hundreds of objects from the Rai Coast area of PNG that the BM has in its collections, but about which very little was known. In addition to the audio recording and photography of the objects, James wanted to capture something about the process of encountering and engaging with the objects; he turned to me to explore using the Diffusion Notebooks format we had previously discussed. Over the week or so of Porer and Pinbin’s visit to the BM Ethnographic Store in an east London warehouse several notebooks were made and shared online (these are also browsable on bookleteer and downloadable – Melanesia Project Notebooks). This small project was a personal turning point in several ways and when the opportunity came to visit PNG and to travel to Reite village itself with James I had no hesitation in accepting.

The Saem Majnep Memorial Symposium on Traditional Environmental Knowledge took place from October 31st to 2nd November and featured both local as well as international researchers. James and Porer Nombo presented their book, Reite Plants, as a potential model for sharing local traditional knowledge. I gave a presentation about how we have used the Diffusion eBook format and bookleteer in our work with different communities to record and share their stories, experiences and other things that they value. Prior to visiting PNG James and I had spent a few days discussing and sketching up some possible notebooks to take to Reite village. I had also researched a waterproof paper stock that could both be printed on and written on using universally available pens (such as biro and also Sharpie pens) – which was crucial in the hot and humid climate of PNG where ordinary paper is highly susceptible to mould, damp and disintegration. Taking a small amount of this paper with me, and some test printed waterproof eNotebooks, we made our way via Madang to Reite village.

Once in the village, we realised that the sketches for notebooks that we had planned before were not quite right and that there was a unique opportunity to co-design a simpler approach that reflected local sensitivities to knowledge sharing. Working with Porer and Pinbin again, we devised a new formulation for the wording of the notebooks about the kind of subject matter we would be asking participants to record and share, as well as the provenance of their knowledge. A key ingredient was the informed consent statement that appears on the front cover of each notebook below the space for the participant’s photograph, which was printed and stuck on using a Polaroid PoGo printer, and beneath which each participant wrote their name after reading and agreeing.Having just a limited supply of materials I was able to create 16 notebooks – far less than the number of people who wanted to take part – which were all handmade and written out in the village itself. At a morning meeting, the aims of the project were explained to the participants by Porer and James whilst I took their photos and printed them out to stick on the cover of their notebooks. As a simple pilot, we asked the participants to write about just one thing in their environment about which they had specific knowledge – knowledge that was their’s to share (i.e. not taboo or magical knowledge, hap tok in Tok Pisin). It was important that everyone taking part understood exactly what we were doing and why – that this was intended and an experiment to explore new ways for their community to record what they know and to be able to pass in on to their descendants as well as to share with others.

By the end of our week in the village all 16 notebooks had been returned, filled with stories, drawings and information – the first time I have had a 100% return rate in any participation project! Disassembling each of the notebooks back into flat sheets, I used a cheap portable hand scanner to create our very first digital versions of the notebooks, which were saved as multi-page PDF files for immediate sharing. Once back in our London studio I was able to take more accurate scans on a desktop scanner, but the use of the portable scanner to capture and immediately share (via SD card) digital versions of the notebooks was another useful demonstration of the simplicity of the whole process for sharing in the field without access to mains electricity and the usual infrastructure required for file sharing.

James provided some English translations to the notebooks, which we then incorporated into new versions made and shared on bookleteer – all of which can be browsed online or downloaded as A4 PDFs for making into handmade books in this collection – Reite and Sarangama Notebooks. We also combined the 16 notebooks into three larger bookleteer books grouped together according to subject matter accompanied by a book written by us (in both Tok Pisin and English) browsable or downloadable (as A3 PDFs) in the collection – TEK Pilot 1. Two of these books were recently printed in a small run using bookleteer’s Short Run printing service and sent out to subscribers of the Periodical – read about them here. We are sending handmade versions of all the books and notebooks back to the participants in Reite and Saragama villages, laser printed on another waterproof paper stock for durability.

Our longer terms aims are to expand this process for simple tools and techniques for recording and sharing local traditional cultural and ecological knowledge into a toolkit that could be used in different contexts and situations, and which is, as far as possible, technology agnostic. To do this we plan to return to Reite in 2014 to continue our co-design and collaboration with the villagers there, and to then devise a basic toolkit which can be shared with other people and communities in PNG, then potentially further afield. I would love to hear from others working with traditional or remote communities who’d like to share ideas and perhaps experiment with the process and tools we’ve developed so far.

On the trip to PNG I kept a diary of my experiences for my then 8 year old daughter, which I digitised using bookleteer. It is personal and written with her in mind, yet it is probably the best way to communicate some of the intense experiences I had in the village – with a culture and society that is so very different to my own yet offered so much to me in generosity of welcome, food, gifts and in spirit.

Digital Alchemy

September 25, 2013 by Giles Lane · 17 Comments

Digital Alchemy – transforming data into poetry

“The real nature of matter was unknown to the alchemist: he knew it only in hints. In seeking to explore it he projected the unconscious into the darkness of matter in order to illuminate it.”

Carl Gustav Jung, Psychology and Alchemy

From the late Middle Ages alchemists were frequently depicted as seekers of eternal life and unending riches, a wholly materialist set of objectives that would be facilitated by discovering the philosopher’s stone and being able to transmute lead into gold. However, in the twentieth century, an entirely different interpretation of alchemy gained ascendance due, in large part, to the writings of the Swiss psychotherapist Carl Gustav Jung. Jung interpreted alchemy as a symbolic process that aimed at individuation, the psychological assimilation of opposites whilst retaining their separateness, leading to the psychological (or even spiritual) transformation of the alchemist. The use of symbols and materials in the alchemical process function as archetypes of mythological images that reside within an individual’s unconscious, triggering an internal transformation as they pursue the Work. This likening of alchemy to the esoteric and spiritual traditions of East Asia (such as yoga and meditation) as well as its own Western roots in Hermeticism places it clearly within a framework for reflection, revelation, transfiguration and enlightenment.

In January 2012 a team from Proboscis (Stefan Kueppers and Giles Lane) was invited to collaborate in a critical and creative dialogue with scientists (David Walker and Steffen Reymann) from Philips Research Laboratory in Cambridge as part of Anglia Ruskin University’s Visualise public art programme (commissioned by Andy Robinson of Futurecity with Dipak Mistry of Arts & Business Cambridge). Our collaboration was one of several initiated between artists and industry in Cambridge that were aimed at helping to communicate the benefits that could come from such partnerships. Philips proposed that the theme for our joint dialogue would focus on personal health monitoring. Specifically our colleagues at Philips were interested in exploring new ways to engage nominally healthy people in monitoring their own health and lifestyle as a preventative measure, rather than waiting for a medical condition to arise and then find themselves having to adopt biosensor monitoring as part of a recuperative regime. The aim would be to think of emerging biosensor systems as part of a continual, holistic process of healthy living and wellbeing, rather than just as technological aids for post hoc medical intervention. The problem was that the statistics concerning the use of commercial biosensor products and related smartphone apps demonstrated that the vast majority of users tended to abandon the devices and ignore the data visualisations within weeks of first using them, undermining any potential beneficial impact they could have.

Over the next six months through a series of intense monthly meetings, rapid conceptual development and iterative prototyping we developed an experimental response to the problem. Our project, Lifestreams, proposed a novel way of thinking about the nature of biosensor data and its relationship to how we live our lives. We sought to move beyond the simple graphs and number counting that pervades so much of the ‘quantified self’ meme towards the poetic and numinous; to capture something of the epic in everyday life. Our aim was to transform our relationships to digital data from the ephemeral of screens and interfaces into something that encompassed the tactile and material producing a more subconsciously emotive and emotional experience – an artefact or Lifecharm.

Having developed the basic concept we grappled with the form that such an artefact should take asking ourselves, “What physical form could be mathematically driven by data to create dynamic and interesting shapes that could also communicate some sense of the whole person?”. The answer was to reflect on and revisit nature for archetypal forms and generative principles. In listing the attributes that an artefact generated from information would likely have, we found ourselves describing the growth patterns and expressiveness of shells. The patterns in their growth are determined by the health of the creature (such as a mollusc or snail) making them; what they consume, stress factors and the environmental conditions they exist within. Shells have a near universal fascination so the idea took hold of using contemporary technologies to artificially allow a human to ‘grow’ their own shells from data generated by monitoring their own health and lifestyle patterns.

The lifecharms were created by capturing a range of personal biosensor data types (heart rate, body temperature, blood pressure, step count, sleep pattern, exposure to air pollution) and applying the data to a workflow using algorithms to extend the principles of the helico-spiral with time-based rules. These allow us to ‘grow’ the shell in the Groimp 3D modelling environment producing the initial 3D model surface which we then post-processed using Meshlab software for export as a stereolithographic file. The file can then be sent to a 3D printer to generate the physical artefact in a variety of different materials such as plastic, metals, glass, resin and ceramic. What makes the lifecharms unique is that they are not just parametric or formulaic transmogrifications of the raw data but generative because time as a key element informs the variations in the growth grammar that evolves the shells. Each of the biosensors’ time-series data drives one of the parameters governing the shell’s growth form. The data points are iterated through time intervals and become parameters altering the shell’s growth rules as more data is fed into the model. This gives each shell a non-deterministic morphology somewhat akin to the way a shell would be grown by a living creature.

Our own research into and experiences of using more common screen-based interfaces for visualising biosensor data had left us feeling that they were somehow inadequate. Their frankly mechanistic approach to relaying the data back to the user seemed to lack the kind of poetry that would allow someone to weave the process into the daily narrative that people construct about themselves. Unlike data visualisations the lifecharms are generated through a process of non-deterministic spatial data transformation. It does not confine them to such an instrumental purpose as merely relaying the original data back to us as information in a simplified and easy to comprehend manner. Instead, they are embodiments of the data, transformed from the abstract and ephemeral into the concrete and present. They establish the potential for uncommon insights to be perceived into the health conditions and lifestyle patterns in which the data was collected. Such insights are prompted by tactile and intuitive reflection.

Over the past decade Proboscis has been exploring tactile interfaces and tangible souvenirs as a key part of our research into the way people create and share knowledge, stories and experiences – what we call public authoring. An element of the handmade often features in the outputs we design, but here the imprint of the person about whom the data being shared is directly embodied in the object itself. A Lifecharm shell synthesises the intrinsic qualities of the data within its morphology; visualisations, on the other hand, make extrinsic interpretations of such data. It is, at one and the same time, both an informational object – representing a state gleaned from sensor data – and also a philosophical thing triggering intuitive reflection. It unites different traditions of investigation and meaning making: the scientific and the mythic, or magical, both being and becoming. However, a lifecharm is neither an icon nor iconic, nor yet an implement or tool – it embodies a state without representing it banally. What it exemplifies is not knowledge in the form of a ‘transactable’ commodity or product but a path to knowing that arises from an ongoing process of continuous interaction with and intervention within everyday habits, in this case practiced daily through touch.

“Magic in its earliest form is often referred to as “the art”. I believe this is completely literal. I believe that magic is art and that art, whether it be writing, music, sculpture, or any other form is literally magic. Art is, like magic, the science of manipulating symbols, words, or images, to achieve changes in consciousness.”

Alan Moore

The Lifecharms are not rational, functional objects, they are magical, irrational, indeed talismanic things by which, through tactile familiarity, we may come into knowledge or understanding by way of revelation. Like poetry, which is much more than the sum of words and their arrangement on a page, they are more than the sum of the data that drives their growth parameters.

Carrying a lifecharm and touching it everyday, both consciously and even as a displacement activity, causes you to develop a relationship with it over time. You become familiar with its materiality – the feel of the shape in your hand; the weight of the material it is made of, the textures of its surface. None of these reveal the patterns in the data that generated it directly, however this is precisely the point at which the lifecharm begins to operate in a mythic or magical capacity – as a performance of patterns of being and of behaviour embodied and reified into a talisman. Its magical power could be defined as the potential for revelation that it holds for you to come into an uncommon insight by handling it over time. In this way you might come to perceive new possibilities for change and adaptation in your own patterns and behaviours – triggering your own process of subjective transformation. The lifecharm is thus not just a thing of being but a thing of becoming. Their role in the personal narratives we construct around our daily lives is revealed as much through our continued interaction with them as by their thingness.

Like poetry, the lifecharms are also diachronic – meaning that we can experience and relate to them across time, whilst the meaning or data they embody is fixed in time (i.e. the shape of the shell or the words of the poem do not change). Dynamic data visualisations may often be synchronous – i.e. driven by live or recent data streams – but the way we experience and relate to them is likely to be mediated (through devices such as smartphones, tablets or computers) and determined by our behaviours and patterns of using those devices they are mediated through. This makes the lifecharms intrinsically different to screen-based visualisations of data. The information that we may glean from them is less to do with an instrumental replay in visual form and much more to do with how we begin to learn about the patterns they embody through a growing tactile familiarity with their physical form. This difference becomes an opportunity to augment our means of understanding the phenomena recorded in the biosensor data – an opportunity to explore meaning making through a relationship to complexity and intersubjectivity.

About six months after our initial three generations of shells were created and 3D fabbed I came into my own uncommon insight – that the shells were in fact, tactile poems. This happened partly as a result of my stay in Reite village in Papua New Guinea with anthropologist Professor James Leach (University of Western Australia/CNRS) during November 2012 and our conversations since, as well as those I have had about my experiences there with poet Hazem Tagiuri (a Proboscis associate). The villagers of Reite lead a traditional ‘kastom’ lifestyle in the jungle with a fairly minimal exposure to a ‘modern’ existence predicated on patterns of consumption and mediated sociality. (Although the modern world of industrially produced goods and telecommunications is slowly but surely encroaching and making an impact on their lives and culture). Reite people were traditionally non-literate and remain highly skilled makers, carving and weaving many of the things they use. Touch is a powerful sense through which they acquire information about their world, as indeed it could also be said to be with highly skilled artisans and craftspeople of our own society. However, the incredible sense of presentness in everyday Reite life and the intensity with which they conduct continuous social relations is vastly unlike our Western culture of discontinuous being, mediated as it is through patterns of dislocation, telecommunication and distraction. I felt that their physical knowledge of materials connects at a deeper level and is more attuned to detail and granularity than ours. Looking at our own society and culture, such physical, traditional knowledge has been debased as a lower form of skill and social standing – for instance in the negative way manual labour is contrasted with intellectual work, or how craft is ‘lesser’ than Art – for centuries.

Since returning from PNG my conversations with James have often focused on this intensity and presentness – a kind of radical continuity with being that life in the village feels like. This intensity has also been the subject of my many attempts to describe what life in the village feels like to others. An enduring memory I have, and which I described to Hazem, was watching a man ‘conjure’ fire from cold sticks in a firepit without using any form of tinder, or ember or fire-lighting materials. What seemed like magic or an illusion was an everyday demonstration of the uncanny power and knowledge this man possessed. He knew just how to feel for residual warmth within the sticks and arrange them in just the right way that would amplify the heat enough to stimulate combustion, a skill and power I have neither witnessed nor even previously heard of. The poem Hazem subsequently wrote helped me to connect the lifecharm’s talismanic nature to poetry. It helped kindle the spark of revelation that, like the way we come to know a thing through poetry, so the kind of knowing that resides within our hands and sense of touch is not just symbolic knowledge, but actual; that we may truly come to know something through touch alone. And that, like in poetry, the precise, elusive moment in which we come into the knowledge that the lifecharm offers us remains on the edge of conscious thought; a sensation we intuitively call revelation. Perhaps such a thing might also be described as the Work of digital alchemy.

Giles Lane

Loch Ard, Scotland August 2013

This essay was first published in Tasting Notes, a book accompanying the exhibition, This New Nostalgia, curated and published by InspireConspireRetire, September 2013.

Neighbourhood Ideas Exchange Toolkit

September 16, 2013 by Giles Lane · 28 Comments

Last year we collaborated with the Possible Futures Lab of the Information Security Group at Royal Holloway University of London to assist local people in Pallion, Sunderland develop a way to come together and help each other map out the skills, knowledges, resources and capabilities for responding to and effecting change in their community. The outcome of this was the establishment of a regular group of people working out of the community centre Pallion Action Group. As part of our work with them we co-designed a series of simple ‘tools’ that could be used to help them do things like identify problem and solutions and share them online confidently and safely.

The tools use very simple paper-based formats – wall posters, postcards and notebooks – that can either be printed on standard home/office printers or cheaply printed at larger sizes at local copy shops. The notebooks are created with bookleteer and can be downloaded direct : http://bookleteer.com/collection.html?id=9

To make these tools available to anyone for use in their own communities, we have now designed generic versions and collected them into a Neighbourhood Ideas Exchange Toolkit. The toolkit is free to download and everything in it is free to adopt and adapt under a Creative Commons Attribution Non-commercial Share-Alike license.

Download the Neighbourhood Ideas Exchange Toolkit (zipped archive 48Mb)

We would love to hear of anyone’s experiences using or adapting these tools for their own purposes and keen to hear of suggestions for improvements or additions to the toolkit. One of the items we feel is currently missing is some form of simple self-evaluation tool for communities to use to determine how successful (or not) they are in achieving their aims and objectives. We are also working on a special set of StoryCubes designed to help both organisers and communities work through common issues and to devise solutions and activities that help them set up their own Neighbourhood Ideas Exchange.

Where possible (time and resources permitting) we are willing to develop new or customised versions of specific tools, such as the notebooks or worksheets. Please get in touch with us to discuss your ideas or suggestions.

Neighbourhood Ideas Exchange by Proboscis is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

Sale of works

June 10, 2013 by aliceangus · 5 Comments

During our open days Friday 21st June and Saturday 22nd June between 12noon and 8pm we will also be selling some work from recent years including framed and unframed works on paper and textiles as well as publications including:

Works on paper from the Storyweir series Things I Have Found, Learned and Imagined on Burton Beach; the series In Good Heart , Pinning Our Hopes, and the original drawings for 100 Views of Worthing Pier Tall Tales Ghosts and Imaginings and As It Comes as well as other works on paper and textiles. You can see some more of some of the series of the drawings here

‘Hidden Families’ at Conference on Human Factors in Computing 2013

May 1, 2013 by aliceangus · 5 Comments

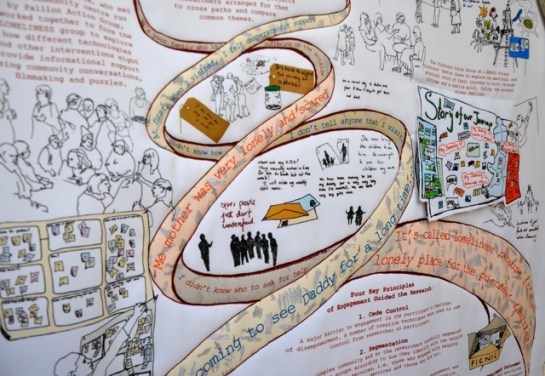

As part of our project Hidden Families with Lizzie Coles-Kemp (from the Information Security Group at Royal Holloway University of London). Alice illustrated, digitally printed and created a handmade quilted textile ‘poster’ about the wider project for the 2013 ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing.

Hidden Families StoryCubes

March 25, 2013 by aliceangus · 2 Comments

“The visitors who told their stories are very proud of the work and the fact that they can see their work put to good use.” Cath Chesterton NEPACS

We were recently asked to create a set of 8 StoryCubes for Hidden Families (part of Royal Holloway University of London’s Families Disconnected by Prison project), to be used by Royal Holloway and partners such as Action for Prisoners Families, NEPACS and in training, talking about and raising awareness of the issues faced by families with a relative in prison.

We selected 48 of the images, originally created for the Hidden Families quilt, around the six key themes that had emerged – family, journey, time, finance, loneliness and support. Using a combination of participants’ photos, words and sketches with my illustrations, we created a block of 8 cubes that brings together some of people’s memories, comments and experiences.

Lizzie Coles-Kemp project lead said; “The focus of this project was to create a call to action by collecting the voices of families separated by prison and using different techniques to present the collective narrative. StoryCubes help us to develop the call to action by making the collective narrative interactive and providing another means for adding to and developing the story of this particular community. They make interactive and tactile objects from the textile quilt which are even more accessible to families, policy makers, practitioners and academics alike.”

NEPACS and Action for Prisoners Families will be using the cubes at training events and conferences, raising awareness of the impact of prison sentences on families.

View the whole Collection of 8 StoryCubes

Lifestreams : Tactile Poetry

March 21, 2013 by Giles Lane · 14 Comments

Since early December last year I’ve been carrying around one of the Lifecharm shells with me every day. It was generated from personal biosensor data gleaned not just from myself but from two other studio members last summer when we were capturing a range of experimental data sets to generate prototypes with. Using the data, Stefan generated this particular lifecharm as part of our third iteration of prototypes in late July. This shell was one of several that we later chose to have 3D printed in different materials at Shapeways – this one in sterling silver, the others in glass, ceramic, resin and steel.

I have been carrying it around to see how I feel about it, what it means to me and how I weave it into my everyday life. Our original concept for the lifecharms was that they might trigger an entirely novel way of developing meaningful relationships to the kinds of personal health data gathered by sensors (such as Fitbit, Fuelband etc) that people are now adopting as part of the ‘quantified self’ meme. Our colleagues at Philips Research, David & Steffen, told us that the statistics of use of these kinds of sensors by healthy people tended towards abandonment after just a few months as interest and engagement fades. Their interest was in exploring motivations that might make self-monitoring of wellbeing and healthy lifestyle a thing someone would choose to do before they discovered a health issue that required monitoring.

Our approach to this was to think about the way such sensor data is relayed back to users – most commonly in the form of screen-based visualisations. We wondered if perhaps these simply aren’t arresting enough to weave themselves into the narratives of everyday life that people construct for themselves. I’ve long been interested in touch as a form of knowing and sharing, and Proboscis have been exploring physical outputs from digital experiences for many years (such as tangible souvenirs) so we started out by thinking about how we might embody the data in a physical form that could be carried around and used like a charm or talisman. Stefan has written previously about our research methods and the journey that led us to devise the lifecharm and its inspiration from nature. His Lifestreams film also explains the various technical processes we adopted and adapted to create the results.

What’s so special about these ‘data objects’?

Unlike data visualisations the lifecharms are generated through a process of data transformation that does not confine them to an instrumental purpose such as relaying the original data back to us as information in a simplified and easy to comprehend manner. Instead, they are embodiments of the data, transformed from the abstract and ephemeral into the concrete and present. They establish the potential for uncommon insights to be perceived into the conditions from which the data was collected (i.e. someone’s health and lifestyle patterns), prompted through a process of tactile and intuitive reflection.

A Lifecharm shell synthesises the intrinsic qualities of the data within its morphology (visualisations, on the other hand, make extrinsic interpretations of such data). It is, at one and the same time, both an informational object – representing a state gleaned from sensor data – and also a philosophical thing triggering intuitive reflection. It unites different traditions of investigation and meaning making: the scientific and the mythic, or magical, both ‘being’ and ‘becoming’. However, a lifecharm is neither an ‘icon’ (nor iconic) nor an ‘implement’ (tool) – it embodies a state without representing it banally. What it exemplifies is not knowledge in the form of a ‘transactable’ commodity or product but a path to knowing that arises from an ongoing process of continuous interaction with and intervention within everyday habits, in this case practiced daily through touch.

Tactile Poetry?

The Lifecharms are not rational, functional objects, they are magical, irrational, indeed talismanic things by which, through tactile familiarity we may come into knowledge or understanding by way of revelation. Like poetry, which is much more than the sum of words and their arrangement on a page, they are more than the sum of the data that drives their growth parameters.

Carrying a lifecharm and touching it everyday, both consciously and even as a displacement activity, causes you to develop a relationship with it over time. You become familiar with its materiality – the feel of the shape in your hand; the weight of the material it is made of, the textures of its surface. None of these reveal the patterns in the data that generated it directly, however this is precisely the point at which the lifecharm begins to operate in a mythic or magical capacity – as a performance of patterns of being and behaviour embodied and reified into a talisman. Its ‘magical power’ could be defined as the potential for revelation that it holds for you to come into an uncommon insight by handling it over time. In this way you might come to perceive new possibilities for change and adaptation in your own patterns and behaviours – triggering your own process of subjective transformation. The lifecharm is thus not just a thing of being but an thing of becoming.

Like poetry, the lifecharms are also diachronic – we can experience and relate to them across time, whilst the meaning or data they embody is fixed in time (i.e. the shape of the shell or the words of the poem do not change). Dynamic data visualisations may often be synchronous – i.e. driven by live or recent data streams – but the way we experience and relate to them is more likely to be mediated (through devices such as smartphones, tablets or computers) and determined by our behaviours and patterns of using the devices they are mediated through. This makes the lifecharms intrinsically different to screen-based visualisations of data. The information that we may glean from them is less to do with an instrumental replay in visual form, and much more to do with how we begin to learn about the patterns they embody through a growing familiarity with their physical form. This difference becomes an opportunity to augment our means of understanding the phenomena recorded in the bio sensor data – an opportunity to explore meaning making through a relationship to complexity and intersubjectivity.

I came to my own uncommon insight – that the shells were in fact, tactile poems – partly as a result of my stay in Reite village in Papua New Guinea and the conversations I have had since with anthropologist James Leach, and also with poet Hazem Tagiuri. The villagers of Reite lead a traditional ‘kastom’ lifestyle in the jungle with a fairly minimal exposure to a ‘modern’ existence predicated on patterns of consumption and mediated sociality. (Although the modern world of industrially produced goods and telecommunications is slowly but surely encroaching and making an impact on their lives and culture). They were traditionally a non-literate people and remain highly skilled makers, carving and weaving many of the things they use. Touch is a powerful sense through which they acquire information, as it could be said to be with highly skilled artisans and craftspeople of our own society. But coupled with the incredible sense of presentness in everyday Reite life and the intensity with which they conduct social relations that is so unlike our own society of discontinuous being, I felt that their physical knowledge of materials connects at a deeper level and is more attuned to detail and granularity; whereas in our own western culture it has been debased as a lower form of skill and social standing – such as the negative way manual labour is contrasted with intellectual labour, or how craft is ‘lesser’ than art.

Since returning from PNG my conversations with James have often turned on this intensity and presentness – the form of radical continuity with being that life in the village feels like. I have, in turn, attempted to convey my experiences to friends, to describe how utterly different I felt whilst in the village. During the course of one conversation with Hazem I described watching a man ‘conjure’ fire from cold sticks in a firepit without using any form of tinder, ember or fire-lighting materials. What seemed like magic was a demonstration of the uncanny power and knowledge this man had in knowing how to feel for residual warmth within the sticks, and arrange them in just the right way that would amplify the heat enough to stimulate combustion. A skill and power I have not witnessed nor even heard of before. Hazem wrote a poem about my description of this act which he sent me as I was grappling with writing about the lifecharms and what they are. His poem helped me to connect the lifecharm’s talismanic nature to poetry. It helped kindle the spark of revelation that, like the way we come to know a thing through poetry, so the kind of knowing that resides within our hands and sense of touch is not just symbolic knowledge, but practical; that we may truly come to know something through touch alone. And that, like in poetry, the precise, elusive moment in which we come into the knowledge that the lifecharm offers us remains on the edge of conscious thought; a sensation we intuitively call revelation.

Invoking Fire by Hazem Tagiuri

We talk of his time in the jungle.

He describes one marvel in particular:

how a fire was conjured from cold sticks,

as if heat swelled in their fingertips.

No tinder, hot coals; embers a day dead.

“It’s not that it seems like magic, it simply is.

Their magic. These are not illusions.”

No sleight of hand. Smoke, but no mirrors.

What we mimic through tools,

these men of power can summon,

with quiet majesty. No incantations;

they save their breath for the flames.

New Threads

January 31, 2013 by aliceangus · Comments Off on New Threads

A delivery of digitally printed fabric arrived this morning with the work for the Hidden Families project and for my mermaids and monsters work. I’ll be spending the next few days sewing up the quilts for Hidden Families partners.

The other fabric that arrived is part of new textile and embroidered work inspired by the traditional knowledge, memories and myths of the sea and water that have come up in Storyweir and Tall Tales Ghosts and Imaginings, In Good Heart and Sutton Grapevine.

Hidden Families

January 16, 2013 by aliceangus · 2 Comments

In the last few months I’ve been working on Hidden Families, a project with families with someone in prison. The project, run by by Lizzie Coles Kemp of the Information Security Group at Royal Holloway University of London, was trying to find out how to improve the way information is made available to families, because people sometimes don’t or can’t engage with support services. The hardships families experience are diverse;- travel, costs of visiting, the huge distances to visit,the stress of uncertain weather and travel conditions that might cause someone to be late and miss their visit, bringing children, access to pension, welfare and benefits advice, sentence planning, prisoner safety and welfare, being stigmatised and outcast, and not expecting help or having the ability to improve the situation.

The project has several facets and I was involved in working with Action for Prisoners Families, NEPACS (who provide support services for families separated by prison), performer Freya Stang and visitors to a visitors’ center in a Category A prison.

Action for Prisoners’ Families (APF),

works for the benefit of prisoners’ and offenders’ families by representing the views of families and those who work with them and by promoting effective work with families…

A prison or community sentence damages family life.

NEPACS builds bridges between prisoners, families and communities that they will return to, they

believe that investment must be made in resettlement and rehabilitation to ensure that there are fewer crime victims in the future, and less prospect of family life being disrupted and possibly destroyed by a prison sentence… After all, the families haven’t committed the crime, but they, especially the children, are greatly affected by the punishment

Lizzie’s approach to working with people differs from typical academic studies. Rather than only surveying or asking questions of a community she collaborates with groups to create projects, workshops and events that are independently of value to that group, rather than just to fulfill research ends, she often works with artists, writers and performers to support partners and participants in articulating ideas.

The project partners and visitors contributed to booklets, postcards, conversations and a wall collage gathering experiences of the practical, technical and emotional issues people face. I brought together the stories, experiences and sketches, with a series of sketches I made, into a digitally printed textile hanging based on the idea of a patchwork quilt for the NEPACS Visitors’ Centre. Participants expressed a wish to produce a version that could hang in the Chapel and Action For Prisoners Families have versions which they will using for their training, education and work raising awareness of the hidden issues families face.

New Lifecharm Shells

December 12, 2012 by Giles Lane · 2 Comments

Our colleague at Philips R&D, David Walker, was kind enough to have some more shells 3D printed in metal for a small experiment we’re planning to run in the new year. Here are some photos he’s taken of them.